Geography, climate, economics and nationalism are often seen as decisive forces in history. In this dynamic, original and convincing book Dominic Lieven considers emperors and their dynasties as motors of events.

Defying constrictions of time and space, ranging from Sargon of Akkad, the ruler of what is now northern Iraq (r. 2334-2279 BC), to the Emperor Hirohito of Japan (r. 1926-89), he believes that “for millennia, hereditary sacred monarchy had been the most desirable and successful form of polity on Earth.” (Inhabitants of city states, from Athens to Venice, might not have agreed.) Emperors could create and extend states more easily than impersonal forces, as Lieven shows in chapters on many different empires, from China to Austria. Emperors ruled heaven as well as Earth: they protected Buddhism in India, chose Christianity for the Roman empire and Shia Islam for Iran.

An explosion of books on monarchs, courts and dynasties has transformed history in the past forty years, and Lieven has read most of them. He believes in a science of empires, which reveals certain “constants about human beings and political power”: the history of empires is a subject as important as economic or gender history. Lieven compares the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb with Stalin, and finds parallels between the Austrian and British empires in their aggressive reactions towards nationalist challenges.

Succession struggles, he also shows, were among the most frequent causes of conflict. The Sunni-Shia split in the Arab caliphate (which had created an empire stretching from the Pyrenees to the Himalayas in less than a century) was not only theological but also “the most important monarchical succession struggle in history,” between the Prophet’s cousins and his descendants. Divisions among the heirs of Charlemagne helped split “Europe’s Carolingian core” into states which eventually became France and Germany.

Love affairs and resentful cadets and cousins could also cause havoc. A strong hereditary line of succession in early Muscovy or the Ottoman empire (despite its remorseless “law of fratricide”) strengthened an empire. Babur and his line gloried in their descent from the great nomad warrior Genghis Khan. Ming emperors built a hall in the imperial palace in Beijing in which they worshipped their ancestors more openly, but perhaps no more fervently, than other dynasties.

The Roman exception of dynasties not lasting more than three generations caused civil wars and coups. Perhaps, however, it strengthened the empire, since it also led to able upstarts such as Septimius Severus and Diocletian gaining power. Usurpation can produce tougher rulers than inbred dynasties. Not until about 1900 did European royal families stop marrying first cousins. In 1888 the Duke of Aosta, brother of the King of Italy, married his niece.

The relationship between structure and agency, between emperors and elites, is another theme. The court was a vital centre of patronage, entertainment and glorification, as well as the ruler’s residence, the seat of government and a marriage and job market. Some emperors, however, felt trapped in a gilded cage. The Chinese Emperor Wanli (r. 1572-1620) went on strike against his ministers, refusing meetings and signatures when they started interfering in the succession. Later the Kangxi Emperor created a “palace memorial system,” permitting a small number of trusted servants to report to him, secretly bypassing the corrupt bureaucracy. Despite having large civil, military and naval cabinets and private offices, however, Kaiser Wilhelm II did not have the focus or industry to control his own government and army — as he learnt in World War One.

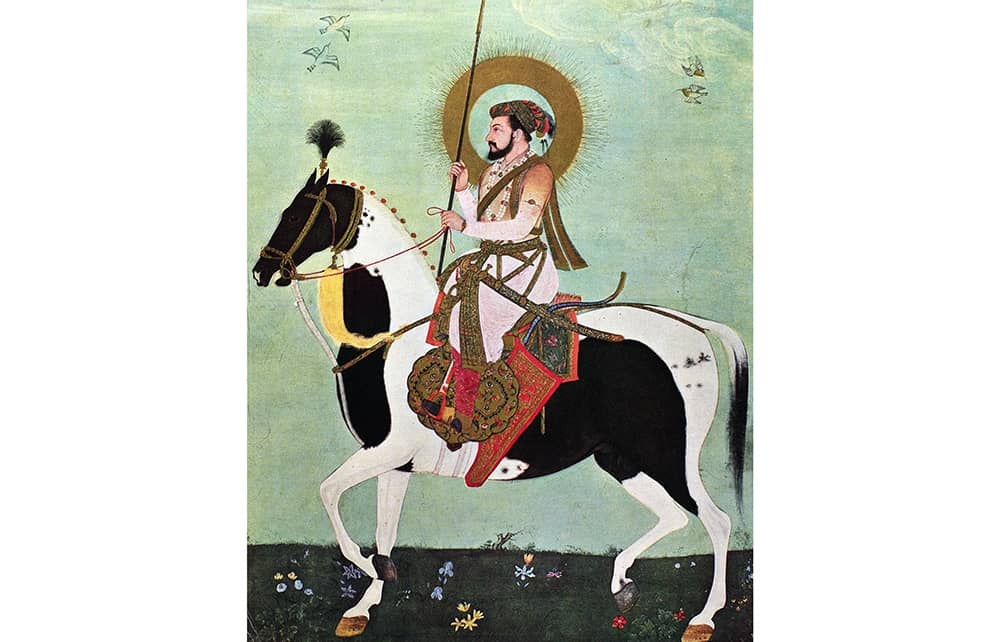

The three principal empires in Lieven’s book are the Chinese, Mughal and Ottoman. Impressive maps help explain the rise and fall of the Tang, Song, Ming and Manchu dynasties. Since empires were usually multinational, racial tensions were endemic. In 1707, the Kangxi Emperor said: “Learned Chinese do not want us Manchus to last a long time; do not let yourselves be deceived by the Chinese.” The Mughals at first despised India as “a place of little charm, no etiquette, nobility or manliness,” as Babur (one of the few emperors to produce an autobiography) wrote. Its only advantage: “It is a large country full of gold and wealth.” His grandson, Akbar, “one of the most impressive emperors in history,” had “the build of a lion” and a “radiant countenance.” Exceptionally tolerant, able to think beyond Islam, he was called “Lord of the Auspicious Conjunction” — the inaugurator of a new millennium. Suleyman the Magnificent also called himself ‘Master of the Celestial Conjunction’, and, in addition, “Shadow of God on Earth” and “Alexandrine World Conqueror.”

Most emperors were conquerors. Charles V, “the first truly global emperor,” who spent one year in Toledo, another in Augsburg and a third in Brussels, was obsessed, as he wrote in 1525, to “cover myself with glory.” Glory was almost always won by the sword.

Emperor Pedro II of Brazil (r.1831-89), also discussed in Helen Watanabe-O’Kelly’s brilliant recent book on new nineteenth-century emperors, Projecting Imperial Power, was an exception. Liberal, intelligent and modest, he had “one of the most successful reigns in the history of empires,” abolishing slavery in 1888, without compensation for anyone. Partly in consequence, he was expelled the following year by army officers with what Lieven calls “narrower and more selfish motives.” This year marks the 200th anniversary of the proclamation of Brazilian independence by his father Pedro I, whose empire appears a far more reliable regime than the current kleptocracy.

There is much else in this exceptionally stimulating book: on empires and nomads; emperors’ exalted sense of their office; their love of jewels, thrones and obelisks; and the ‘extraordinary affection’ for the British monarchy which helped the British government (rather less popular) to rule its empire.

Today Vladimir Putin’s desire to recreate the Russian empire demonstrates again the power of personalities in world history. His invasion of Ukraine (where three empires met — Russian, Austrian and Ottoman) could be as lethal as the German empire’s invasion of Belgium in 1914. Leaders today might remember the terrible consequences of that conflict for the emperors and empires who started it. There are always opportunities to reject war.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.