Hearing about the death of Burt Bacharach at the age of ninety-four, I thought of one word: maestro. The word is variously defined as “a master, usually in an art” (Merriam-Webster) or “a man who is very skilled at playing or conducting” (Cambridge), but my favorite is the beautiful simplicity of the Longman definition: “Someone who can do something very well.”

The good (Brian Wilson: “He was a hero of mine and very influential on my work… he was a giant”), the bad (Billy Corgan: “A titan of beautiful and effortless song”) and the ugly (Mick Hucknall: “Farewell, genius”) of the music business spoke as one on this loss, with my favorite post coming from Noel Gallagher: “RIP Maestro. It was a pleasure to have known you.” There’s a gorgeous clip of these two great songwriters on stage together at London’s Royal Festival Hall performing “This Guy’s In Love With You,” and on the album sleeve of Oasis’s 1994 debut album Definitely Maybe a photograph of Bacharach appears.

After Bacharach’s death last week, the tributes poured in — but this wasn’t the usual irritating dog-whistle of mass mourning which led me to coin the phrase “tear-leaders” to describe groups of people competitively mourning dead celebrities on social media. This felt more like the death of the Queen: someone so familiar yet so mysterious, who we could measure our own lives and loves and losses against. Bacharach was a touchstone of what we most loved — and lost — about twentieth century American culture, the glorious like of which we will never see again.

He was a reminder that it was Jews of the USA — inspired by and alongside black Americans — who created popular music. Born in 1928, he said of growing up in a suburb of New York: “The kids I knew were Catholic… I was Jewish but I didn’t want anybody to know about it.” The teenage Bacharach got a fake ID in order to see the likes of Count Basie. Drafted into the army at twenty-two and stationed in Germany, he played the piano in officers’ clubs, doing the same in the Jewish resorts of the Catskill Mountains after demob. But the air of unimpeachable glamour that surrounded Bacharach started when, still only twenty-eight, he was hired by Marlene Dietrich as arranger and conductor for her international tours. He wasn’t only her employee, and she wrote: “Being with him was seventh heaven… as a man, he embodied everything a woman could wish for… how many such men are there? For me he was the only one.”

