In 2011, a terminally ill Christopher Hitchens faced death with droll stoicism: “To the dumb question ‘Why me?’ the cosmos barely bothers to return the reply: ‘Why not?’” he wrote. As his health declined and the end drew nearer, the skeptical Hitchens stuck to his atheist guns, clear-eyed in his confidence that death was final.

Hitchens died in 2011, but his work and reputation live on. No paradox there, of course, but just how large Hitchens looms twelve years after his death would surely have surprised even this immodest author. It’s certainly a surprise to me, a reformed Hitchens fanboy. The face of twenty-first-century atheism is having quite the afterlife.

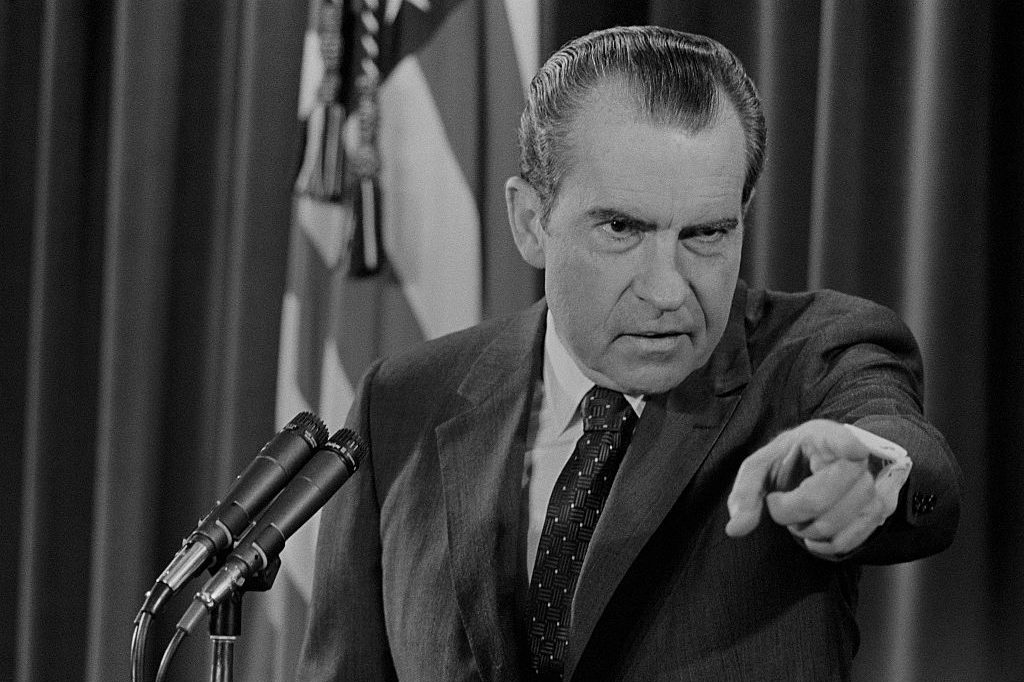

Hitchens was a famously prodigious writer, and his publishers have been just as busy in the decade after his death. Essay collections have been assembled and reassembled and published posthumously. Twelve of his works were reissued by Atlantic Books in 2021, including his famous hit-jobs on Bill Clinton (No One Left to Lie To), Henry Kissinger (The Trial of Henry Kissinger) and Mother Teresa (The Missionary Position).

On social media, fan accounts churn out a steady reissue of Hitchens witticisms, usually accompanied by a picture of a ruminative looking Hitch puffing on a cigarette or holding a glass of whisky (“Mr. Walker’s amber restorative”). Also on the feed: writers who call Hitchens a friend (some, I suspect, with weaker claims than others) lamenting his missing voice in a given debate: he would agree with them, of course, but make their point more eloquently.

Then there are the books trying (and mostly failing) to do unto the Hitch what the Hitch did to others. Among them: God is Great!, The Rage Against the Light: Why Christopher Hitchens was Wrong, Unhitched: The Trial of Christopher Hitchens. Maybe the most dishonorable contribution to the Books About Hitchens shelf is The Faith of Christopher Hitchens, the 2016 work by evangelical author and Hitch’s occasional theological sparring partner Larry Taunton, in which he suggested that Hitchens’s atheism was shakier than it seemed.

In 2021, there was another fuss about Hitchens’s legacy; his widow, the poet Carol Blue, and his agent, Steve Wasserman, wrote to his friends to warn that “a self-appointed would-be biographer, one Stephen Phillips, is embarked on a book on Christopher,” and urging them not to cooperate. There is still no sign of Pamphleteer: The Life and Times of Christopher Hitchens. Not that Hitchens obsessives had to wait long for their next fix: 2022 brought Christopher Hitchens: What He Got Right, How He Went Wrong and Why He Still Matters by Jacobin columnist Ben Burgis. This year, we have Matt Johnson’s How Hitchens Can Save the Left: Rediscovering Fearless Liberalism in an Age of Counter-Enlightenment.

Faced with this growing pile of Hitchenalia, the obvious question is “why?” What is it about Hitchens that makes him the subject of such fascination? In the case of Johnson’s recent plea for the left to rediscover its enlightenment values, why not How Voltaire Can Save the Left or How Orwell Can Save the Left? Adding to the mystery is the fact that Hitchens’s preoccupations — proselytizing atheism, nation-building in Mesopotamia and opposition to “Islamofascism” — have slipped off the agenda. And Hitchens, though he left a mountain of great journalism behind, never wrote a truly great book.

Part of the answer is simply Hitchens’s talents: whether onscreen, onstage or on the page, his sharp wit, intellectual dexterity and encyclopedic recall made him a must-watch and must-read public intellectual. Another is his ideological journey, from Trotskyist agitator to liberal hawk and close pal of Paul Wolfowitz. There’s something for almost everyone there.

But one morbid and under-appreciated factor at work here is timing. His departure was recent enough for Hitchens to still seem of our time but long enough ago for him to feel removed from the debates that dominate the present. Hitchens died before the so-called Great Awokening that bubbled up in the mid-2010s, before the discombobulating events of 2016 and long before the pandemic. Admirers can construct an idealized version of the Hitch rather than grapple with the disappointment of finding him on the other side of a given issue.

Timing matters when it comes to medium as well as message. Hitchens was at the peak of his fame when every television appearance, from blockbuster public debates to late night C-SPAN phone-ins, could be uploaded to YouTube. The site is stuffed full of “Hitchslaps”: highlight reels of his put-downs and owns are well-suited to a younger generation with internet-fried attention spans. He was gone before the media landscape splintered, before Twitter and Facebook became the primary forums for public debate. Social media, with its flattening effect as well as its opportunities for oversharing and its tsunamis of ill-judged and uncharitable jibes, has vaporized the mystery and glamor that once surrounded writers and public intellectuals. It’s hard to imagine a writer today being as cool as Hitchens undeniably was. But then maybe I’m overthinking it. Why Hitchens? Why not?

This article is taken from The Spectator’s June 2023 World edition.