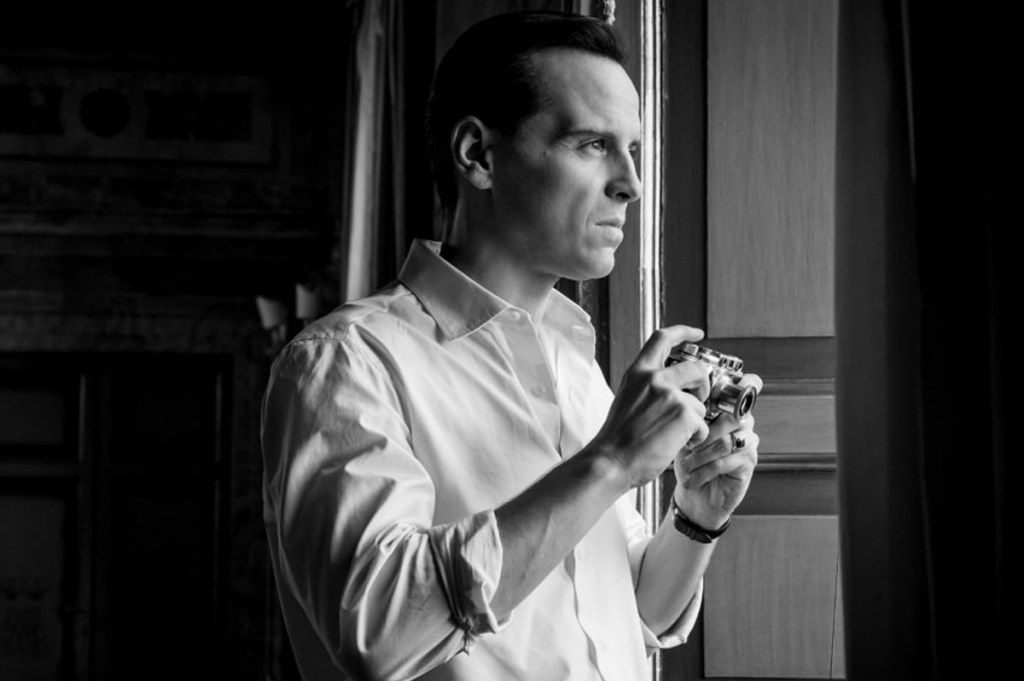

At a time when most streaming shows front-load their first episode with all the drama, intrigue and titillation so that the audience will keep on watching, the opening of Steven Zaillian’s Ripley is almost comically counterintuitive. We see Andrew Scott’s Tom Ripley lugging a corpse down a flight of stairs, without explanation as to who he is or who his victim is, and then we begin the series proper, filmed (by There Will Be Blood cinematographer Robert Elswitt) in crisp black and white. Over the course of eight episodes, Zaillian follows Highsmith’s first Ripley novel, The Talented Mr. Ripley, reasonably closely, albeit with ornamentations and digressions. But if you had any expectation that this would be an edge-of-seat thriller, well, think again.

The original showrunner announced for the adaptation — which was to have aired on Showtime, but has, for undisclosed but probably discernible reasons, been acquired by Netflix instead — was the creator of British thriller Luther, Neil Cross. It is quite easy to imagine what a Cross-scripted Ripley would have been like: fast-paced, viciously violent and portraying its protagonist as a quip-dispensing anti-hero who moves through Italy, murdering as he goes. The Zaillian version is quite different, being instead a deliberately paced character study that focuses on its murderous lead with almost glacial stillness.

Anyone who has seen Anthony Minghella’s magnificent 1999 adaptation of the book will know the contours of the plot, and indeed this is (deliberately) wildly and wholly different. Minghella’s film was sorrowful and compassionate, suggesting that Ripley’s actions stemmed less from a desire to hurt than from a frustration at not being able to love and be loved; its most devastating moments take place when Ripley does, indeed, kill the things he loves, whether out of frustration or, finally, because it is the only way that he can escape detection and justice.

Zaillian’s series, meanwhile, plays with its audience rather like Andrew Scott’s amused, unreadable Ripley deals with the various dupes, accomplices and victims that he faces. If you don’t care for him, that’s because he doesn’t want you to. There is an extended scene in the third episode in which Ripley, having committed a murder at sea, is faced with the unpredictable consequences of his actions, and it’s both Hitchcockian in its emphasis on tiny details and curiously removed from any attempt at making the audience feel anything other than a slight sense of horror and trepidation. This is, of course, the point.

Zaillian has never been any slouch at tantalizing and thrilling his audiences, whether as a writer-director — he was responsible for the excellent The Night Of — or as a screenwriter who wrote everything from Mission: Impossible to Hannibal. Yet he may still be best remembered for his screenplay for Schindler’s List, which took a similarly, and intentionally, detached approach to acts of enormous cruelty. It would, of course, be irresponsible to compare Spielberg’s depiction of the Holocaust with Zaillian’s account of the murderous intrigues of a conman, but there is a similar formalism in the filmmaking, helped by the black and white cinematography, that disturbs even as it fascinates.

The series would founder if it weren’t for its lead, and Scott’s magnificent performance at the center surpasses even his noted work in the recent All Of Us Strangers. He’s an older Ripley than the book’s twenty-five-year-old protagonist, but this works beautifully. The sense is given that he has been bumming around New York for years, ducking and diving in his small and unambitious cons (we see the amounts he is trying to scam through mail fraud — forty or fifty dollars) until, finally, he is given his big break when he is asked to head to Italy to retrieve Dickie Greenleaf (Johnny Flynn), the wealthy but indolent playboy son of the magnate Herbert. Marge Sherwood (Dakota Fanning) mistrusts Ripley on sight, later remarking, “Everything about Tom is perfectly vague — intentionally so,” but Dickie is half-seduced and half-convinced by him, until he isn’t. Yet as portrayed by Scott, there’s nothing really to Ripley under the smile, making him a body snatcher of sorts who can hope from identities and personae with ease and a practiced charm.

It remains to be seen how Ripley is received by audiences and critics alike. If it’s successful, then hopefully Zaillian and Scott will be allowed to film the other four novels that make up the so-called “Ripliad.” And if it isn’t, well, at least we’ll have this stylish and profoundly intriguing exercise in garnering sympathy for this particular devil.

Leave a Reply