We’re in Virginia, in the 1850s. A girl called Emily is tormenting her dog, Champion, and her father’s teenage slave, Rawls. Seeing this, Emily’s father, Bob, beats her with his belt and kicks the dog. Of Rawls, Bob says: ‘Now leave him be so he can get about my business!’

A girl, a dog, a slave, and a slave-owner.The owner addresses the girl with words and violence, and abuses the dog. He helps the slave get down from the fencepost he’s standing on. But he does not talk to the slave. He talks about the slave.

Thinking this over, Rawls looks at Emily,‘sprawled out and wailing in the grass’, and envies her. Her pain is temporary; his is permanent. ‘Tomorrow she would leave the house, and pain would be as incomprehensible to the girl’s mind as the map of a foreign country in a schoolbook. He had found no boundary to his own.’

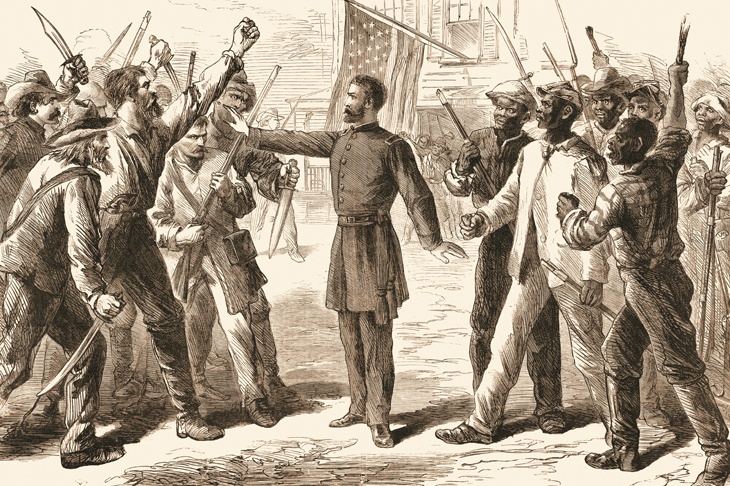

In his first novel, The Yellow Birds, Kevin Powers, a veteran of the Iraq war, wrote about violence and its consequences. He can evoke pity in the manner of Wilfred Owen, although he adds something more contemporary, a new type of guilt, to the pity. This novel communicates some of the same emotions, but it’s more panoramic. Here, we are taken through the American Civil War and beyond, to the 1980s, when somebody who knew somebody who knew Rawls dies a sad death in a hospital bed.

Emotionally, we are with Rawls all the way. Early on, we find out that a previous owner had ‘had to dock his toes’ when he was a youngster to stop him running away. Later, he falls in love with Nurse, a female slave who suckles white babies. But it’s hard for Rawls to see much of her because they have different owners. Soon we learn that Nurse has been sold to the notorious Lumpkin, who is actively sadistic; later she will be owned by Levallois, a ‘queer Frenchman’ whose nastiness is of a different order.

There is lots of gore, and the sort of casual violence that can be just as disturbing. The book is also soaked in symbolism — cracked spectacles, a river crossing, an old mansion burned to the ground. There’s a scene in which two badly wounded soldiers, a blue and a grey, say a few words to each other. One of them can see his own severed arm, the fingers pointing towards him.

A Shout in the Ruins reminded me of Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain. You get a sense of sweeping sadness, and the odd dash of hope. And I think it too will be a film.