Flint and Mirror, John Crowley’s engrossing and elegant latest book, is set in a sixteenth century where angels and demons watch over human quarrels and sometimes even intervene. History and magic entwine, and yet are opposed. There is the ongoing conflict between Catholicism and Protestantism, as the Catholic Spaniards eye up invading England. The novel is also about the beginnings of modernity. As the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England comes to an end, we progress gradually toward exploration of the globe and the Enlightenment. Farewell rewards and fairies, indeed.

Elizabeth, serpentlike, broods in her English fastness, sending spies both physical and metaphysical throughout the land. Her personal magician, Dr. John Dee, communicates with heaven and is the possessor of obsidian mirrors that can be used to watch and control her subjects at a distance. This is the mirror of the title: a black shard tied onto the neck of young Hugh O’Neill, an Irish princeling, whom Elizabeth seeks out for aid in her conquest of the recalcitrant Emerald Isle. The hope of the Irish, however, is pinned on Hugh, a possible future High King who will rid them of colonial powers once and for all.

Brought in his childhood as a hostage to England, Hugh is adored by the court. But he knows that he is only a tool. The obsidian mirror is delightfully sinister: every time he looks into it, he sees the white, aging face of the Queen, who delivers instructions or court gossip. Hugh is torn. He loves his monarch, but he loves his country more. Also in his possession is a flint, given to him by one of the Sidhe, the supernatural beings who live under the ground. Their message is never explicitly delivered, but he knows they want him to save Ireland from the depredations of the English.

Crowley is a superb, accomplished writer, his prose bearing the texture of the past. One never feels, as with so much historical fiction, that this is a twenty-first-century writer imparting his own anachronistic hangups, philosophies and systems. Instead, here is someone trying to understand and present an actual sixteenth-century mind, where God is the highest power and the world around is populated with beings of all ranks, down to the humblest leprechaun. Crowley poetically imbues the novel with the ancestral mythology of Hugh’s upbringing. There are storm-raising wizards, shadowy figures of the pre-Christian Gaelic deities and princes who turn into geese. And yet all this does not feel like a fantasy novel, so grounded is it in the actualities of the premodern British world. When, during a sea battle, a cannonball appears with an angel riding on it, it seems absolutely right that it should do so.

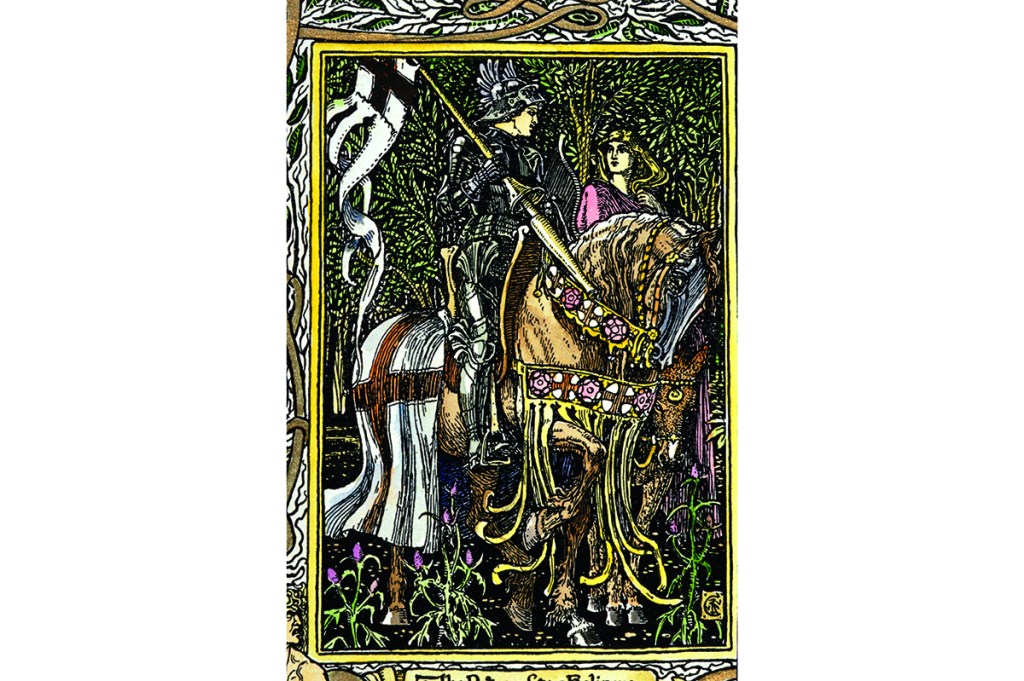

Wars and battles are beautifully conceived. This is a vicious, violent era, a time when swords are sharp and heads are placed on pikes. There are fluttering pennants, shining armor, towers and magic. Hugh, the “double-souled man,” is a fascinating hero: thoughtful and brave yet very much aware of realpolitik. He must toe the line, keeping peace within his lands, dealing not only with rivals in his own family but also with the colonials as well.

In one subplot a woman meets a selkie (a seal-human creature) and bears his child; meanwhile, her husband is told to kill his father, fails, and goes into exile. This story’s themes reflect wider ones: whom should the wife love? The interloper or the husband? Her son becomes a creature of two worlds, the sea and the land.

Those interested in the historical sixteenth century will enjoy the novel’s cameos. We meet my hero, the young Philip Sidney, whose father, Henry, figures in the book as the Lord Deputy of Ireland and a bold, valiant knight; we see Edmund Spenser, the poet, harried from his house in Ireland, returning to England with an unfinished Faerie Queene; there’s even a mention of Shakespeare. We also see, in a well-drawn scene, the rebellious Earl of Essex, bewitched by water nymphs who appear just out of his vision.

This is a finely worked tapestry of a book, glimmering with golds, greens, precious stones and metals. It is also a novel about twilight spaces, where things blend into each other; about the movement of intellectual thought from magic to rationality and the consequences of that movement. Crowley asks, what is man’s own impulse? Are we anything more than creatures of fate? He leaves it to you to come up with the answer.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.