On Sunday, November 10, 1991, the band Tin Machine played a gig at Brixton Academy in south London. Brixton then was far from the gentrified area it has become; it remained a hotbed of simmering social and racial unrest. The notorious riots of a decade before were still a recent memory, and those who ventured to the Academy did so in the knowledge that fights and aggravation were highly likely, especially after alcohol had been consumed. But if on-street scuffles were a price that gig-goers had to pay to see their musical idols, the world of Tin Machine was a much less happy one.

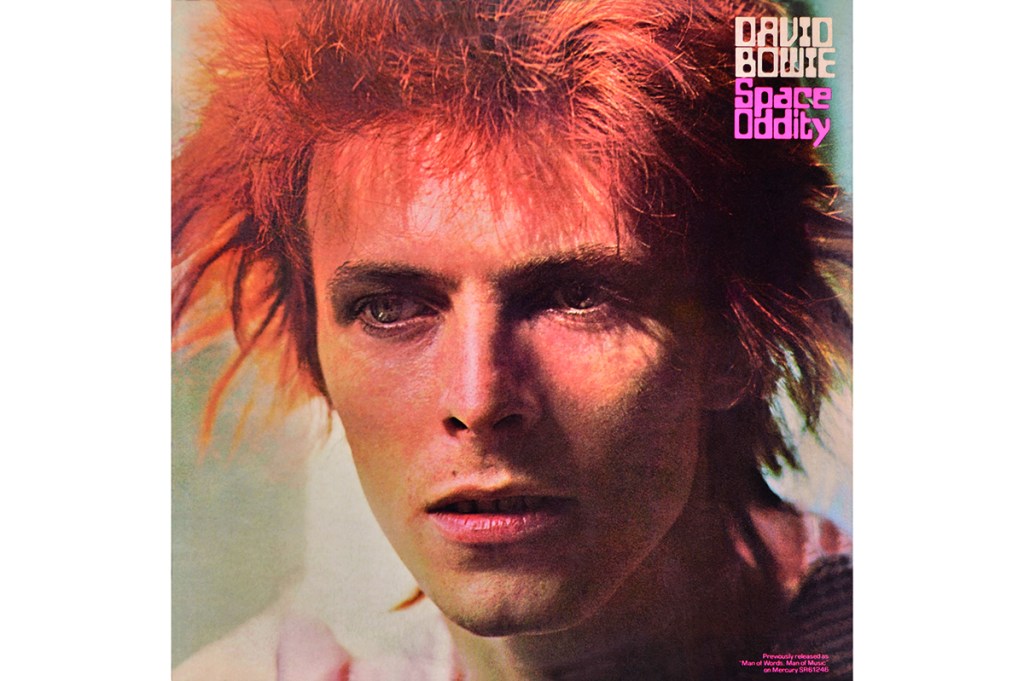

At the beginning of the Nineties, David Bowie had to consider, for the first time since the success of the single “Space Oddity” in 1969, that he might be a spent force. After his colossal commercial and artistic achievements of the Seventies — interspersed with a chaotic and eventful private life, as was obligatory for any self-respecting musician of the time — he had a vast commercial success in 1983 with the Let’s Dance album and single. This established him, against the odds, as a pop sensation to rank among his far younger peers. But his subsequent Eighties albums were met with disdain (and 1987’s Never Let Me Down, his artistic nadir, was subsequently all but disowned by Bowie). So, in near-desperation, Bowie hit upon a new idea: he would form a hard-rock band, treat it as a democracy (even if he wrote or co-wrote all the original songs) and try and reinvent himself once again.

For the first time in his life, this reinvention failed. The first, eponymous Tin Machine album was released in 1989 to poor reviews and weak sales, and its 1991 sequel was ridiculed for allowing the band’s drummer Hunt Sales to sing on two of its tracks. By the time the tour reached Brixton, there was a genuine sense that Bowie had reached a creative low point, as well as a personal one. It was therefore with a sense of homecoming that, as Tin Machine’s tour bus neared the Brixton Academy, Bowie asked that they divert to 40 Stansfield Road, where he was born January 8, 1947, and lived until he was six. As they reached his old house, Bowie asked the driver to stop, and looked at it with veneration. One of his bandmates saw him weeping, as he quietly said, “It’s a miracle. I probably should have been an accountant instead.”

Tin Machine disbanded shortly afterwards, and Bowie’s subsequent career resumed its successful trajectory, albeit interrupted by a near decade-long absence from the industry due to a heart attack in 2004. While it was a running joke in the music press that every one of his albums was hailed as “his best since (1980’s) Scary Monsters and Super Creeps,” there are remarkably few weak albums in a run that began with 1993’s Black Tie, White Noise and ended with 2016’s extraordinary Blackstar, the swan song released a few days before his death from liver cancer, at the age of sixty-nine. That album was initially received warmly but with faint confusion by critics, who called the lyrics opaque to a point of obscurity. Once it became clear that Bowie intended Blackstar to be a final will and testament of sorts — although expecting clarity from so mercurial an artist is a fool’s game — it became all too clear that lyrics like “Look up here, I’m in heaven / I’ve got scars that can’t be seen” had the most poignant of double meanings.

