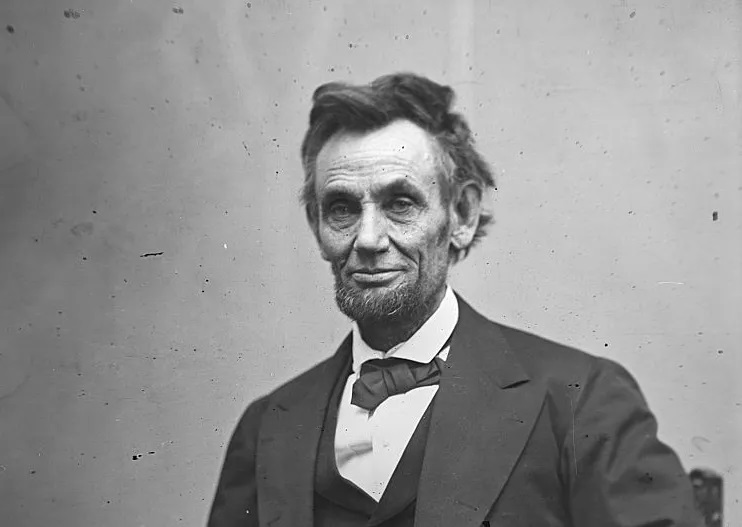

In an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times last week, filmmaker John Ridley urged HBO Max to remove Gone with the Wind from its platform. HBO Max capitulated right away, temporarily withdrawing the film until it can ‘return with a discussion of its historical context and a denouncement of [its racist] depictions’. As HBO weighs how to address what Ridley and others have described as the film’s romanticizing of slavery, I would encourage them to use the message of the movie itself as their guide.Gone with the Wind is about the perils of romanticizing. The movie begins with young men romanticizing the impending Civil War. ‘War! Isn’t it exciting, Scarlett?’ exclaims one of the Tarleton twins. With the women napping upstairs during a barbecue at Twelve Oaks, the men smoke cigars and confidently assert that ‘gentlemen always fight better than rabble’. When the war is announced, the barbecue erupts into cheers and music, as the partygoers rush outside, twirling their skirts and hats. Charles Hamilton runs up to Scarlett: ‘Isn’t it thrilling? Mr. Lincoln has called the soldiers, volunteers, to fight against us!’ Charles Hamilton will be dead two scenes later, catching measles and pneumonia before he ever sees a battlefield. The Tarleton twins will perish at Gettysburg. The throng of exuberant partygoers will be replaced by the throng of injured bodies stretching endlessly through the streets of Atlanta in one of the most iconic shots in cinematic history. Almost no man present at the barbecue will live to see the end of the war.The two men who do survive the war are the two who refuse to romanticize it: Ashley Wilkes, who observes that ‘most of the miseries of the world were caused by wars. And when the wars were over, no one ever knew what they were about’; and Rhett Butler, who warns that while the Yankees have factories, shipyards, coal mines, and a fleet, ‘all we’ve got is cotton, slaves, and arrogance’.These men, however, are wrapped up in the film’s most important storyline about the perils of romanticizing: Scarlett’s romanticizing of Ashley, at the expense of her relationship with Rhett. As Rhett comments when he first meets Scarlett after overhearing her begging Ashley not to marry Melanie Hamilton, ‘He doesn’t strike me as half good enough for a girl of your — er, what was it? — your passion for living.’ The remaining 200 minutes of the movie are spent proving Rhett right. Scarlett sulks over her fantasy of Ashley, as Ashley demonstrates time and again that he is unworthy — unworthy both of Scarlett’s adoration and of Melanie’s enduring patience. Meanwhile, Scarlett is blind to the love that the audience knows she deserves: Rhett’s. It isn’t until Scarlett sees Ashley distraught at Melanie’s death in the final moments of the film that she realizes her mistake: ‘I’ve loved something that didn’t really exist.’ She runs home to Rhett, only to find him packing his bags. She is too late, and frankly, he doesn’t give a damn.Gone with the Wind makes us love something that didn’t really exist: namely, what is described in the opening as ‘a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South’. With its mostly cheerful depiction of slavery, accompanied by breathtaking cinematography and arguably the best score ever written, the movie blinds us to the harsh realities of the American South. Like the young boys piping ‘Dixie’ while families read the list of casualties from the Battle of Gettysburg, the movie tries to soften with music that which cannot, must not, be softened.

[special_offer]

In other words, Gone with the Wind is guilty of the very thing it criticizes in its characters. It depicts the hazards of romanticizing, while itself being a romanticized depiction. But perhaps this is intentional. Perhaps Scarlett’s declaration that she has loved something that didn’t really exist is meant as a meta-cinematic warning: everything we have watched is also a fantasy, ‘no more than a dream remembered’, as the opening says. Rhett is revealed as the film’s truth-teller in more ways than one. ‘Cotton, slaves and arrogance’ — that’s all the South really was, and we mustn’t forget it.At the risk of romanticizing the romanticized, I’d like to think that this is the message of Gone with the Wind. We do not, then, have to work hard to criticize the movie; the movie criticizes itself. If the self-criticism is not sufficiently self-evident, then we can and should highlight it in our discussions. But it only speaks to the brilliance of this movie that after 81 years it still has the power to thrill us, move us, and infuriate us — and still leave us wanting more from it and from ourselves.