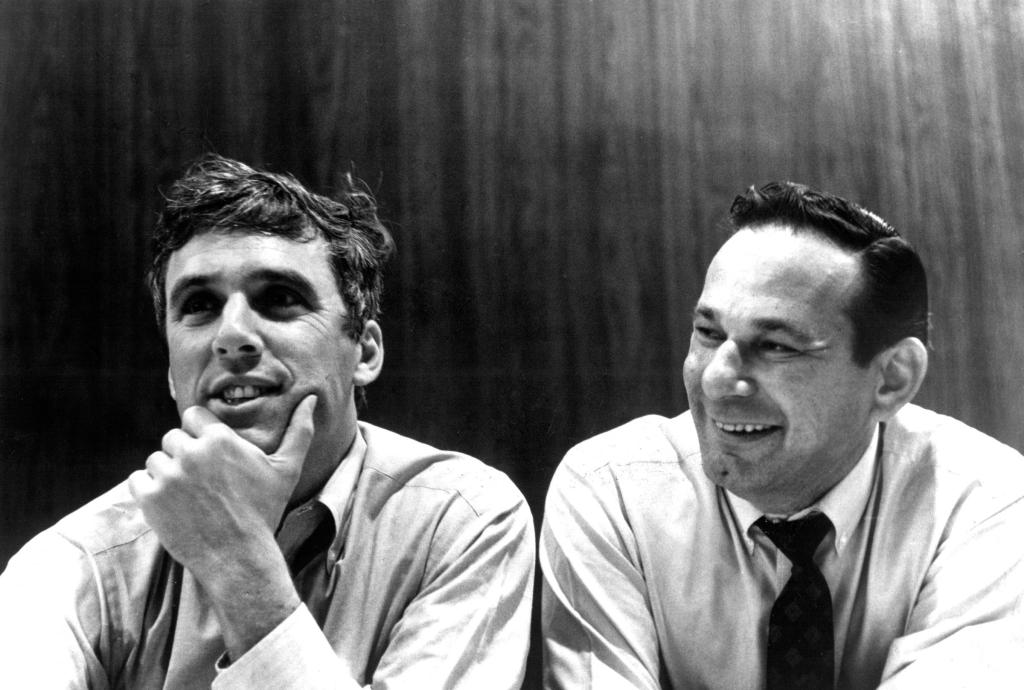

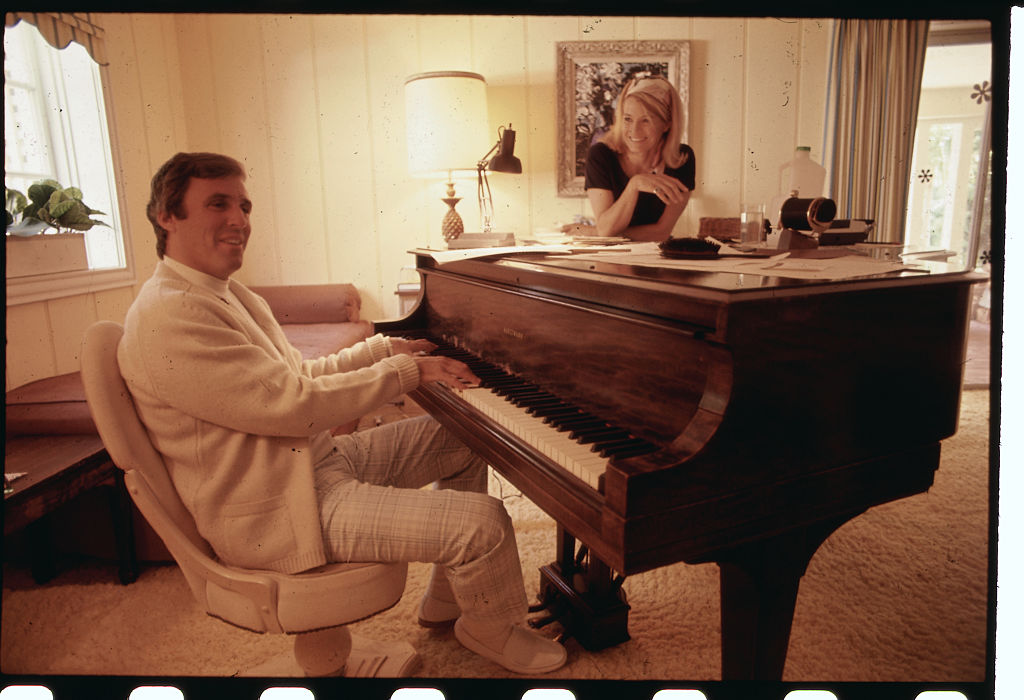

He was still in his twenties when he met the lyricist Hal David and they began their writing partnership. Bacharach and David were the last of the great silent songwriters — authors of songs who don’t believe that they’re necessarily the best person to sing them any more than a playwright should always act or a choreographer should always dance. They wrote best for women; Dionne Warwick was their ultimate muse but though their work with Aretha Franklin and Dusty Springfield was excellent, I have a soft spot for the Cilla Black interpretations.

She sang first his favorite of all his own songs, “Alfie”; turned down by Warwick and by Sandie Shaw, Bacharach wrote a letter to Black telling her that it had been written especially for her. Although she didn’t care for the song on first hearing — “Alfie? You call your dog Alfie! … [Couldn’t] it be Tarquin or something like that?” — rather than decline an offer from the world’s greatest living songwriter, she set the bar high: “I said I’d only do it if Burt Bacharach himself did the arrangement, never thinking for one moment that he would. [When] the reply came back from America that he’d be happy to… I said I would only do it if Burt came over to London for the recording session. ‘Yes,’ came the reply. Next I said that as well as the arrangements and coming over, he had to play [piano] on the session. To my astonishment it was agreed that Burt would do all three. So by this time, coward that I was, I really couldn’t back out.” Twenty-eight takes with a forty-eight-piece orchestra made it one of the most beautiful songs about the compulsion and confusion of love gone wrong ever recorded.

It’s always daft to attempt to refract the past through the standards of today, and anyone making a case for Bacharach and David being early feminists would have to explain away lyrics like “Wear your hair just for him / Do the things he likes to do” (“Wishin’ And Hopin’”). But they also created the beautiful and unusual (at the time) “Don’t Make Me Over” — ‘Don’t make me over / Now that I’d do anything for you / Don’t pick on the things I say, the things I do / Just love me with all my faults / The way that I love you.”

Their songs soundtracked a lovely time in America’s sexual history, the era epitomized by Rona Jaffe’s novel The Best Of Everything, after the pill but before the dirty hippies gave free love a bad name, when Nice Girls suddenly could Go All The Way without a red letter. When Penguin reissued the book in 2011, it came with a jacket quote by me: “It harks back to a saner time, when choosing progress and modernity was as straightforward as ordering dinner – ‘Two scotches with water on the side, and two steaks.’” The same is true of Bacharach and David songs.

