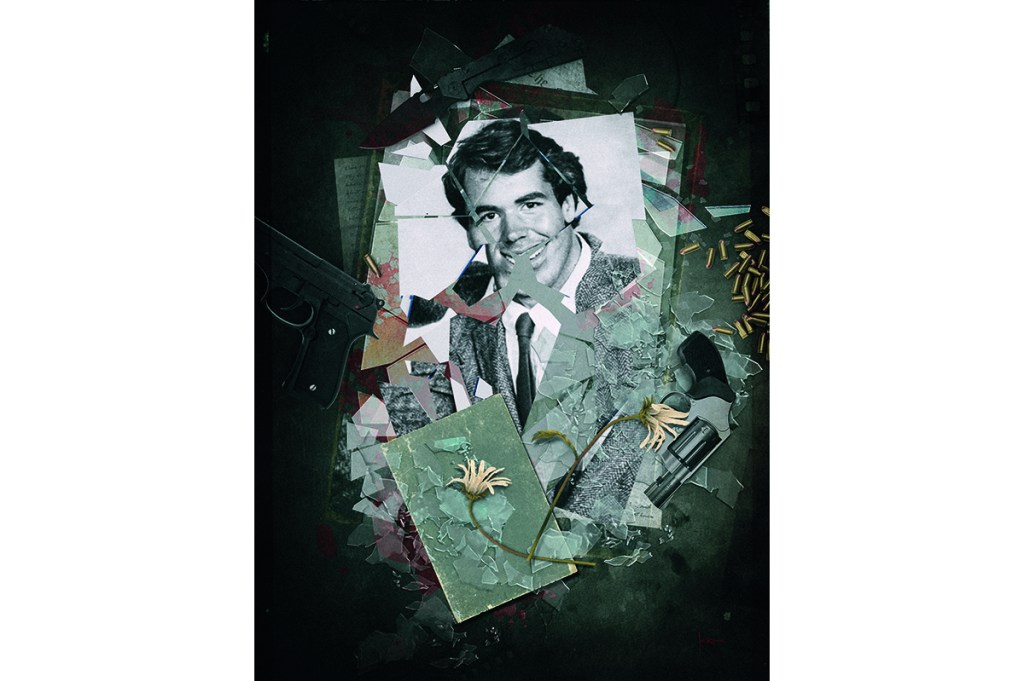

The Shards is about 600 pages long. “Should anyone even publish a 600-page novel?” asks its author Bret Easton Ellis. “I happen to believe, yes, if it’s justified.” Such books are rarely justifiable, and often, novelists become buzzed-about simply for executing them, but not many can boast that every word, scene and sentence is necessary. This is how it feels to read The Shards: not a detail is to be missed. It contains the thematic elements that run through Ellis’ oeuvre: the social lives of the wealthy, or nearly wealthy, drugs, sexuality and desperation painted over with bursts of violence.

The through line that connects his work isn’t that sex and violence are taboo. What becomes crystal clear is that society at large is uninterested in the depth of human suffering that occurs around them. The suffering is a footnote. Everyone wants to get on with their lives; they don’t want to think about it or necessarily feel it.

Bret Ellis, the seventeen-year-old narrator of The Shards, finds himself in the most ecstatic moments with Matt Kellner, a boy he is secretly sleeping with behind his girlfriend’s back. Bret has feelings, deep feelings, something that lives above sex. But of course, Matt doesn’t feel this way, and this strikes a theme that Bret, the narrator, knows will become resonant in his life. There’s a scene at the end of their first tryst when Matt Kellner tells Bret, “You think we’re gonna be boyfriends? Are you fucking crazy? Get away from me.” Bret returns to his car, alive, after seeing any emotion pour from Matt for the first time and breaks down into tears. This theme of rejection, of otherness, becomes unrelenting as the work builds up. By the time I hit page 593, I was in tears. I closed the book, my face wet, basking in its totality.

