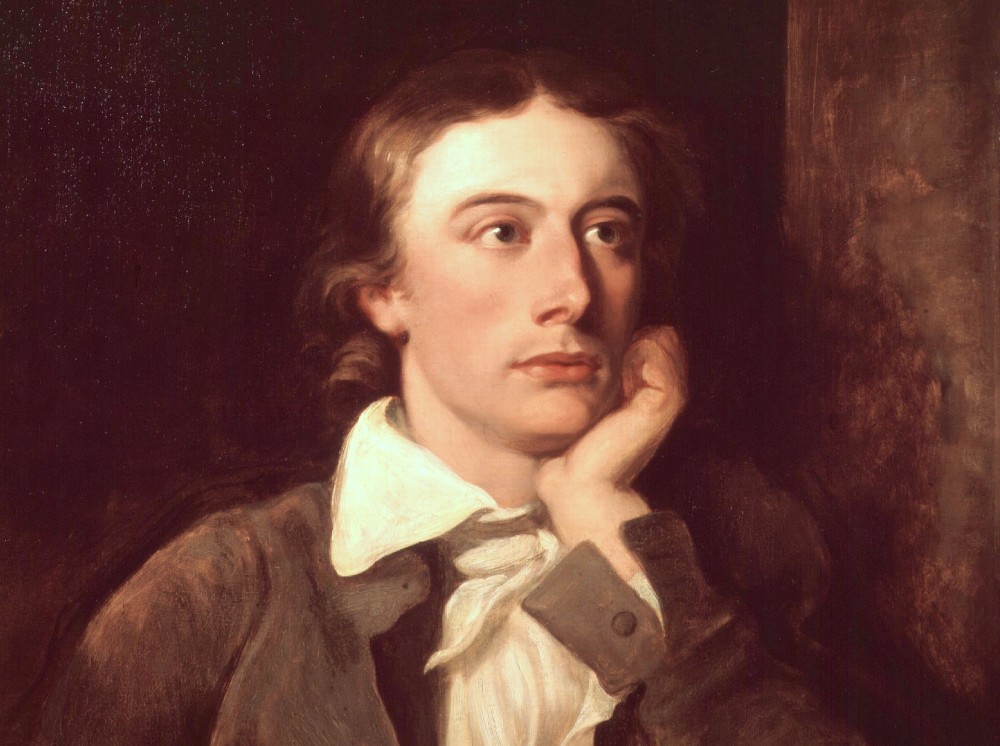

When John Keats wrote “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” he had just returned from a long evening at the home of a childhood friend, Charles Cowden Clarke. Charles Clarke was the son of the headmaster of Clarke’s Academy, where Keats had gone to school. A week earlier, Clarke had introduced Keats to one of his heroes, Leigh Hunt, editor of the independent Examiner (Hunt was imprisoned for two years for printing that the Prince Regent was “a fat Adonis at forty”), friend of William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb, and literary kingmaker. Hunt despised what he viewed as the overly ornate poetry of Alexander Pope, preferring instead Chaucer’s earthy Old English and the directness of Shakespeare and Milton.

On the evening of October 25, 1816, after dinner and wine, Keats and Clarke pored over a borrowed edition of George Chapman’s 1616 translation, The Whole Works of Homer. Keats walked home (across the Thames) in the early hours of the morning and wrote “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer.” He sent the poem in the morning post to Clarke. It arrived by breakfast.

In the poem, Keats praises Chapman’s “loud and bold” translation (the obvious contrast here is Pope), which not only brought the poem to life (Keats did not know Greek, for which he would be mocked when the poem was published) but the world around him, too. “Then felt I,” Keats writes, “like some watcher of the skies / When a new planet swims into his ken.”

These details come from Lucasta Miller’s Keats: A Brief Life in Nine Poems and One Epitaph. There have been dozens of biographies of Keats and about as many critical introductions as you would care to read, but Miller’s Keats is different in a couple of useful ways. The nine chapters are keyed to the poems, which are roughly sequential, starting with “Chapman’s Homer” in 1816 and ending with “Bright star!” composed in 1820. The volume ends with a short note on Keats’s epitaph on his gravestone in Rome, where he died in 1821. Each poem is quoted in full at the beginning of the chapter, followed by Miller’s biographical and contextual commentary.

Miller’s commentary is entirely free from jargon and the concerns of contemporary political discourse — two things that have ruined many otherwise good books. She makes a small misstep in referring to Hunt’s circle as “the heart of avant-garde literary London,” but this is the only anachronism in the whole book — an accomplishment that’s today worthy of recognition!

The biographical portrait of Keats that emerges is of a young man of immense talent, ambition, and energy, whose life was marred by tragedy and then cut short. This won’t be new for readers familiar with Keats’s life. But what is interesting is how the format of the book allows Miller to relate relevant events in Keats’s life directly to the poems. She reads “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” at least to a degree, in light of Keats’s abandonment by his mother when he was eight shortly after his father’s bizarre death (he fell of his horse a short distance from home even though he was likely an expert rider). When Keats was five, Miller tells us, he “stopped his mother from going out by shutting the door and threatening her… with ‘a naked sword.’” His mother apparently burst into tears and had to be rescued by passersby. Without reading too much into every event in Keats’s life (certainly a danger in a book like this), Miller effectively relates this to the sense of abandonment captured in the poem.

This isn’t a book for those looking for an exhaustive portrait of the poet. Keats’s relationship to Wordsworth gets condensed into a single meeting and a few lines of dialogue, and his other relationships are treated more briefly than in a straight biography — this is A Brief Life after all.

But it is for those hoping to learn something about his poetry and its context. Some of his most anthologized poems are included — “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” “Ode to a Nightingale,” “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” Miller discusses “Ode on Melancholy,” “Ode to Psyche,” and “Poetry and Sleep” in passing, but not in stand-alone chapters. Some readers may find this unfortunate, but I found that combining Keats’s “hits” with poems (or excerpts) that are less well known gave the book balance.

Keats wrote most of his best poems over two years, between 1818 and 1819, shortly before he died at 25. His work still stuns today, even though he only had a secondary education and came to poetry late in life. In addition to his odes and sonnets, he translated the Aeneid (he may not have completed it) and wrote the 4,000-word Endymion while also taking medical training to be a surgeon.

How did Keats do so much, so well, in such a short period of time? Who knows? But if you are looking for a reliable and readable introduction to his life and work, look no further than Miller’s Keats.