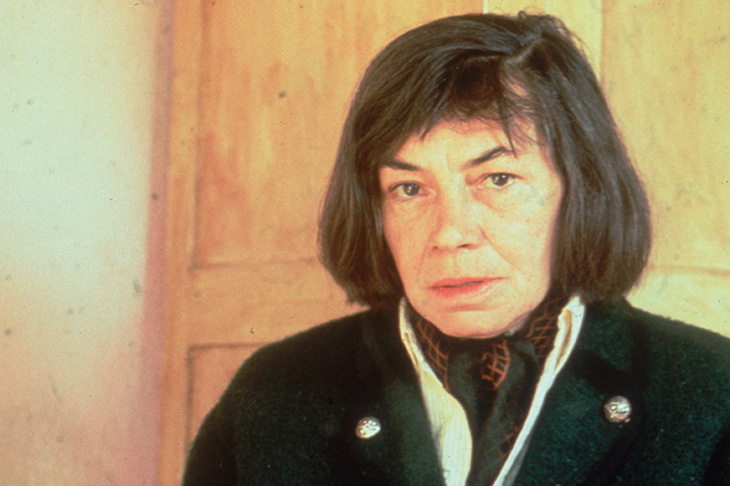

A new play, Switzerland, which opened in London this month, seems to have demonized Patricia Highsmith once again. I cannot quarrel with the overall impression given by the diligently researched biography by Andrew Wilson, but merely say that as one who knew and liked her over many years, the picture seems unfairly partial.

We met for the first time in Florence in October 1952; I was 21, she 31. The Pensione Bartolini stood on the Arno facing the Ponte Santa Trinita. It was on an upper floor, and dominated by a huge dining room redolent of pasta, its windows looking out onto the river. Hardly had Pat Highsmith, lean and auburn-haired, arrived at the pensione than she was commandeered by Bernie, an American painter who had fought in Burma. Bernie plied her with wine and hospitality. ‘Women like that kind of decisiveness,’ she remarked to me.

The studentesco Bartolini was hardly for Pat. ‘Smelly johns,’ she complained and she quit in a few days for a flat across the river. But we began a friendship which would last for many years.

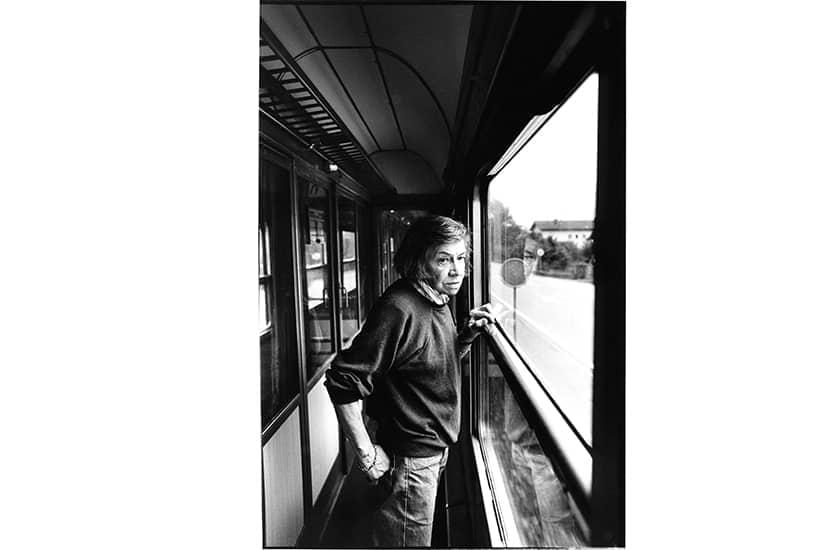

Pat carried with her in her handbag a letter signed by Alfred Hitchcock which declared almost perfunctorily that he would be basing his next film on her novel Strangers on a Train, and offering $50,000 for the rights. It was an ingenious tale of two men who meet in the restaurant car of a train and who agree to swap murders. The book was inventive and original, but Hitchcock all too typically blew it up with a long sequence of pseudo suspense. Unknown to me, Patricia had already published a lesbian novel in the States under a pseudonym.

After she had left the Bartolini, we met regularly, either for meals or for coffee at the riverside hotel the Excelsior. Pat was invariably friendly, modest and humorous. What surprised me, given her substantial success, was her utter lack of any self-confidence. At that time, she was weathering an almost persecutory relationship with one Joan Kahn, her editor at the New York publishers Harper’s, who was demanding rewrites of her last novel.

Meanwhile she was trying to begin another novel, to be called The Blunderer, and showed me its beginning. It didn’t seem to me quite to work, but how could I tell her so? I told her I liked it and in turn gave her my teenaged first novel, The Reluctant Dictator. After reading it she pithily responded: ‘I am sure your taste will improve.’

When it came to my third (and first to be well received) novel, Along the Arno, she was hugely generous and enthusiastic and tried to propagate it in the United States wherever she could.

Much later, when she was living in London, I arranged a small tea party of her English admirers, including the critic and crime writer Julian Symons. Surprisingly, for many years her novels were filmed only in France, sometimes starring Alain Delon, finding favor with Hollywood only posthumously. (Strangers on a Train was the obvious exception.)

She eventually retired to Switzerland. What happened in her declining years seems to have been a sad story, but it was never shown to me.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.