As a writer, his eye is maniacal and unsettling. There’s not an ounce of reluctance in it. It is focused and sharp throughout. He is not chronically online or driven by the zeitgeist; he doesn’t tweet anymore, and his Instagram is sparse and promotes only his podcast, though it’s occasionally dotted with photos of celebrities at dinner. In some ways, this distance makes Bret Easton Ellis the last of his kind — an outsider who is both glamorous and gritty; a writer who is both worshiped, like a movie star, and pushed to the fringes by critics who’ve turned him into “the worst-reviewed writer of my generation.”

Elle Nash: There were some moments throughout The Shards that dealt with rejection where I would tear up a little. And I was like, “Oh God, it’s going to happen. I’m going to cry…”

Bret Easton Ellis: Well, you can imagine how I felt writing this book…

EN: The narrator says he began writing the book last year, which, at this point, would be 2020. Is that really how long the book took to complete?

BEE: Well, I did, but I had been carrying the idea of this novel around since 1982. I was going to put aside what I called the Less Than Zero project, which I’d been working on earnestly since tenth grade. Sometime in my senior year, this book appeared. I think one of the reasons why it came together in April 2020 was that it was simply time. I was so much older. When I attempted it in 1982, it was narrated by an eighteen-year-old; there was no backstory. It was just the characters and the events, all done in minimal present tense. Writing it at fifty-seven, I realized this was a novel narrated by a much older man looking back on that year, able to flush it out and see it in a way he could never have possibly seen at eighteen or twenty-eight. It came really easily.

I remember the night I began it; the pandemic had started. We were all in lockdown, there was nothing to do, and I was starting to open a bottle of wine earlier than usual. I found myself doing something I really don’t do that often; I went to YouTube. My boyfriend was playing video games, and I would come in and have a drink and then go on YouTube and just look around. I’m never on Facebook ever or Instagram. I mean, I have accounts, but they’re all handled by Knopf and publishing people, by podcast people. I started to listen to music from that time (1981-82). Then I started to look for some of my classmates that I hadn’t seen in forty years. I couldn’t find some of them. Some of them simply had no Facebook account, no social media, which didn’t really surprise me. I was haunted by the fact that they were gone.

Then I began to look around for the places we hung out back in high school; they were all gone. Most of them are razed: the clubs, the theaters, the Galleria, and I just had this huge pain of nostalgia and nothing else to distract me. Nothing else was going on, so I automatically started writing this first chapter. Because of the time we were in, and nothing was going on, I wrote it in about sixteen months. Everything had stopped. I started in April 2020, I finished it in September 2021, and it was just a very intense, focused thing that gripped me.

EN: It’s interesting to me that you went twelve years without writing. How did that feel?

BEE: I really thought Lunar Park was my last novel, and then somehow Imperial Bedrooms came about in a very weird, tortured way. Then I thought, I’m done. I want to make movies. I want to direct a film. I want to create a TV series. I’m very committed to this. I really want to do this… but nothing gets made. Very little gets made. In 2020 I was really thinking, where is the novel? I want to write prose, and one of the things that was very pleasurable about putting White together, even though it was nonfiction, was the prose writing. I was going back to prose writing. I find it interesting that at fifty-seven, I was able to write my longest novel in a condensed period. It took me about eight years to write Glamorama and I was so infatuated and so horny for that book. I was so obsessed and just kept wanting to have an affair with it.

EN: I was delighted to hear your talk with A.M. Homes. She hadn’t published a book in a very long time, either. When I read The End of Alice I think what affected me most was I thought, “This book is so good, but it could not be published today.” There’s a grandfathering in of risky material like hers.

BEE: Not by a mainstream publisher, but I think there’s a lot of stuff out there being published that’s kind of like, wow, but it’s just not by Random House or the big three.

EN: If what’s being published by mainstream publishers isn’t very risky, what do you think is the future for the landscape of American literature?

BEE: The future of the novel — I have to say, it’s so funny. I don’t care. I don’t care about the future of the novel. I used to care, but I’m just content to live in my little world. I read a lot of novels. Though, not as many as I used to. I have so many other things to worry about, or that concern me than something that big and that vast. I think what you’re really asking is, what kind of fiction is going to ultimately be published, if it is a risk-averse business in terms of material and content… I read about books, and I pick up books because I read reviews and I do see things on social media and think, “Oh, that sounds interesting.” I am interested in books, and I’m interested in good novels but I’m not so concerned about the future of the corporate entity that controls the way fiction gets out there and is delivered to massive audiences. That’s much harder for an independent publisher or a small publisher to do.

