For tens of thousands of years, humans have been domesticating other mammals — cows, buffaloes, sheep, goats, camels, llamas, donkeys, yaks, horses — and keeping them for their milk. This has generated myriad products, from yoghurt and buttermilk through butter and cheese to toffee and ice cream, in many varied, culturally specific and resourceful forms. A sign of the elemental importance of this foodstuff is that our galaxy is called the Milky Way — and indeed the word ‘galaxy’ is derived from the Greek word for milk, gala. In Ancient Greek mythology, the Milky Way was formed when Hera, the goddess of womanhood, spilled milk while breastfeeding. Each drop became a speck of light, known to us as a star.

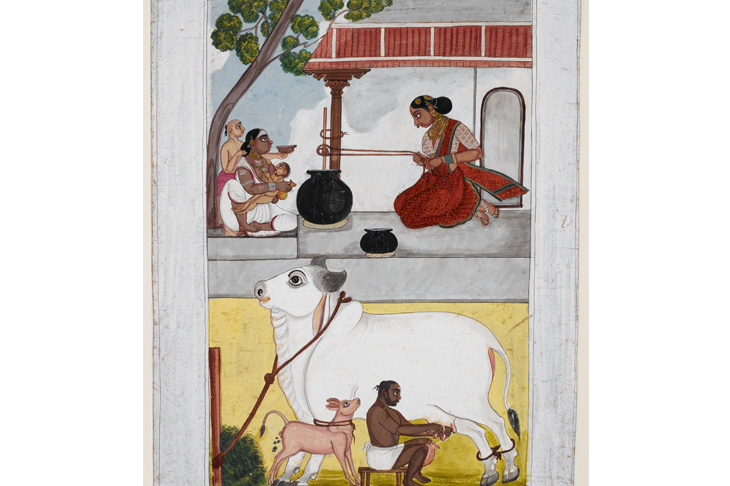

As the distinguished food historian Mark Kurlansky tells us in his arresting new food history, numerous cultures around the globe have milk-based creation myths. The Fulani people of West Africa believe that the world started with a huge drop of milk from which everything else was created. According to Norse legend, in the beginning there was a giant frost ogre named Ymir, who was sustained by a cow made from the thawing frost. From her teats ran four rivers of milk that fed the emerging world. The significance Hindus see in cows has a simple logic: cows give milk, milk sustains life, cows give life. Ancient Middle Eastern cultures figured out how to sour milk deliberately to preserve it in hot climates. Yoghurt is still so central to Persian culture that in modern day Iran, the idiom for ‘Mind your own business’ translates as ‘Go beat your own yoghurt’.

Back in 1861, in her Book of Household Management, Mrs Beeton advised her readers on the distinctive characteristics of mammalian milks:

Milk of the human subject is much thinner than cow’s milk; ass’s milk comes the nearest to human milk of any other; goat’s milk is something thicker and richer than cow’s milk; ewe’s milk has the appearance of cow’s milk and affords a large quantity of cream. Mare’s milk affords more sugar than that of the ewe; camel’s milk is employed only in Africa; buffalo’s milk is employed only in India.

These days, cows’ milk is the most commonly encountered, since cows produce the most milk per head, although demand for sheep’s and goats’ milk is rising to cater for people who find them easier to digest.

But what particularly arouses Kurlansky’s curiosity, over and above the eclectic miscellany of historical data he has collected, is that ‘milk is the most argued-over food in human history’. People have debated the importance of breastfeeding, the healthiness of milk, the best sources of milk, farming practices, animal welfare, the use of hormones in the US to boost milk product, the feeding of genetically modified crops on dairy farms, raw, as opposed to pasteurised milk, and more. The increasingly vociferous vegan lobby, which insists that ‘dairy is scary’, is just one contemporary manifestation of this perpetual discussion.