The reaction to the announcement of Bowie’s death on January 11, 2016 was an extraordinary outpouring of grief on both sides of the Atlantic, and beyond. Fans headed to Brixton and sang his songs in the streets; in New York, meanwhile, his admirers placed bouquets outside his SoHo apartment, with one simply saying “Starman Forever.” It was clear that this was no ordinary reaction to the death of a rock star, but a global sorrow at the passing — at least a decade before his time — of the man who had reinvented not just himself but conventional expectations of popular music throughout the latter third of the twentieth century. A plethora of books, some very good and some very bad, were rush-released to capitalize on the mourning, and countless compilations and hitherto unreleased songs have subsequently been made available. This included Bowie’s famous “lost” album Toy, a collection of rerecorded cover versions of his old songs that was due to have been released in March 2001, but never appeared: a victim of record-label scheduling conflicts and the faint sense that Bowie was no longer the commercial titan he had been two decades before.

Of the various documentaries about Bowie, by far the most comprehensive and impressive is Brett Morgen’s 2022 Moonage Daydream. It is a jaw-dropping visual and aural feast that eschews the usual conventions of the genre — a celebrity narrator, talking-head interviews — in favor of an impressionistic collage of live performance, rare backstage and candid footage, and a kaleidoscopic marriage of (appropriately enough) sound and vision. The only narration here is a compilation of Bowie interviews; over its two-and-a-quarter hours, it does the closest thing to bringing the man back to audiences that any film can, thanks to Morgen being given unprecedented access to the zealously guarded Bowie archives. It was received rapturously at its premiere at Cannes and has been a significant success on IMAX screens in the United States: proof, if it were needed, that Bowie continues to be big business years after his death.

Yet there remains a tension between the longed-for purity of Bowie’s legacy and the increasingly ravenous actions of those adjacent to his estate. Since his back catalog was sold, in a rumored $250 million deal, to Warner Chappell at the beginning of 2022, there is a tangible sense that the reins have been loosened, and that Bowie’s music has been featured and used far more readily than it ever was in his lifetime. It is not uncommon now to see his songs appear in commercials, and after the exercise company Peloton licensed his entire catalog, a variety of remixes have been commissioned, much to the horror and disappointment of his most diehard — some would say conservative — fans. And although the 2020 Johnny Flynn biopic Stardust, which was denied the rights to use his music, was met with critical derision and box-office failure, it is rumored that a biopic, tentatively entitled Starman, has quietly been in development for years, and that as soon as permission is obtained from the Bowie estate, it will move into production.

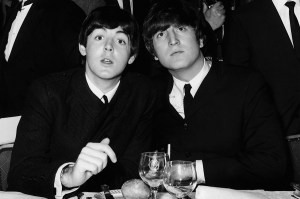

Films about musicians tend to have mixed success. For every Oscar-winning megahit like Bohemian Rhapsody, there is a more modest example (see Rocketman), and any feature about Bowie might struggle to capture his extraordinary life in two hours. The alternative might be a more expansive Netflix series, but as the failure of Danny Boyle’s Sex Pistols show Pistol demonstrates, length and a higher budget do not mean that an artist’s life and career are captured any better given more time. There has never been a definitive fictional representation of Bowie’s sometime friend and collaborator John Lennon; perhaps there never will be. But Lennon was such an articulate — if often disingenuous — promoter of his own legacy that it seems barely necessary.

If Moonage Daydream reminded audiences of anything, it should be that Bowie, like Bob Dylan, contained multitudes. In addition to his extraordinary musical talent, he remained a likable and accessible figure, self-aware enough to see the ridiculousness of the industry that he played such a major role in helping to sustain, and possessed of an enormous charisma that raised everybody around him. In 2006, I saw his final performance in the United Kingdom, when he guested at a David Gilmour concert at the Royal Albert Hall. He came on in the encore to sing the Pink Floyd songs “Arnold Layne” and “Comfortably Numb” to a rapturous reception; it was widely believed that he had retired from live performance (as, to all purposes, he had) and so this last cameo appea ance was a final hurrah, although nobody in the audience knew it. As Bowie looked out over the thousands of delighted faces and heard the ecstatic applause, he grinned and said “My, my, my, I hope I warrant that.”

It was this ability to warrant respect, admiration — even love — throughout his career that has meant that Bowie’s true legacy remains undiminished. He might have wept in a tour bus in South London one Sunday in November, but over three decades later, David Bowie’s heroic stature as rock music’s greatest iconoclast shows no serious signs of being threatened. Sorry, Harry Styles, but the original Starman will outshine you from the grave, and beyond.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2022 World edition.