It’s December 2020, in the middle of the pandemic, and Kara Swisher has invited Jason Kilar, CEO of Warner Bros onto her New York Times podcast, Sway. Kilar has just announced that his company will be breaking its theatrical windows, simultaneously releasing their full slate in cinemas and on their streaming service, HBO Max. Swisher sees him as the first CEO pushing ahead into an obvious streaming future, without cinemas. In Swisher’s words: “I’ve said movie theaters are dead men walking… their bad popcorn, their idea of innovation is a comfy seat; this [COVID] is just accelerating a trend that’s already been happening.”

Her argument is simple: why spend the money to go out, and bring the family to a cinema, when you can watch it in your living room?

In January 2020, Netflix stock was $330. By November 2021, it was almost $700, having grown by more than 230 percent in under two years. Venture capitalists were convinced. Hollywood executives were convinced. Kara Swisher was convinced.

They were all dead wrong. And the Barbenheimer bomb eviscerated any remnants of those ideas.

With Barbie and Oppenheimer, two auteurs took premises unlikely to produce novelty and greatness — namely, a toy commercial and an Oscar-bait biopic — and made films as successful commercially as they were artistically. Their release was the first time in cinema history that two films grossed more than $80M on the same opening weekend and was the fourth highest grossing weekend ever.

Ironically, Oppenheimer only exists because of Kilar’s streaming decision. Nolan had made all of his previous films with Warner Bros, but was outraged by Kilar’s turn away from the cinema and began taking meetings with other studios in July 2021. Universal gave Nolan his desired budget, and enormous 100-day exclusive theatrical window. In return, he gave them more than $265 million in a week, and – presumably – Oscar nominations and wins down the road.

Meanwhile, the streaming future predicted by Swisher et al is withering. Five days after this blockbuster weekend, NBCUniversal announced that their streaming service, Peacock, had lost $651 million between April and June. That’s less than in Q1, when it lost $704 million, but it’s still not great. This year, they expect “peak” losses on streaming to reach $3 billion. Meanwhile, Netflix is back down to $425 a share, and Warner Bros renamed HBO Max to “Max,” and has lost much of their good will.

This is all happening as writers and actors are on strike over concerns about pay and the use of AI tools; Chinese audiences have stopped rewarding Hollywood studios for their bootlicking; and “guaranteed” franchise blockbusters have bombed. The movie business is at a potential turning point, where confident predictions about the consequences of technological change have been disproven, long-standing tensions have turned into standoff, and the future of cinema is up for grabs.

With the advent of the internet, many executives and investors thought the classic cinema model was outdated. Why use film when you can shoot on digital? Why shoot it on set if you can “fix it in post”? And if you can use AI and deep fakes to bring an actor back from the grave, or reshoot a scene, or de-age an actor, what harm is there in using that technology? Who cares if it costs more, or is disrespectful, or looks terrible? It’s convenient, and innovative!

Prior to the internet era, studios released a full slate of mid-budget films, and though many would only break even, or even lose money, a few would be huge hits, which covered for the rest of them. But the internet meant that, instead of releasing the low and mid-budget films, studios would sell these films to home audiences. If these were hits, they didn’t have to share revenue with cinemas; but if they flopped, nobody would notice. Bundle these films together as a streaming service, and they had the recurring revenue stream that investors love.

This also meant that studios could limit their cinema releases to those “guaranteed hits,” like superhero films, and juice up their budgets so the films were big as possible. They would earn billions, instead of just hundreds of millions, and by releasing fewer films, studios could also squeeze cinemas for a larger cut of ticket prices.

This seemed less risky, and it worked – until it didn’t. The huge budgets meant blockbusters had to be as widely acceptable as possible. They couldn’t be too weird, or have style that some audience members might not like, or address themes that were challenging. There couldn’t be any sex, the violence had to bloodless, and they couldn’t offend the Chinese. By filming almost entirely on green screen, they could also be endlessly tweaked and changed by producers. The net result was blandness. No wonder customers eventually realized there wasn’t much point in going to see them in cinemas. Why should audience see them in cinemas then? In the last year, they haven’t.

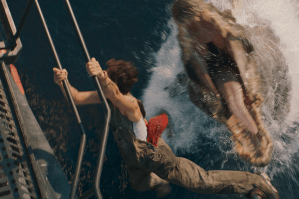

Shazam! Fury of the God flopped. Ant-Man and The Wasp Quantumania failed to break even on it’s $200 million budget. Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny has done even worse on a production budget of $300 million. The only superhero films to release in the past year that were big commercial hits were Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 and Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. Not coincidentally, they were also the only creative, aesthetically interesting superhero films released in that period. Barbenheimer was such a success because these were real, bold, original films.

In that Swisher interview, Kilar said of the change that, “You can’t go through a pandemic like this and have things go back to the way they were in 2019.” That’s true; but how things change is up for grabs, and there’s never been a moment more primed for a status quo shift; hopefully, for the better.

This isn’t to say that for Hollywood to make hits again, they should fire all the accountants, toss out CGI, and give artists free reign. 1970s American independent cinema was a golden age of creative freedom, but it was that lack of restraint that killed it. Studio executives sat by as Michael Cimino spent $44 million dollars (in 1980 money) on a boring, terrible epic. It only grossed $3.3 million dollars, and killed United Artists, it’s distributor.

Moviemaking is at its best when the commercial and the artistic, the real and the fake, go hand in hand. China is an unlikely example of where this still works today. Unbeknownst to most Western cinema goers, China is in a cinematic golden era, with home-grown productions outgrossing Western films. Part of this is state-sponsored jingoism — after all, the top hits remain “Wolf Warrior” state propaganda action films — but their local film economy is closer to 1980s Hollywood than that of today, with a range of original rom-coms, thrillers and comedies bringing audiences to cinemas, and succeeding with it.

If studios want to return to the Golden Days, and make Barbenheimer the norm, they could put guiderails in place for the use of AI, increase payouts to actors, writers, and directors on streamed properties, and reallocate their finances towards mid-budget films, with real stunts and effects, made by distinctive artists. If film studios give new directors modest to medium budgets to make new properties, and those artists use AI to speed up their production pipeline, we could have a renaissance of independent film-making (particularly science fiction); and it would earn studios billions.

Then again, Hollywood is stubborn. Rather than come to the table and end the strikes, studios are choosing to lose momentum, and push films until next year. Some of this is excuse making — it seems nobody at Sony thought the next Spiderverse film had any chance of releasing next March, so the push wasn’t really prompted by the strikes. Some of it isn’t though.

Similarly, as critic Sonny Bunch told me, production times are long and this reversal to quality “could easily be upended in a couple of months if The Marvels grosses a billion dollars worldwide and Killers of the Flower Moon grosses three hundred million. No one knows anything.”

Maybe Kara Swisher will be proven right in the end, and Hollywood won’t change. Maybe they’ll keep pumping out crap, cinemas will close, and content will get more generic and disposable. I hope not that though. And if Hollywood is going to change for the better, now is the time.