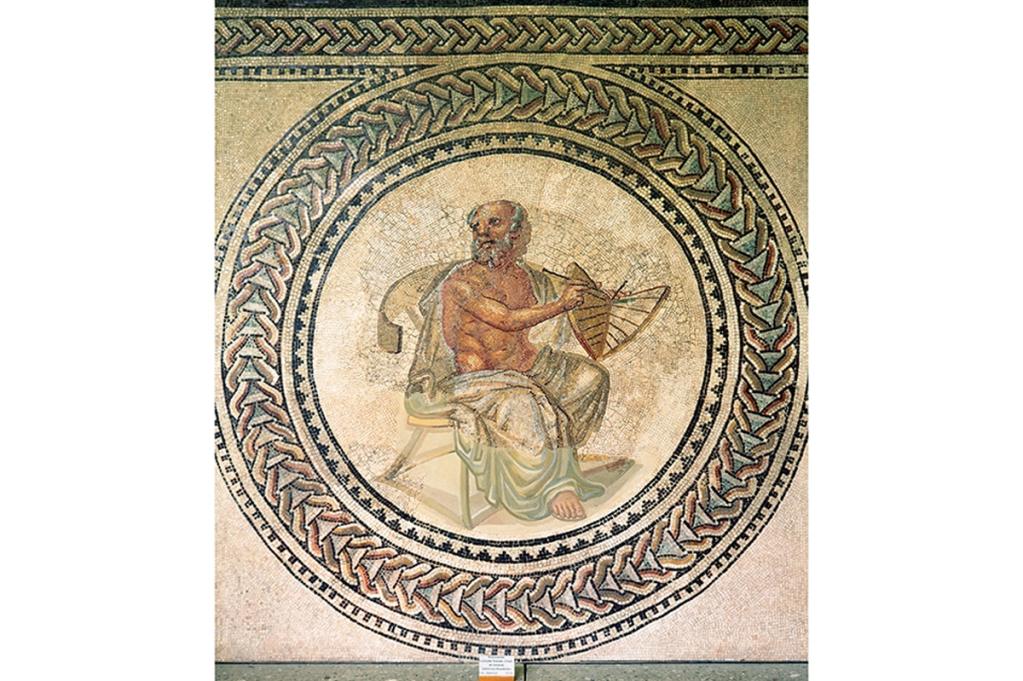

It’s a daring thing to write a whole book about a man while confessing early on that “we know almost nothing of his readings, life, character, appearance or voyages,” and of whose writings only a three-line fragment survives. Luckily, as with many ancient authors, the works of the sixth-century BC philosopher Anaximander are described in subsequent treatises, and a resourceful writer can infer much from this evidence about what might have been “the first great scientific revolution in human history.”

Anaximander, a Greek citizen of the cosmopolitan port Miletus, on the coast of what is now Turkey, was as far as we know the first human to say that the Earth was an object floating in space with no means of support (elephants, turtles, or what have you). Why didn’t it fall? Because there was no preferred direction in which to fall: it was indifferent to directions. (It would take millennia before it was understood that you could say the Earth is constantly falling around the sun.) So, in contrast to all other ancient civilizations, which pictured the heavens above and the Earth below, Anaximander insisted that the very ideas of “up” and “down” were relative.

The sole example of his own verbatim writing we have, meanwhile, from a treatise On Nature, is brief enough to quote in full.

All things originate from one another, and vanish into one another according to necessity; they give to each other justice and recompense for injustice in conformity with the order of Time.