What is clever about his latest, highly readable volume, stuffed with colourful historical facts from all corners of the globe and epochs, is the playful way Kurlansky weaves in and out of these controversies, using a broad geographical and historical canvas to probe them. He opens his book by correcting ‘one great misconception’: that people who cannot drink milk have something wrong with them. ‘In truth, the aberrant condition is being able to drink milk.’ Lactose (milk sugar) intolerance is the natural condition of all mammals, he argues. In nature, the babies of most mammals nurse only until they are ready for solid food, then a gene steps in to shut down production of lactase, the enzyme that makes it possible to digest lactose properly. But he also throws in the apparent contradiction of all the populations — European, Middle Eastern, North African, Indians — who lack that gene and so have continued to drink milk into adulthood, without, one might note, any obvious difficulties.

Much later he returns to this subject and confounds the widespread belief that Asian populations tend to be lactose intolerant. Mongols famously drank mare’s milk and travelled carrying their dried cheese curds, formed into little logs that were chewy and slightly sweet, as sustenance. The Indian sub-continent, though universally credited as having the most evolved vegetarian cuisine in the world, is far from vegan. There is no cuisine that uses more dairy products than that of India, says Kurlansky, not even ‘the dairy-obsessed Dutch, Swiss and Scandinavians’.

Surprisingly, Japan has a milk tradition. In the 19th century, the government greatly encouraged milk drinking, believing that it would create larger, stronger Western-style bodies. In 1876, the Japanese government established a large dairy on the northern island of Hokkaido. To this day, Hokkaido milk is famous in Japan as a high-quality product.

Among the gastronomic offerings of the Tang dynasty (618–907) was a milky frozen dish, not exactly ice cream but made from fermented buffaloes’ milk, seasoned with camphor, and with flour added to give it solidity. One extravagant Tang luxury for the wealthy was koumiss, a confection made by skimming the fat off a fermented milk drink known as su. Kurlansky includes a blissfully succinct recipe for the Cantonese speciality, jiang zhuang nai, which translates as ‘ginger bumping milk’. ‘Crush ginger, or grate it, heat milk, pour over the ginger, and add a little sugar. Heat into a custard.’

Nowadays 40 per cent of Chinese drink milk, and China has become the world’s third largest milk producer, although a growing number of contemporary Chinese, anxious as a result of food contamination scandals, do not trust milk from their own country and are prepared to pay a premium for imported UHT milk and organic milk, even though it costs twice as much, because it gives them more peace of mind. Yoghurt parlours are trendy; yoghurt is regarded as new and hip. According to Kurlansky, affluent urban Chinese have a passion for cappuccinos and lattes and show little interest in espresso; it’s coffee with milk that everyone wants.

He recounts how Li Cheng, a doctor at Beijing University, started seeing patients in the 1980s with signs of lactose intolerance; all had adopted the new fashion for drinking milk. He and other doctors taught them to start by drinking only a little milk at a time and working their way up to more. Soon they were drinking it with impunity. Cheng and colleagues posited that their patients’ initial problem with milk was caused by not drinking it. If it was slowly reintroduced into their diets, their ability to tolerate it was restored.

Some Western gastroenterologists find this hypothesis implausible; they say that once the production of lactase is shut down genetically, it will never return. But cultural geneticists, who study how societal changes drive the evolution of genes, offer an alternative explanation: once humans had started raising livestock, the genetic shut-off of lactase started to disappear, so that humans could take advantage of the milk their animals produced.

As Kurlansky observes, after 10,000 years, a fundamental question about milk has still not been answered. That is, if a dairy did everything right, and its milk was perfect, would it be good for you? Is not the 60 per cent of the world that is lactose intolerant made the way nature intended humans to be? But then Kurlansky points out that to take medicine, wear clothes, farm or read is arguably unnatural, yet we do it. And enlisting scientific data to argue either for or against dairy consumption seems somewhat futile when, as he remarks, there are as many studies refuting any given set of findings as supporting them. ‘History has shown that as civilisation develops, it creates more, not fewer, arguments about milk.’ After reading Kurlansky’s rich, fascinating and comprehensive history, only a fool would beg to differ.