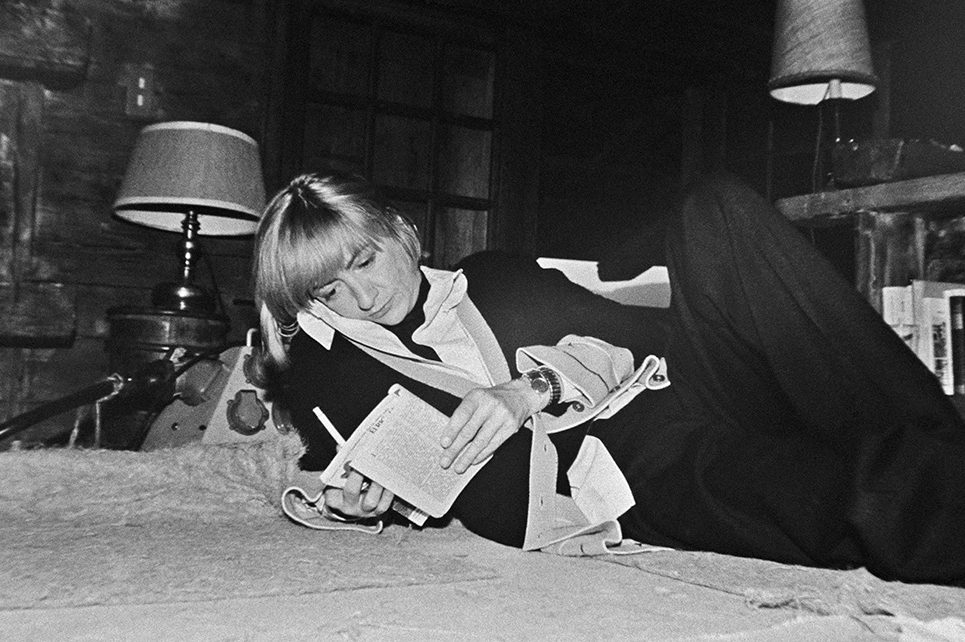

Do not be alarmed. You have not suffered a blow to the head. Françoise Sagan, the author of the 1954 phenomenon Bonjour Tristesse (published when she was eighteen; 2 million copies sold), is indeed no longer with us. She died in 2004, aged sixty-nine. Yet here is her brand new novel, recovered by her son Denis Westhoff from the mass — and presumably mess — of her papers. Perhaps better described as an unfinished story, there’s a romantic charm, innocence and otherworldliness to this book of a kind unlikely to be found in a contemporary novel. But it’s also an uncomfortable read in parts, no matter how ironic the text is supposed to be.

On the plus side, the balance of characters, plot and tone has similarities to Bonjour Tristesse (itself a perfectly formed novella and perhaps the ultimate summer read). There is no clear hero or anti-hero. There is an atmosphere of languid torpor in a milieu of idle, wealthy people who are supremely conscious of their aesthetic and romantic status. And everything centers around a car crash. (Sagan’s own life featured multiple dramatic car crashes, although she eventually died from a pulmonary embolism.)

Less appealingly, though, this is not so much about the four corners of the heart as about the three sides of a rather unfortunate love triangle composed of a son, a father and a mother-in-law. Ludovic Cresson, the heir to a vegetable fortune (the Cresson family are literally “cress” millionaires), is three years into his recovery from a car accident seemingly caused by his wife Marie-Laure. He has finally come home after a lengthy stay in hospital. Marie-Laure angrily refuses to accept that Ludovic has returned to his previous self and insists that he is broken after his time in rehab. Enter Fanny, Marie-Laure’s mother, who is initially intent on helping her daughter and son-in-law patch up their marriage, but — surprise! — ends up falling in love with Ludovic herself. Awkward.

Meanwhile, Ludovic’s father Henri, a ridiculously preening man who detests his wife, also — surprise! — sets his cap at Fanny. Even more awkward. As for Ludovic’s health, Henri is determined to prove that his son is sound of body and mind and enlists various local prostitute friends to aid his recovery. This is what I mean by “uncomfortable.” You expect prostitutes in Guy de Maupassant or Colette, but the episode feels both broad-brush and anachronistic — although that’s hard to tell, as it’s neither clear when this text was written or indeed when the events are set. But to be fair, the sex workers are the nicest people in the book.

Amid arguments about Chanel skirts, rounds of golf and the arrival of various dubious characters, the ménage-à-trois builds to a set piece of a grand party, where presumably there will be a showdown between all these characters. Yet… we never get there, because the work is unfinished. So we can only guess whether Fanny ends up with the son, the father, the butler (did I mention the butler?) or just decides to leave them all to their own French devices with the ladies of the night. It’s definitely one for fans of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, the 1972 Buñuel film starring Catherine Deneuve.

Despite the abrupt non-ending, the strangeness of the story and the debatable wisdom of publishing unfinished works generally, the book is a curiously pleasing reminder of what a one-off Françoise Sagan was. She is never boring, and always a little unhinged. You have to disagree with what she wrote in her own obituary: “Her death, after a life and a body of work that were equally pleasant and botched, was a scandal only for herself.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.