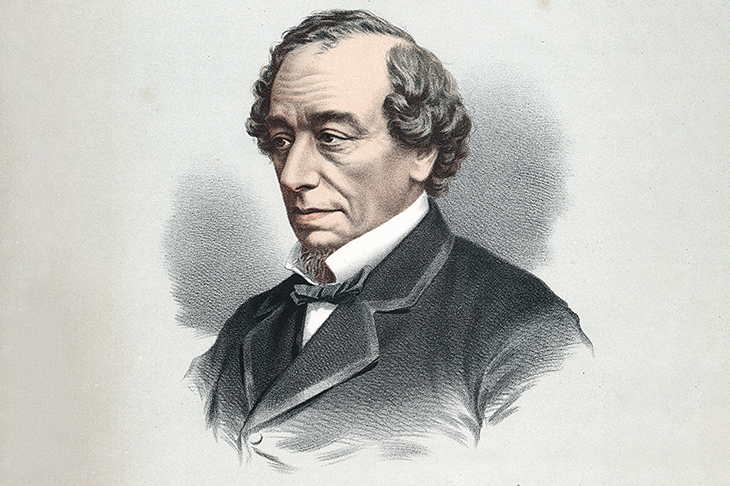

For our fractured times, the release of Disraeli’s Sybil in unabridged audio, narrated with the respect it deserves by Tim Bentinck, is timely as, despite its title being familiar, these days it is seldom read. Published in 1845, 23 years before Disraeli’s first premiership, the story, rich in the minutiae of then contemporary political conflict, covers the years of reform and unrest between 1837 and 1844, but throws up startling parallels between then and now.

The young agitator Stephen Morley speaks directly to us. There’s no community in England, he says; city men are united only by their desire for gain, not in a state of co-operation but of money-seeking isolation. Did Brexiteers vote, as did the Chartist Walter Gerard for the People’s Charter, not for the ‘reforms & remedies’ but merely because they were ‘a change’? Hard-pressed laborers resent the ‘himmigrants’ from Suffolk beating down their already meagre wages and, concerned for the future by the increasing population, Gerard asks Charles Egremont: ‘How will you feed them? How will you clothe them?’

Egremont, Disraeli’s protagonist and mouthpiece, is the younger brother of Lord Marney, the savagely unfeeling aristocrat who is content for his tenants to survive — or not — on seven shillings a week. Egremont lodges for a while in the north of England in order to witness the dire conditions of the poor, where he meets Gerard and his daughter Sybil. In reply to Egremont’s boast that Victoria reigns over the ‘greatest nation’, Disraeli gives Gerard the novel’s stand-out lines. She reigns, he says, over two nations:

‘between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy, who are ignorant of each other’s habits, thoughts and feelings as if they were dwellers in different zones… THE RICH AND THE POOR.’

In further illustration is the desperate hand-loom weaver, working with no fuel, food or furniture, his sick wife and children lying in the one wretched bed as effluent leaks across the floor and a common midden heap putrefies outside. Another is seen in the tilting hovels amid the ruined mineshaft landscape, as the ‘swarming multitude’ of men, women and little children, condemned to long days in the bowels of the earth, are disgorged from darkness into darkness. Such images of the degrading inhumanity of poverty are the strengths of Sybil, justifying its description as the first state-of-the-nation novel.

As a work of fiction, however, it’s deeply flawed. Two-dimensional characters are mere mouthpieces for Disraeli’s polemic. As for Sybil herself, she is first glimpsed by Egremont as a novice Catholic nun and remains sublimely seraphic (although I do wonder about her ‘undulating and elastic figure’). Despite their burgeoning love, the ‘impassable gulf’ of social class keeps them apart.

Disraeli had started writing much earlier, hoping to recoup at least some of the disastrous losses he had incurred in South American mining shares. And he was clearly in a hurry to get Sybil finished. Suddenly years have passed in the novel, and violent, drunken rioters begin attacking Castle Mowbray. Lord Marney is stoned to death, and Gerard is killed as Sybil cowers in ‘frantic terror’. Out of nowhere, bloodstained, saber-wielding Egremont arrives and throws his strong arms around her, promising: ‘We will never part again!’ Then, within a few lines of Sybil’s murmured agreement, she has returned from a year-long honeymoon in Italy, having been found, by way of that stock device of Victorian novel-writing, entitled to the Mowbray estates and £40,000 a year.

It is clear that Disraeli believed a paternal, benevolent aristocracy would, through democratic government, create one nation; but the ending of Sybil does not provide anything approaching a resolution to the conflict. This he leaves to the ‘Youth of a Nation, the trustees of Posterity’ in his brief and unconvincing authorial envoi. Perhaps at that stage he could pose the problem, but was not able to resolve it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.