The striking yet subtle jacket image from Donatello’s ‘Madonna of the Clouds’ announces this book’s quality from the outset. Its focus is drapery, and the way that artists of the Italian Renaissance clothed their subjects, and furnished their narratives, to articulate veils of meaning that were infinitely suggestive. Marshaling a lifetime’s inquiry into the art of that era, Paul Hills — emeritus professor at the Courtauld, and author of the classic Venetian Colour — deploys an X-ray vision to drill beneath the skin, to find the pulse, the heartbeat of a painting or sculptural relief. He offers a key, a new entry point into works we thought we were familiar with; in doing so, he tweaks back a veil between us and them.

The body, naked and clothed, sacred or mythic, remains center stage throughout. From Giotto’s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua to Titian’s late Entombment some 250 years later, Hills explores the potential of fabric in artists’ hands to mediate between the material and the metaphorical, concealing and revealing truths that cluster beneath the surface. The period he writes about was one of growing wealth and luxury founded on the textile trade: silks, satins, velvets and linens flooded the cities of northern Italy, and merchants made a killing. Among these was the father of St Francis of Assisi, and Francis’s first act on realizing his vocation was to fling his costly clothes at the feet of his indignant parent. If power dressing was a marker of worldly success, spirituality lay in nakedness, or the penance of the hair shirt.

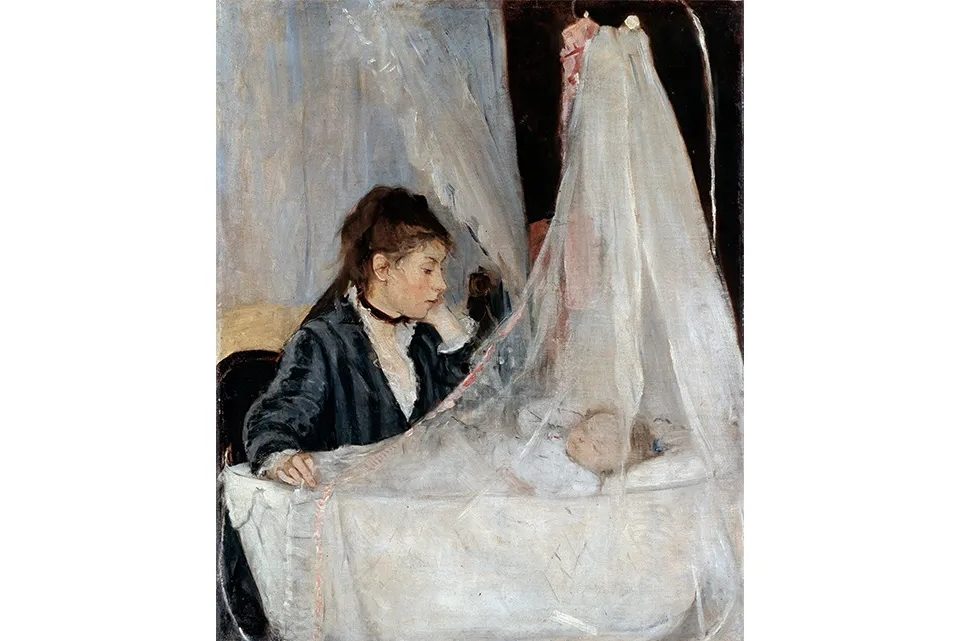

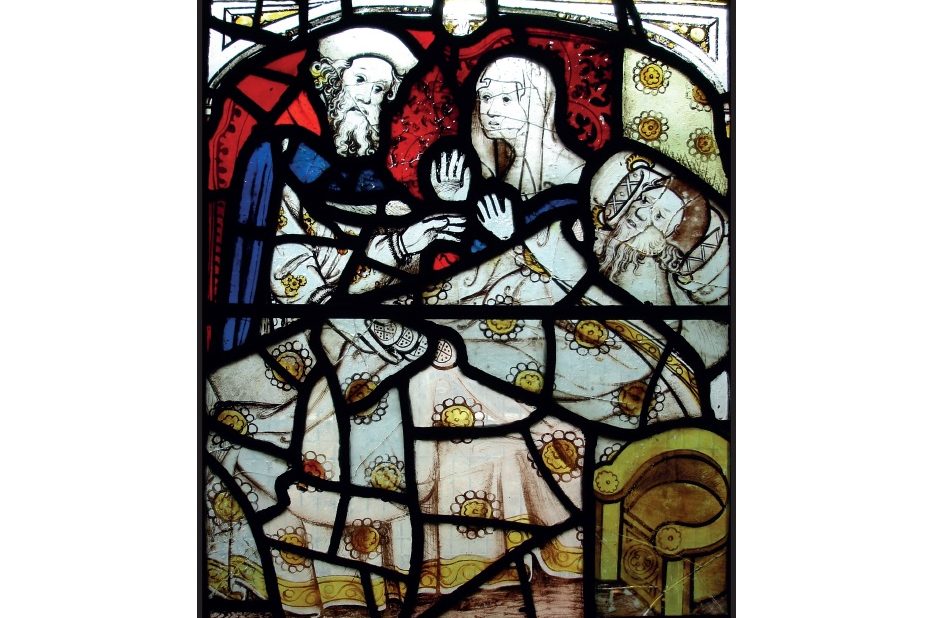

As wealth accrued, citizens decked out their rooms and streets with sumptuous textiles, but as these were too pricey to be widely affordable, householders had to be versatile: they would beg or borrow hangings as occasion demanded — a wedding, the visit of some grandee or a confinement each required a different stage to be set. For artists, a simple domestic interior could now be configured as the setting for an Annunciation or Nativity, hinting at the presence of the Holy Spirit among the hangings and linens of everyday life. Central to Hills’s argument is the way that artists exploited the ambiguity of drapery: the Christ-child’s innocent swaddling bands arranged in such a way that they summoned to mind the shroud in which He would be wrapped after the Crucifixion. And the depiction of the Virgin’s veil, token of her modesty, served alternately to communicate the power and complexity of her maternal love, or to remind us of the grief that she would suffer at the Passion.

It was with Titian, who perfected the technique of layering oil glazes in building his great altarpieces and mythologies, that the veil became not just the subject of painting but the painting itself. Sacred veiling and erotic suggestion chase one another through his narratives, blurring the boundaries between fact and fantasy, animate bodies and inanimate things.

This thought-provoking study, with its ravishing illustrations, made me long to book the earliest flight to Italy, to drown myself anew in the masterpieces of Tuscany and Venice (though, luckily, many of them are to be found in the National Gallery). It is a model of erudition and attentive looking, and of intelligent book design. In his preface Hills writes:

If this book reaches beyond the the walls of the academy to encourage looking again —and looking long — at the sculptures of Donatello and the paintings of Giotto, Bellini and Titian, among others, it will have achieved one of its goals.

For this reviewer, it has enhanced the view beyond measure.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.