The role of Hamlet is, Max Beerbohm famously wrote, ‘a hoop through which every eminent actor must, sooner or later, jump’. In this book, and in its online supplement, Jonathan Croall charts the flight through that hoop of pretty well all of the ‘eminent actors’ — male and female, young and not so young, white and black — who have taken the leap in British performances, from Michael Redgrave with the Old Vic company in 1950 to Andrew Scott at the Almeida in 2017.

The trajectory of the actor’s flight is of course different in every production. No play text is complete until it is performed, and every time it is performed it takes on a new identity, determined by factors such as the personalities of the actors, the place of performance, the interpretative ideas of the director, and even the weather — in a brief account of Hamlets at Elsinore, Croall records John Gielgud’s description of a performance there as resembling ‘extracts from the Lyceum production with wind and rain accompaniments’.

Moreover, even on the page Hamlet is the most fluid of texts. It’s come down to us in three versions: one corrupt (the ‘bad quarto’ of 1603) ; another printed as Shakespeare first completed it (the ‘good quarto’ of 1604–5); and a third with changes, omissions and additions made for performance, some of them of a topical and local nature (the First Folio text of 1623). If you try, as the 18th-century actor David Garrick put it, to ‘lose no drop of that immortal man’, you end up with a text of over 4,000 lines — the ‘eternity version’, as it has come to be known — rivalling in performance length the longest of Wagner’s operas. Most directors, like most editors, draw variously on the good quarto and the Folio.

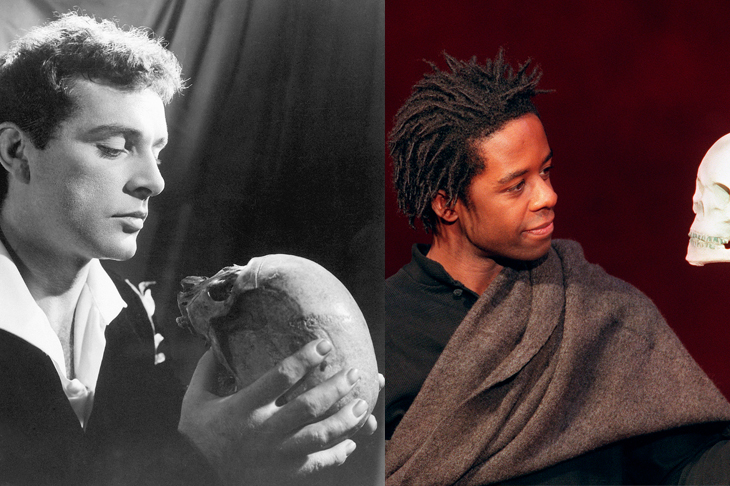

Directing the young David Warner for the Royal Shakespeare Company in his ‘student prince’ version of 1965, Peter Hall omitted some 730 lines. Ophelia was played by Glenda Jackson — it’s fascinating, especially in view of her recent triumph as King Lear, to learn that she later turned down the chance of playing Hamlet. But when in 1975 Hall came to direct Albert Finney for the National Theatre at the Old Vic, he regretted this as a barbarous decision, regarding cutting as the result of ‘some preconceived theory for the production, or because we simply can’t make the passage work’. So, says Croall, ‘he used the unabridged second quarto’ — which still lacks some 70 lines unique to the Folio. Peter Brook, on the other hand, directing Adrian Lester in 2001, was confident that he could ‘take out of this long, sprawling melodrama those elements which come straight to the heart of everyone’s interest’ and find ‘a very pure, essential myth’, which ‘speaks to us directly today without any decoration’.

The bulk of Croall’s book is made up of relatively brief (two- or three-page) run-downs of individual productions, focusing on the central performer, while also sketching the director’s approach, the contributions of actors in subsidiary roles and the critical reaction. For more recent productions, Croall draws on interviews with actors and directors; and the penultimate section reprints in revised form his booklet written for the National Theatre on John Caird’s 2000 production, starring Simon Russell Beale.

Some directors have used bizarre rehearsal techniques. Buzz Goodbody (who committed suicide just as her production, starring Ben Kingsley, opened at The Other Place in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1975) required her unfortunate Ophelia to be wrapped in a shroud and to undergo a mock funeral in the grounds of Holy Trinity Church. Mark Rylance similarly ‘underwent a burial ritual in a hole dug by the grave-diggers’. And the emotional demands of the role have taken a heavy toll on some of its interpreters. Nicol Williamson frequently walked off stage mid-speech; ‘people even bought tickets in the hope of seeing a display of temperament.’ And famously Daniel Day-Lewis, in the middle of Hamlet’s scene with the ghost, ‘suddenly walked off stage, and told the stage manager he couldn’t continue’, provoking rumours that he believed he had seen his own father’s ghost.

Other performers, happily, have not merely survived the ordeal unscathed, but enjoyed and profited from it. ‘The part just adapts itself to you; it’s one of the most hospitable an actor can play,’ says Simon Russell Beale. ‘It says “come and get me, I’ve got everything here, just pick what you want”.’

The roll-call continues. Since the book was completed we have had Michelle Terry’s touchingly witty Hamlet at the Globe, not to speak of the marvellous opera by Brett Dean, whose libretto draws on all three of the early texts. The play goes on giving, interacting inexhaustibly with both its interpreters and its audiences.