These songs were extraordinarily sexy; Bacharach said in later life: “I remember sitting next to a woman on a flight a few years ago. She’d had a couple of drinks and she said: ‘Can I tell you something?’ I said: ‘Sure.’ She said: ‘I can’t make out properly unless I’m listening to your music.’ So that’s been my contribution.”

Though often playful, conjuring up Mad Men and three-martini lunches, other songs dealt with a very adult kind of love, the kind that could shatter hearts rather than provoke tears on a pillow — “Walk On By” — but could also somehow make the heart stronger on the breaks. Hearing it on the radio still sounds like a benediction, some sort of everyday miracle, reassuring even the most sorrowful lover that something beautiful can come out of something devastating.

Though his seemed a charmed life, Bacharach knew sorrow. In 2016, aged eighty-eight, he composed and arranged the song “Dancing with Your Shadow,” sung by Sheryl Crow and inspired by his daughter Nikki, who had committed suicide at the age of forty.

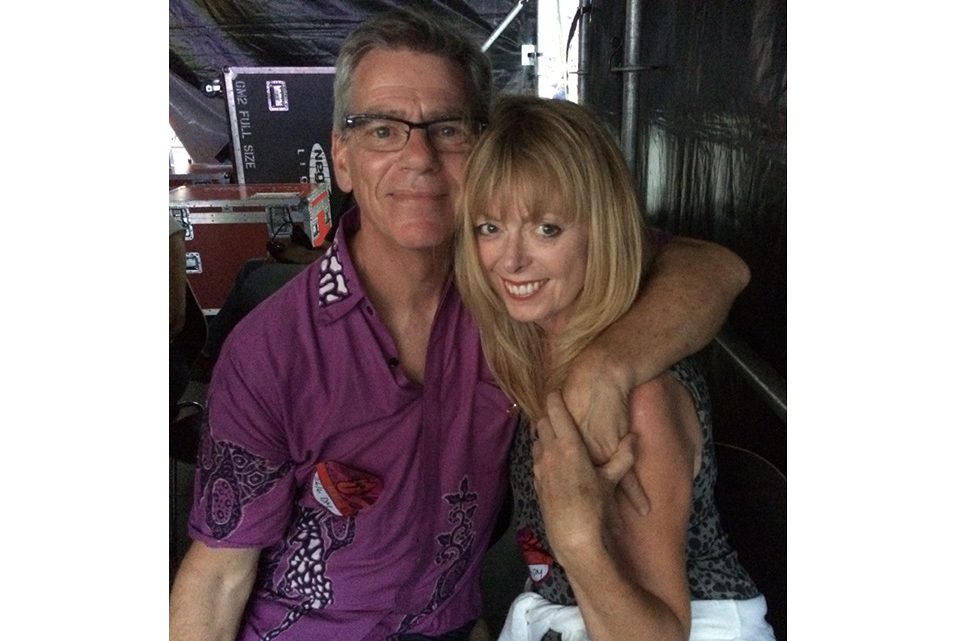

He aged well; much married, he seemed curious about new music but never desperate to be relevant. In 1998 he co-wrote and recorded a Grammy-winning album with Elvis Costello, later reuniting for Costello’s 2018 album, Look Now; next month another collaboration with Costello is due, expected to include songs from a proposed stage musical.

Like any writer who works a lot, Bacharach experienced failure. 1973’s soundtrack for the epic turkey Lost Horizon provoked a quarrel and lawsuits between Bacharach and David; the previous year, Dionne Warwick bizarrely — but successfully — sued Bacharach for his decision to stop working with her. His 1970s solo projects failed, even when he reunited with David to write and produce for Motown. But he could laugh at himself, with cameos in all three Austin Powers film, the trilogy which creator Mike Myers said was partially inspired by hearing “The Look Of Love” on the radio: “It was amazing working with Burt — it was like having Gershwin appear in your movie.” In an age when everything from sausage rolls to window cleaning is called “iconic” — “widely known and acknowledged, especially for distinctive excellence” — Burt Bacharach truly was.

Often when we mourn our heroes we mostly mourn for ourselves and our own thwarted dreams. The death of Bacharach is different. It marks the end of an era when the future looked bright and beautiful rather than the ceaseless drab cycle of outrage and apologies the twenty-first century is turning out to be. The songs of Bacharach and David are an epitaph for those lost sunlit decades when we really did believe that our future would outshine our past — when we really did live in modern times. Watching Sam Smith and Madonna make seven sorts of fools of themselves at the Grammys just three nights before Bacharach died, the contrast between the pinnacle of popular music then and now was surreal. The Age of Accomplishment is gone — welcome to the Age of Attention-Seeking, which will leave us all the poorer. RIP, Maestro.

This article was originally published on Spectator Life.