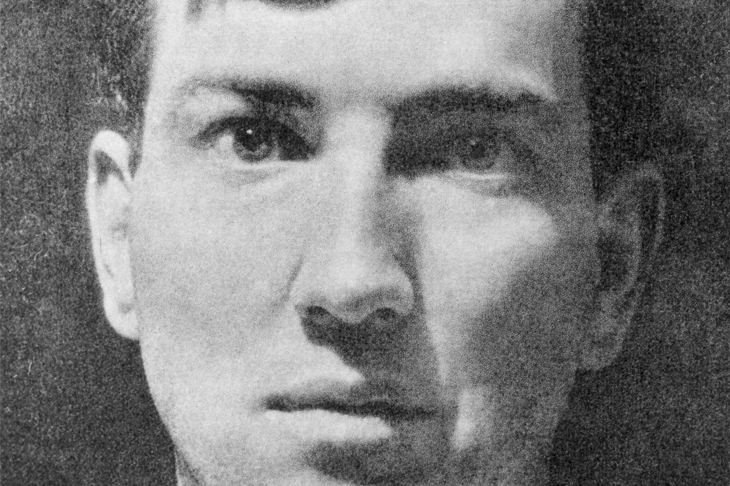

‘I have a very poor opinion of other people’s opinion of me — though I am fairly happy in my own conceit — and always surprised to find that anyone likes my work or character.’ This admission by Robert Graves — made to his then friend Siegfried Sassoon in the mid-1920s — goes to the heart of his character as a man and a poet. It projects a powerful mixture of defiance and neediness, which in his personal life produced a series of highly disruptive assertions and reversals, and in his writing life an equally striking set of commitments and walkings-back.

Jean Moorcroft Wilson, who has previously published fluent biographies of Sassoon and Edward Thomas, is a reliable guide to all these contortions. Her book tells only the first half of Graves’s story, but adds a valuable degree of detail to the several existing biographies and, thanks to the sympathy it shows for all aspects of Graves’s character, is consistently illuminating.

Right from the start Graves was conscious of his own dividedness. His mother’s Irish origins and his father’s German background may have created for him a childhood in which the prevailing mood was ‘earnest, religious and worthy’, but it also stimulated a sense of deracination — and even (when he became the butt of anti-German feeling in the years leading up to the war) of being unwelcome.

Graves’s response was to combine attempts at fitting in (learning English manners at the six prep-schools he attended in the first seven years of his education, then polishing them at Charterhouse) with acts of rebellion. His expertise in boxing, of which he later made a good deal in Good-Bye to All That, is a good example. It both earned him the respect of those he wanted to respect him, and was by its nature a proof of aggression.

The war, which broke out more or less exactly as Graves left school, was (among other things, of course) a gigantic theatre for his various kinds of ambivalence. Describing himself in 1917 as ‘a sound militarist in action, however much of a pacifist in thought’, he also turned out to be, during his years in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, a person of unusual sensitivity to suffering who was also capable of bombast and considerable bravery; a sexually shy prig who was nevertheless given to idealistic crushes on other men (he had previously been given to similar feelings for other boys at school); and an original thinker about poetry who was wide open to the influence of others.

Like the majority of poets in what became known as the Georgian generation, Graves was keen to shake off the glitter and dust of 19th-century versifying, and to adopt a more ‘realistic’ approach to things. When he made friends with Sassoon, who was serving in the same regiment, his work took a long stride in the direction he wanted — not so much because, in the early days of their friendship, Sassoon was that far ahead of him (in fact, as Moorcroft Wilson points out, it’s likely that Sassoon learned a few tricks from Graves), but because they reinforced an idea of simplicity in each other. Characteristically, however, where Sassoon trains his sights on brutally bare descriptions of trench warfare, gas attacks, the incompetence of generals and suchlike, Graves takes a more binary approach.

The poems in his first two books, Over the Brazier (1916) and Fairies and Fusiliers (1917) — how’s that for a title which shows someone in two minds? — do certainly contain all the horrible facts; but at their most successful they react to them by adopting a child’s point of view and language, or by glancing aside to childhood events and scenes. (In what Moorcroft Wilson calls his ‘first truly realistic war poem’, for instance, which ends with a reference to ‘sunny cornland where/Babies like tickling, and where tall white horses /Draw the plough leisurely in quiet courses’.) The result, especially when combined with the classical paralleling that Graves also favoured, is poetry of greater linguistic complexity, more elaborate technical expertise, and more finely tuned sound effects than much of what Sassoon aimed to produce, but less immediately explosive power.

When Graves was wounded at High Wood on the Somme in July 1916 he was announced in the casualty lists as being dead — only to recover and return to England. Although it would be hard to measure such a feeling accurately, this sense of being a revenant probably affected him for the rest of his life. It certainly appears to have determined his later decision to suppress a great deal of his war poetry — by making him seem to some degree unreal to himself, and so doubting the value of his witness.

It also, by promoting a curious combination of devotion and dissociation in his sensibility, seems to have given a governing shape to the marriage he made shortly before the war ended — to Nancy Nicholson, with whom he had four children. For the same sort of reasons it even more decisively affected the life they subsequently shared with Laura Riding in a ménage à trois that, before it finally and notoriously ended with Riding and then Graves jumping out of windows in a flat in Hammersmith, became briefly, with the poet Geoffrey Phibbs, a ménage à quatre.

Moorcroft Wilson does well to combine her account of these shenanigans with the other important aspects of Graves’s life: with his relationships with Sassoon and T. E. Lawrence; with his evolving literary ideas (the fiery critical books, and the expertise they demonstrate for close reading of poems, which William Empson was to acknowledge as an influence on Seven Types of Ambiguity); with his attempt to earn his living as a shopkeeper outside Oxford, and as a teacher of English in Cairo; and with his creation of his most famous book, Good-Bye to All That, which in its careless way with facts cost him his friendship with Sassoon. But simply because they are so strange, the circumstances of Graves’s life with Riding dominate all other elements.

Moorcroft Wilson allows us to understand that despite Riding’s craziness (her ‘great secret’ she told Graves, was that she was ‘going to stop TIME’), he needed her. He needed her to expunge his original puritanism, to extirpate, in so far as they could be extirpated, his memories of the war, and above all to help him evolve a system (later manifest in The White Goddess) that he could use as a way of controlling the whirling opposites he contained.

In the closing pages of the book, we see Graves and Riding living alone together in Majorca, with money in the bank, thanks to the success of Good-Bye to All That, swaying in a precarious balance for which they have paid a very high price in terms of friendship with others. We also understand there’s not a hope in hell it will last. Cue volume two, which Moorcroft Wilson says she looks forward to writing, and we should look forward to reading.

This article originally appeared in The Spectator magazine.