I’m glad I came of age when I did and when there weren’t all these ideological concerns about content. Maybe that’s why I feel so sort of blasé about it. You hear whisperings about The Shards as a negative portrayal of homosexuality. I heard there were weird concerns about not having it portrayed in a more positive, upbeat light. But Dahmer is the most popular show Netflix has ever put on, so I think maybe we’re moving out of that. I was very disturbed by Dahmer. We watched it the first couple of days it and I turned to Todd and said, “I kind of like this, but who in the hell is going to watch this?” And it turned out, everybody — everybody was interested to see it.

EN: The independent literature world is very vibrant and promising right now. They just don’t have the million-dollar marketing penetration.

BEE: Right, and an author needs that, and a book needs that to at least make a dent. But go to Goodreads. There are thousands, hundreds of thousands of people out there reading books and trading reviews and putting stars up and there’s access to groups of readers in ways that are unimaginable to me through the internet. So, you can complain about that, but obviously, there are readers out there. I mean, who’s the big writer? Colleen Hoover is the big writer right now and has like ten bestsellers all over the place. TikTok has been helping sell books in ways that are unheard of.

EN: I just try to read.

BEE: The only thing a writer needs to do is read. That’s it. That is the only advice I ever give a writer — to read all the books you can. One thing that a writer does need is style. Style is the hallmark of a real writer. I think without style, it’s just a bunch of empty gestures. Style is the cohesive thing that brings everything together that lets you into the consciousness of the book. If you got that, you’re pretty much going to be OK.

EN: How would you define that?

BEE: It asserts itself in a way. You think, “this person can write and it’s going to take me through the story.” Or when they don’t, you can be fifteen pages in and go, “OK, I get it. They only want to tell the story.” They’re just telling you exactly what happened and that’s a little less interesting to me.

EN: I find there will be movies where that’s all it is — they spell it out for you. Then you run into a movie that has amazing dialogue and you’re like, this person is giving me something real, rather than just giving me a plot point to move something along.

BEE: I think a close-up of someone changing their mind about something is the greatest special effect. I don’t think movies depend on dialogue as much as they should depend on atmosphere and mood and visuals. Talky movies can be slightly alienating without the visuals to go with them. So, I don’t know about that, but yes, I know what you’re saying. It’s about talent.

EN: It’s also the collaboration between a good actor and director — how those things come together.

BEE: You don’t even have to be a really good actor. You can be a movie star. A movie star is what we want to watch. There’s this fantastic documentary about Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward on HBO. Paul Newman said, “I was not a good actor, I really wasn’t. I looked good on screen, people would throng to me like hell because I was so good-looking. And I did my thing, but I was not really a classically trained actor and I only really play certain kind of men if you look over my career.” I think that’s probably true for someone like Robert Redford or John Wayne, too. In the history of movies, movie stars are what we want to see; we want to fantasize about them. I think we’re all bisexual when we go to the movies.

EN: When I was listening to your talk with A.M. Holmes, you discussed books that predict something; her book ended with the school shooting — released on the day that Columbine happened. Do you have any superstitions around your writing?

BEE: The only thing I often was superstitious about, and maybe why I kept writing for so long and working on a particular book, was that something terrible was going to happen to me if I finished the book. I would either get a terrible disease, I would be in a horrible accident, or someone would get me and that was just part of the drama I think a novelist encourages about himself because it is true. It is not method acting — writing a novel is not method acting — but it’s larger than that. It’s your persona. It’s what The Shards is about and why I wanted to address that, as young as I was. I think the writer I was in high school was kind of a drama queen, and I was creating drama. I was a bit of a liar. I did have a girlfriend and I was gay. I did have a secret boyfriend because he was “in the closet.” And I believed he was completely in love with me, and then I believed my parents’ friends were this-and-that, so I had this entire out-of-control writer’s mentality. And it all came crashing down. That’s when I wanted to write The Shards.

