On December 13, 1643, a Puritan minister called Richard Culmer borrowed the Canterbury town ladder and carefully leaned it against the Cathedral’s Royal Window. He then ascended the ladder’s sixty-odd rungs, holding a pike; according to his account, modestly written in the third person, “Some people wished he might break his neck.” Culmer had in his sights the “wholly superstitious” depictions of the Holy Trinity, of “popish saints” such as St. George, and in particular of St. Thomas Becket. There Culmer perched, he recalled cheerfully, “rattling down proud Becket’s glassy bones.”

‘Our lives are like broken bits of glass, sadly or brightly colored, jostled about and shaken’

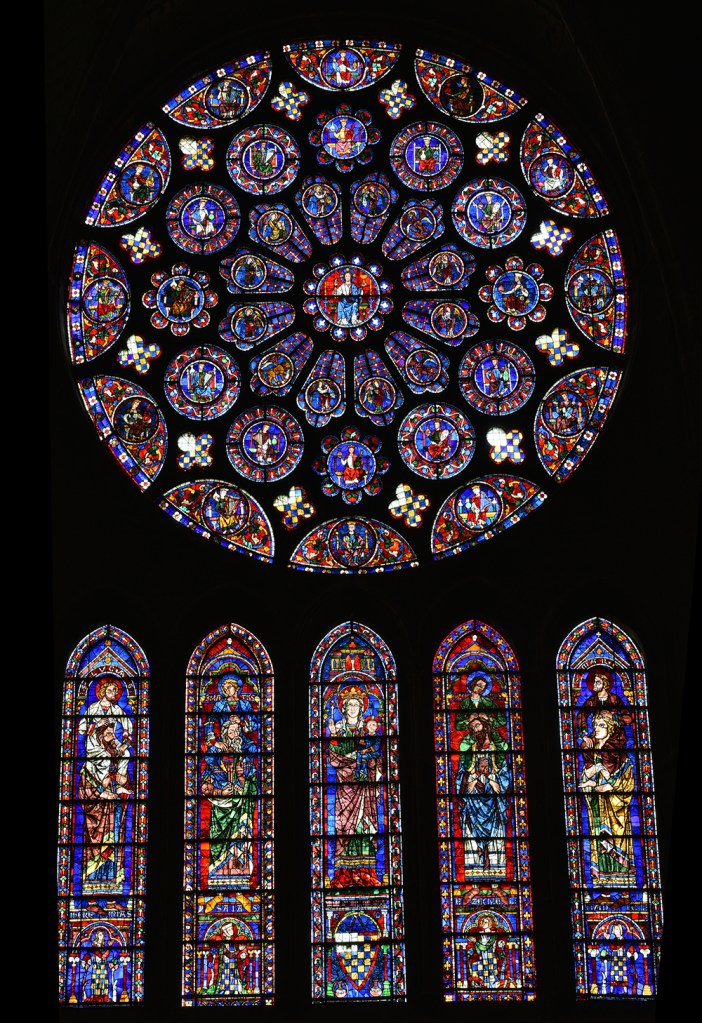

Culmer thus earned a place in the stained-glass hall of shame alongside Henry VIII, who set the precedent by smashing up Becket’s shrine in 1538; Edward VI, who icily decreed in 1549 that allegedly superstitious images should be “defaced and destroyed;” and many of Culmer’s fellow puritans, who wreaked havoc in the 1640s. But it also includes people like the architect James Wyatt who, when restoring Salisbury Cathedral in the 1790s, sold off much of the medieval glass because he didn’t see the point of it. By the nineteenth century, stained glass — especially in Britain — was a kind of lost art needing to be revived. Which, wonderfully enough, it was. Stained glass as a church decoration goes back to at least the seventh century, when — not for the last time — an English churchman hired continental artisans to do a proper job of glazing his windows. The turning-point, though, was the invention of the gothic style. When Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis worked out how to combine the flying buttress and the rib vault, cathedrals no longer needed to be built so solidly. They could stay standing even with huge expanses of window, which could be filled with almost absurdly elaborate creations.