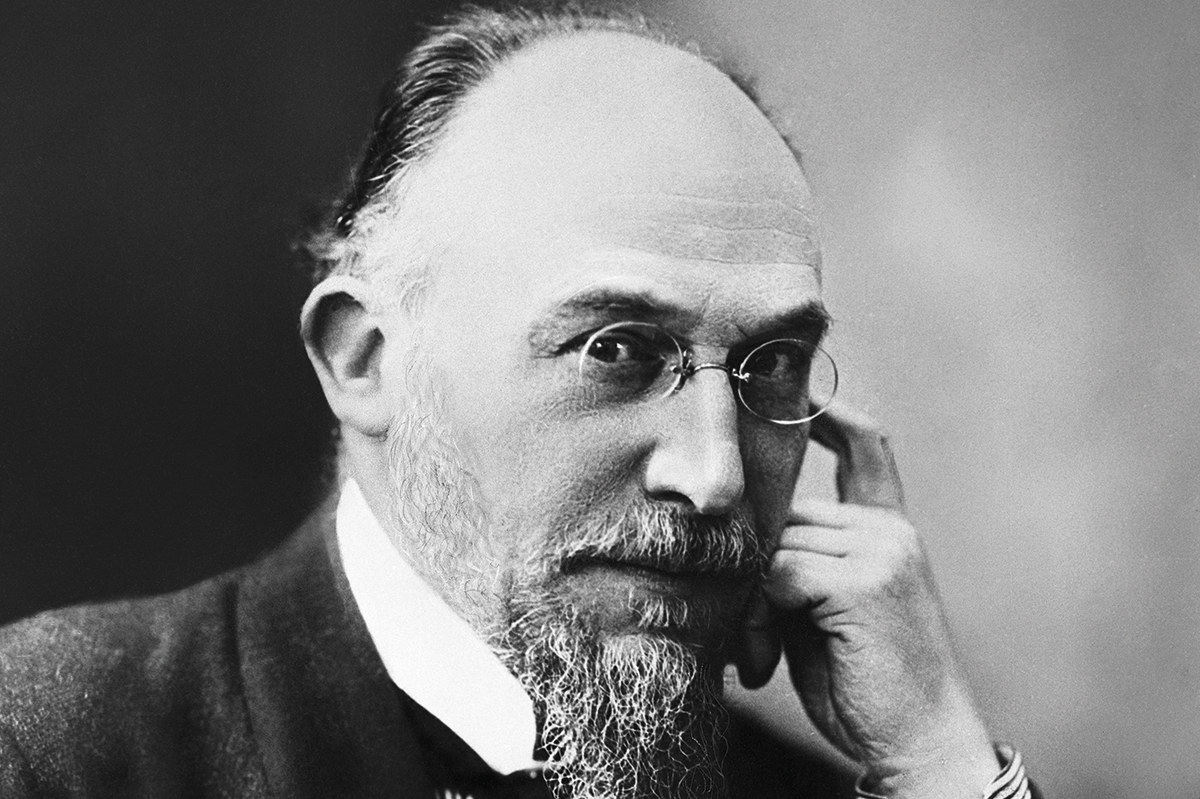

In Carlo Rovelli’s rather thrilling exegesis, this too becomes revolutionary, both in its positive claims — things happen out of “necessity,” so there is a causal order to the universe; all things are made up of more fundamental entities — and in what it signally refrains from saying: that any of this is controlled by the gods.

Indeed, according to later authors, Anaximander is also the first to give an entirely naturalistic explanation of weather, doing away with thunderbolt-hurling Zeus and chums. Rain, he says, is water that has evaporated from the ocean and been blown over the land. True! Perhaps most impressively, he intuited that, rather than having been divinely created, human beings must have evolved from earlier life forms and that the first life probably originated in the sea before crawling out on to land.

With this book, first published in Italian in 2009 and already published in English with a small US house in 2016, Rovelli is a long way from being the first to have noticed Anaximander’s importance. No less a luminary than Karl Popper called the Greek’s declaration that the Earth is a body suspended in space “one of the boldest, most revolutionary, and most portentous ideas in the whole history of human thinking.” But Rovelli is also addressing the present, mounting an energetic attack on the persistence of religious thinking, which on original publication at least might have caught the tail end of the new-atheism bubble but is not really necessary here to buttress his positive arguments.

His polemical theme, above all, is a laudable and passionate request that, as a culture, we navigate better between the Scylla and Charybdis of absolute scientism (the idea that we know everything for sure) and absolute relativism (the idea that all “ways of knowing,” as the pomo anthropologists have it, are equally valid). In contrast to the former, he pictures science as a ship of Theseus, of which every part is subject to change — yet still it floats. As a punchy counter-argument to the latter trend, meanwhile, Rovelli points out that when the Jesuits showed Chinese astronomers in the seventeenth century that the Earth was actually round, in contrast to their own traditional flat-earthism, they immediately adopted the idea: not because it was imposed by colonialism, but because they could see that it was true. So, too, he argues correctly that the scientific tradition kickstarted by Anaximander is not merely “western science” but the inheritance of the whole world.

Against the twentieth-century giants of philosophy of science, meanwhile, especially Thomas Kuhn and his The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Rovelli wants to emphasize unfashionable notions of progress in scientific history. In mathematics, for example, “the Babylonians developed the concepts that, in our time, are studied by seven-year-olds,” while science as a whole is more cumulative (and so reliable) than the expounders of abrupt theoretical change imagine.

Rovelli is himself a theoretical physicist as well as a bestselling popularizer of physics, and his wonder at his subject — science, he insists, is “visionary”; also “critical and rebellious” — is palpable, even unto a sort of Wittgensteinian mysticism. (“The very distinction between the world and our thought is an enigma,” he writes gnomically.) Which is not to say that the book ignores more earthly matters, as when the author lets his hair down and indulges in some sardonic punditry:

Each time that we — as a nation, a group, a continent, or a religion — look inward in celebration of our specific identity, we do nothing but lionize our own limits and sing of our own stupidity.

The cosmopolitan geniuses of the ancient world who began the systemic study of natural philosophy, one imagines, would have agreed.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.