EN: You once described feeling liberated from some of the issues with your father after you finished Lunar Park. What has The Shards liberated you from?

BEE: That’s a very good question. I felt I had honestly relayed my feelings, and to a degree, my apologies to those that I may have hurt when going back to that period [in The Shards], explaining who I was in a way that I couldn’t articulate at eighteen. If there are people who will even read this book from back then, I would hope that would be their takeaway. That I really loved you all. I really did. I was young and foolish and I got so many things wrong and I hurt people and it was a massive learning lesson…I think I was forgiving myself, as well, for whatever I did, whatever my transgressions were. Certainly, to the girlfriends, certainly to the boys I’d been with, certainly to whatever friends I might have hurt from my crazy imagination… I was also going through a lot of bad stuff while I was finishing up The Shards. My boyfriend had gotten addicted to drugs, and he was arrested, and he was in jail then he was homeless. All of this stuff was going on as I was finishing the book, and yet the book was the solace. The book was my answer. There was nothing I could do about that, that had to play itself out. The novel was that beautiful thing to go to where I could disappear into it for hours and hours and hours. That’s where I go. That’s the escape.

EN: You know how musicians have that one hit song they hate? Do you have books you feel forced to confront all the time, and you’re like, “I don’t want to think about this book anymore…”

BEE: My feelings about all the books have changed over the years. I have a different relationship with them at certain ages than I did when writing them. It’s interesting to be confronted with that and to realize, well, what is my relationship to Imperial Bedrooms, a book I barely made it through? It killed me to write that book, and I didn’t quite like it. Everyone wanted me to publish it because it was the sequel to Less Than Zero, but now it’s my favorite book. I picked it up and looked through it three years ago and was amazed at the pain radiating off the page.

EN: Do you still feel good about The Canyons, your movie with Paul Schrader?

BEE: Yeah, better than ever. I always liked The Canyons. That movie was so controversial, there was so much written about it, and so many people hated it upon release. Schrader was confused. We had about $250,000 to make that movie. I thought Schrader, how he did it, he made it look as good as it did, it was remarkable. I don’t think I could have done it. I watched it recently, and I thought, God, we had zero money, and I banged out that script in three or four weeks and we just made that movie to see if we could make it. Schrader didn’t change a word. He shot the script, my script. I thought there were some weird tonal things we didn’t have enough time to reshoot. But I like that movie a lot. We sold it to IFC for over a million dollars, so everyone got repaid, and Lindsay got her money. Everyone likes the story that the movie didn’t make any money and that it’s terrible. There’s still jokes made about it, but I completely stand by it.

EN: Do you identify with the label “transgressive fiction”?

BEE: I first heard it with Dennis Cooper’s work. Closer was being published, and I hadn’t read Dennis before Closer. I read it, and I was really impressed. I got to know Dennis later on. I did think, if this fiction is anything, it is completely transgressive against the mainstream and what our norms and proprieties are, and I really admired it because of that. I think Chuck Palahniuk took it in a far more mainstream direction. I didn’t read Dennis Cooper until two or three years after American Psycho was published. I mean, if people want to label me something, they can label me whatever, but I really don’t care… If I’m transgressive, I’m transgressive. I have always felt I’m a bit of an outsider in terms of the mainstream, and I don’t care. Transgressive, sure, I’m happy to take that.

EN: Do you feel like scenes necessitate good art? In the sense that there’s a writer scene in New York City or LA.

