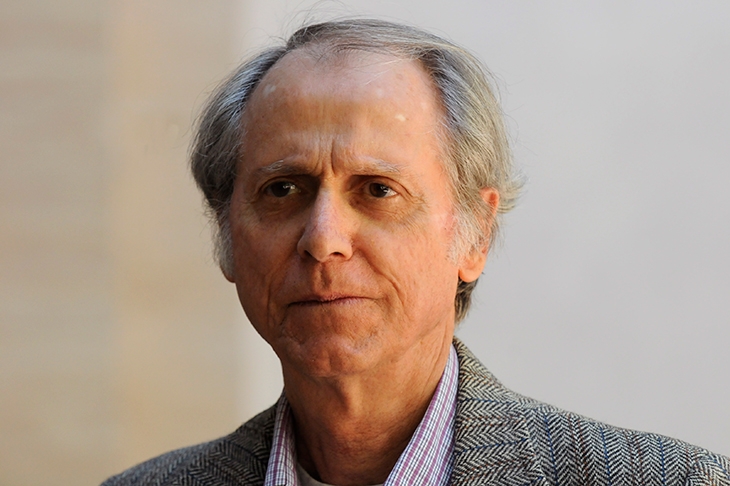

Elaborated over a writing career that spans half a century — a career crowned with every honor save the Nobel Prize — Don DeLillo’s great project has been to explore a world where paranoia is not only warranted but healthy, a sane response to imminent threat, man-made or otherwise. He didn’t win the Nobel again this year, and may never, but his literary stature remains colossal. He’s revered as a writer and also as a prophet, a bard who sings our future into being.

His very short, bracingly bleak new novel The Silence is DeLillo distilled. Anyone who doesn’t like the taste will find it unendurable; for fans it’s a straight shot of the good stuff.

The first scene is wholly static: a couple buckled up in their seats on a plane bringing them home from Paris to New York. Bored, exhausted, unable to sleep, the man, Jim, begins to recite the information on the screen:

‘“Okay. Altitude thirty-three thousand and two feet. Nice and precise,” he said. “Température extérieure minus fifty-eight C… Arrival time sixteen thirty-two. Speed four seventy-one mph. Time to destination three thirty-four.”’

Jim’s wife, Tessa, a poet, is hunched over a small blue notebook, writing. ‘Filling time. Being boring. Living life.’ The stasis, the boredom — it’s all a lie, a comforting delusion. As Jim’s recitation ought to remind us, they’re hurtling through the sky, defying gravity, risking death. They’re heading in fact for a crash landing.

Jim and Tessa are expected later that afternoon in the Manhattan apartment of Diane and Max. It’s Super Bowl Sunday, 2022, and the two couples and another man, Martin, were supposed to watch the game together, a banal American ritual. But something inexplicable happens: just before kick-off, the television goes blank, the phones go blank. It’s a blackout and a cyber apocalypse, a catastrophic failure of the systems we depend on, another crash landing, this one exposing the fragility of our digitized world. Is it a cyber attack or merely a massive technical fault? No way to know, though Einstein’s famous prophecy haunts the book: ‘I do not know with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.’ DeLillo uses the remark as an epigraph, and Martin, a physicist obsessed with Einstein’s 1912 Manuscript on the Special Theory of Relativity, quotes it.

Having survived the plane crash (‘We have to remember to keep telling ourselves that we’re still alive’), Jim and Tessa join their friends as planned. The party carries on, a candlelit wake in front of the blank television screen, a postmortem spasm:

‘All five individuals sat and ate.’ The second half of the novel is punctuated by monologues, each character in turn giving voice to a troubled recognition of the new reality.

[special_offer]

Here is part of the poet’s aria:

‘“What comes next?” Tessa says. “It was always at the edges of our perception. Power out, technology slipping away, one aspect, then another. We’ve seen it happening repeatedly, this country and elsewhere, storms and wildfires and evacuations, typhoons, tornadoes, drought, dense fog… skies blotted out by pollution. I’m sorry and I’ll try to shut up. But remaining fresh in every memory, virus, plague, the march through airport terminals, the face masks, the city streets emptied out.”’

After the virus, what comes next? A blank screen that gives no answer. Or is the answer. And the voices of these five people, and DeLillo’s familiar, distinctive voice? There to remind us that we will always try to make ourselves heard, to make a mark, even as end times approach. Meanwhile, Tessa’s advice is as good as any: ‘Tend to the simplest physical things. Touch, feel, bite, chew. The body has a mind of its own.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.