Jake Gyllenhaal is losing it. As with so many of his films — Demolition, Southpaw and Nightcrawler, to name a few — the actor’s latest, the unconventional crime thriller The Guilty, finds him yet again portraying a troubled man, beaten down and about to crack up. Joe Baylor is an LAPD cop relegated to working at the 911 call center as the result of misconduct some eight months before. Surly and apathetic, Joe answers the nightshift calls, ranging from drunken mishaps to carjackings, with a disgust he doesn’t care to contain. He longs to return to the streets. The night turns, however, when Joe fields a call from a woman (voiced by Riley Keough) who’s been abducted and is being held in a white van.

Directed by Antoine Fuqua, The Guilty (a remake of a 2018 Danish film) is not your prototypical crime thriller, owing to Nic Pizzolatto’s highly literary script. Pizzolatto, of True Detective fame, is at his best when writing dialogue: think of the masterly exchanges between Rust and Marty in the first season of that series. This a good thing, because nearly all the major action in The Guilty occurs offscreen while Gyllenhaal’s Joe screams into his headset in the probably futile hope of saving Emily from her kidnapper. The Guilty is clearly a showcase for Gyllenhaal, who carries the film, keeping it from going off the rails and crashing into melodramatic terrain, which it almost does.

Still, much of the pleasure one derives from a film like The Guilty has less to do with the plot and more to do with seeing how its writer attempts to elevate it, through literary devices, from your standard crime thriller to highbrow art. With a runtime of only ninety minutes at his disposal, Fuqua, on occasion, struggles to unify Pizzolatto’s many literary flourishes, including an ominous fire burning at the edge of Los Angeles County that serves as a ham-handed metaphor for Joe’s worsening psychological state. Fuqua, to his credit, keeps these scenes to a minimum and trains his eye on the film’s true emotional core: the specter of Joe’s undisclosed misconduct that haunts him and has left him on 911 duty.

The only literary trope in the film that works seamlessly situates Joe only a few hours out from the most important morning of his life — the court hearing that will determine his fate. Joe’s reckoning becomes more imminent with each passing second, and as Gyllenhaal dials up his trademark “crazy-man-on-the-brink” moves in accordance with the ticking of the clock, Fuqua clears away what remains of Pizzolatto’s literary roughage and focuses on Joe’s embittered countenance.

After calling Emily’s house and finding out from her six-year-old daughter that Emily has been taken by her ex-husband, Henry, Joe steps into high gear, breaking protocol in the process. He ignores incoming calls and reaches out to his former partner and sergeant at the LAPD to assist him in saving Emily himself. The exchanges between Joe and Emily, which make up the bulk of the dialogue in The Guilty, create a kinship between the disgruntled cop and the young woman whose brokenness mirrors his. In a strangely touching scene, bordering on the erotic, Emily tells Joe about her favorite place, the aquarium, and how she’d love to meet him there after their ordeal is over. We get the sense that all is not well with Emily (besides her having just been kidnapped and thrown into a van). On cue, at the start of the third act, we’re hit with the twist: she confesses that Oliver, her baby, “had snakes in his stomach” and that she proceeded to “take them out.” Emily, it turns out, has not been maliciously kidnapped by Henry, but is being taken to a psychiatric hospital. To reveal the twist is not to spoil the film because the important question at the core of The Guilty has nothing to do with the kidnapping and everything to do with Joe’s tortured need for absolution.

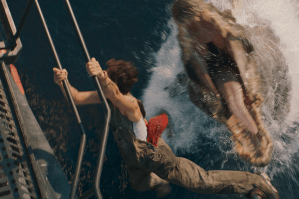

Fuqua and Pizzolatto have made careers mining the same thematic terrain, of broken men and masculine dysfunction, so it is no surprise that as The Guilty reaches its logical conclusion, Joe finally releases the rage and confronts himself. Emily, having escaped the van after hitting Henry with a brick, finds herself on the edge of an LA freeway, threatening to “join Oliver.” Joe confesses his great act of violence, the reason for his being investigated. Like much of The Guilty, the scene nearly tips over into the farcical, but Gyllenhaal’s commitment to the material saves the scene, as well as the film. You can’t say he’s guilty of phoning it in.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2022 World edition.