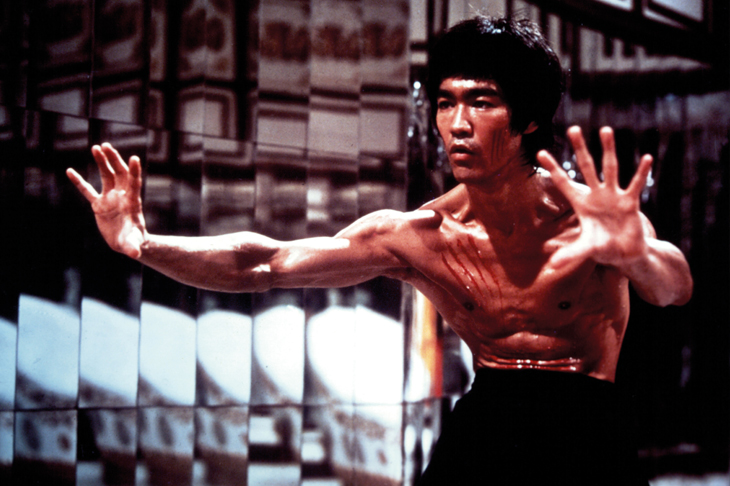

Every cinema-loving person has a favourite Bruce Lee moment. My own comes towards the end of Enter the Dragon, the film which Lee made just before his death in 1973 at the age of 32, and that would in turn seal his worldwide stardom. There, on one side, stands Lee himself. There, on the other, is the villainous Han, who has a set of metal talons where one of his hands ought to be. The two men leap across each other, leaving Lee with an unpleasant gash on his shirtless torso. He pauses, dabs a finger in the blood, raises it to his mouth — and licks. It is weird, gruesome and oh-so-cool, all at once.

Why did Lee do this? The answer is in Matthew Polly’s biography. One of Lee’s disciples had performed exactly the same move during a bar-room scrap and, unsurprisingly, found that his opponents were rather unnerved by it. As Polly writes: ‘Bruce loved the story and adopted it into his repertoire.’

Indeed, almost all answers can be found in Polly’s book. It’s a weird feature of Bruce Lee studies that, since his death, so much of the literature has been written by people who knew him, and so little has been written in the spirit of proper biographical investigation. Polly corrects that. He has devoted six years to researching his subject, but there were many additional years of effort before that. In his twenties, Polly left Princeton to develop his kung fu skills at the Shaolin Temple in China, and wrote a very funny book, American Shaolin, about the experience. He approaches Lee as a fan, but also as a scholar.

The scholar has a lot to unpick. Despite the pop simplicity of Lee’s image, emblazoned across a million posters and T-shirts, there is almost nothing about the man that is easy to summarise. His screen career took a twisty route through childhood dramas in Hong Kong, short-lived television shows in America, periods of great hyperactivity and of terrible inactivity, until it arrived at The Big Boss (1971) and the action films that brought him immense fame. His personality could be as threatening as it was charming. And as for his background, I’ll leave that to Polly: ‘Five-eighths Han Chinese, one quarter English, and one eighth Dutch-Jewish.’

But this is the point about Bruce Lee (and it is a point that saturates the pages of Polly’s book): he brought all of his parts together into a whole. Nothing was wasted. Even the cha-cha championship that he won as a teenager would eventually show in his fighting. ‘There was a sort of innate balance and rhythm within all his [movie] fights,’ the director Michael Kaye is quoted as saying, ‘and he was constantly looking for ever more complicated rhythms.’

Lee was a crossover star — crossing over disciplines, borders and prejudices — at a time when there were few, if any, others. In this respect, he was apart from his age; more like a cosmic intruder from our own. And yet he was also a part of his age and of its upheavals. One of the triumphs of Bruce Lee: A Life is how it operates as a history book, covering everything from the patterns of Chinese migration to the atrocities of the Manson family. I hadn’t known that Lee attended the funerals of two victims on the same day: Sharon Tate, whom he had trained for a film, and the hair stylist Jay Sebring, who introduced him to Hollywood.

Tellingly, the book loses some momentum when Lee is no longer an active part of it. A chapter about the inquest into his death becomes a catalogue of different witnesses’ testimonies — but, given that Polly presents a new and very plausible suggestion for the cause of Lee’s fatal cerebral edema, this departure from the book’s easy flow is probably a necessary one.

Besides, this is a book about Lee’s life rather than his death. From his early street fights to his friendship with Steve McQueen, from his cha-cha to his one-inch punch, Bruce Lee was made to be Bruce Lee. And Matthew Polly was made to be his biographer.