BEE: No, absolutely not. I’ve been in a couple of really big scenes. I was in the late Eighties Brat Pack scene. And past that, the young novelists in New York, the Nineties thing. I went through the Bennington Writer’s Workshop, which is now a thing. There are podcasts made about it and articles, and there’s a movie coming out. I just found myself in them. I don’t think it did anything in terms of affecting my fiction or making me happier or making me sadder. It was just a group of people. I have not been in a writer’s scene in about twenty-two years. I’d have to go back to Manhattan at the end of the Nineties where, yes, you were a writer, you knew all the other writers, you knew the publishers. You’d go to writing parties, there were book parties. I mean, it was very different. There was so much more money, it was so much more glamorous. I remember Jay McInerney and various writers doing photo shoots in Calvin Klein for GQ or Rolling Stone and being on red carpets for movie premieres. It was a very different time in terms of being a writer and a writer having that built-in glamour associated with them. But I also know it was incredibly bitchy and competitive. Very dramatic. It was a time when you would go to a book party in Manhattan, and you’d see Joan Didion and Norman Mailer, and over there would be Susan Sontag. I think that moment is gone. I felt that when Philip Roth died, Joan Didion, that was it. OK, that’s the end of an era. But I am older. If I were younger right now, thirty-two or thirty-three, maybe I would be pointing to writers and going, oh, it’s… but I don’t see this anywhere. Everything’s so fractured now.

EN: Did you ever think that you would end up the type of writer who’s had the effect you’ve had on American culture or American fiction? Did that ever drive you?

BEE: Well, where I am, darling, I look at myself as a failed screenwriter living with a guy twenty-three years younger than me in a high-rise condo in West Hollywood, and how am I going to pay for the piping that needs to be redone in all my bathrooms? That was the concern today. Very unglamorous, by the way. Phone call to the plumbers, then the building manager came up. And I have to go to the market to get some food. I mean, it’s not as if I wake up in my mink bed and I look over all the accolades and my Pulitzer and my National Book Award to go, “yes, I am the king of the writers.” I look at my life very practically, and I don’t connect. Whatever my influence was, was purely something that happened and that you can’t decide. I mean, I’m sure every writer says, “I want to be the most influential, and I want to inspire people or be this person.” And you can’t help it. There is a part of every writer who dreams about this. I think it’s just innate, and I think every writer thinks their first novel is going to change the game. You have to have that kind of optimism to stay sane and get the work done. It drives you; it clarifies things for you, and then there’s something later on when you realize well, that’s not going to happen. I’m wrong. I was wrong about so many things. American Psycho. I knew I’d promised my publisher it was a novel about a serial killer on Wall Street, and that’s all I’d said. They gave me an advance. I didn’t have to show them anything. I mean, this is unheard of. It was a lot of money. I began writing it and it went through a lot of different iterations until I became really interested in this hallucinatory, pornographic, superviolent, surreal novel that they hated. I mean, they hated it when it came into the publishing house, but I thought to myself, OK, only 5,000 people are going to read this. I don’t care. I have to write it. I’m obsessed with it. I want to finish it. Then I thought, well, Glamorama is so commercial, I know that’s going to sell so many copies and it’s going to offset the failure of American Psycho. No. That did not happen. The opposite happened. So, what does a writer know? I don’t know. Luck, fate, talent? I don’t think about myself that way. I am the worst-reviewed writer of my generation. No other writer’s gotten as many bad reviews as I’ve gotten consistently for thirty-five years. From Less Than Zero onward. Bad reviews, no prizes, never winning an award, never invited to speak at colleges or invited to go to PEN or anything. I don’t have that association. So, when I hear a question like this, and I do hear it sometimes, there are writers who will ask me this, I go, “I guess, but it’s just not in my face. I mean, I don’t know it. I can’t feel it.” I mean, I certainly think I’m no Michael Chabon.

EN: You’re very loved though. People really do look up to you and your craft and your work.

BEE: It’s hard to see. One writer I really admire and that I wanted to have his career is Jonathan Franzen. Franzen has what I think I wanted.

EN: What is that?

BEE: He was able to do something that so many people had tried. He fused the postmodern novel with the technique and atmosphere of Don DeLillo, a writer of that generation we were all obsessed with. How does Don DeLillo achieve these effects? I tried with Glamorama. Jonathan was able to locate that and place it in a family novel about three kids trying to come home for Christmas, what The Corrections was about. He was able to fuse these two concepts together into something that spoke to so many people. And that’s where The Corrections is such an intensely important novel in the overall view of twenty-first century lit. He did it in a way that people responded to and loved. But I don’t really want to be Jonathan Franzen. I don’t want to sit around watching birds all day up in Santa Cruz. I don’t want to be that guy.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2023 World edition.