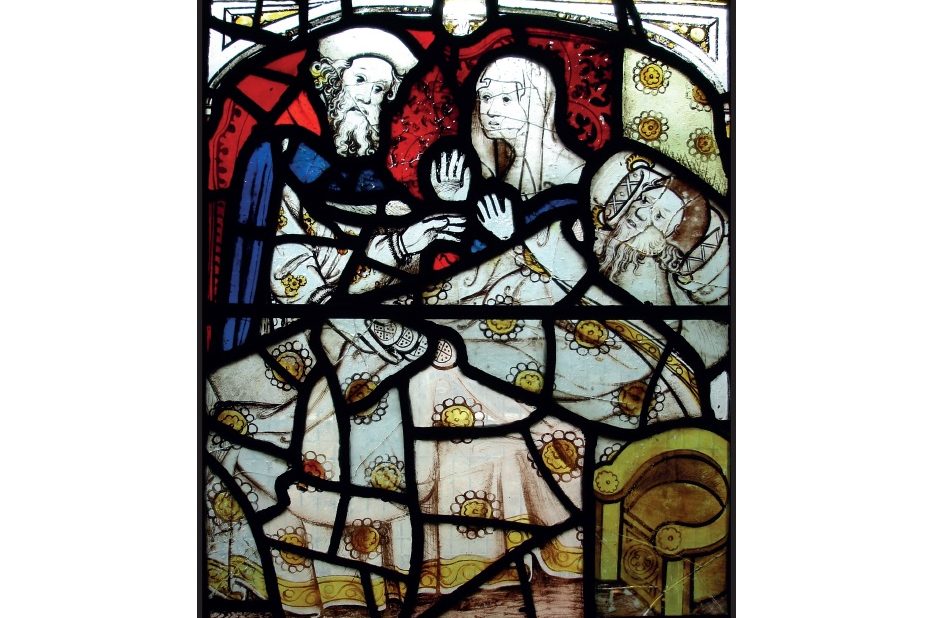

In the first words of the New Testament, St. Matthew opens the Christmas story with a lengthy, albeit selective, genealogy — “Abraham begat Isaac; and Isaac begat Jacob…” — all the way down to St. Joseph, foster-father of Jesus. Most churchgoers find their thoughts wandering when this particular passage is read out. But the glassmakers of Canterbury Cathedral, around the year 1200, combined it with the other genealogy in the Gospel of Luke to construct an eighty-six-window gallery of ancestors.

Stained glass likes an epic theme. At Chartres the north window displays twenty-four Old Testament kings and prophets; the upper chapel of Sainte-Chapelle tells the story of the Bible from the Creation to the life of Christ. The Illuminated Window, a new, exhaustively detailed and comprehensively illustrated book by Virginia Chieffo Raguin, guides the reader through these grand projects. Though of course, with stained-glass windows you don’t need to follow the story. It can be a narrative art, but it also works in the way that a Jackson Pollock does — an explosion of color which, when the eye simply rests on it, evokes an immense peace.

If stained glass is supremely a medieval art, that is perhaps unsurprising, since the Middle Ages loved to speculate on the nature of light. Some believed it was the fundamental element of the universe. It was also a useful way of thinking about how Jesus Christ related to God the Father: “light from light,” as the Apostle’s Creed expressed it. Naturally, then, the modern revival took inspiration from the medieval master-craftsmen.

Typical in this regard was Louis Comfort Tiffany, who in 1865 visited the V&A’s collection and was spellbound by the medieval glass, its deeper colors and varied textures. Back in New York he started his own factory, thus initiating what became American Art Nouveau.

The Illuminated Window follows the American story, through Tiffany and Frank Lloyd Wright, who thought glass was the most effective architectural medium for introducing “the element of pattern.” Raguin only refers in passing to the British revival, which has been compellingly narrated elsewhere by Peter Cormack. Victorian prosperity and religiosity produced a huge demand for windows, many of them beautiful, but some with a rather kitschy feel. It became obvious that you could not recapture the medieval magic through mass-produced nostalgia. You had to channel the spirit of the Middle Ages, and at the same time be true to your own era.

Nobody exemplified this more than the incomparable Christopher Whall. As a young, struggling illustrator in the 1880s, he drew window designs, but was disappointed with what the manufacturers would make of them. So he mastered the technique of stained glass, and wrote an influential manual covering the whole process from beginning to end: how hard to press when you cut glass; what techniques of painting and staining to use on the resultant shapes; what kiln to use when you fire it; and so on.

Whall also gave out some advice on learning the language of color. Leave the city for a few hours, he told his fellow craftsmen, and observe how the “dandelions and daisies against the deep, green grass,” or the pebbles on the beach come together to make an unexpected harmony.

There was a philosophy of life here, too. “Our lives are like the broken bits of glass,” Whall wrote, “sadly or brightly colored, jostled about and shaken hither and thither, in a seeming confusion, which yet we hope is somewhere held up to a light in which each one meets with his own, and holds his place; and, to the Eye that watches, plays his part in a universal harmony by us, as yet, unseen.”

Out of such principles Whall made masterpieces like his windows at Holy Trinity in Sloane Square: intricately symbolic, but also full of a graceful movement that no photograph can capture. Victorian stained-glass saints can look a little anaemic; his have the faces of those who have lived and suffered and come through. The colors are kaleidoscopic and seemingly illogical, until you stand back and let the whole thing overwhelm you. At the very top of the Adoration window he depicts the evening sky in shimmering blue and purple; and at the window’s center the Star of Bethlehem pours down its light on the Virgin and her newborn child.

The Illuminated Window: Stories across Time is published by Reaktion Books. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply