In March 2021, during his last major interview, Jean-Luc Godard reiterated a previous point about the coronavirus being a form of communication. “At first, I thought that production was the main aspect of cinema, and I realized distribution was more important, today more than before. Distribution has choked production by pretending to be at the service of the audience…The virus in its own way, distributes. Today, it would be interesting to know how the virus produces, but we only care about what it distributes.” At ninety years old, Godard was free-associating about something we’d been living with for a year, which he somehow made new and interesting

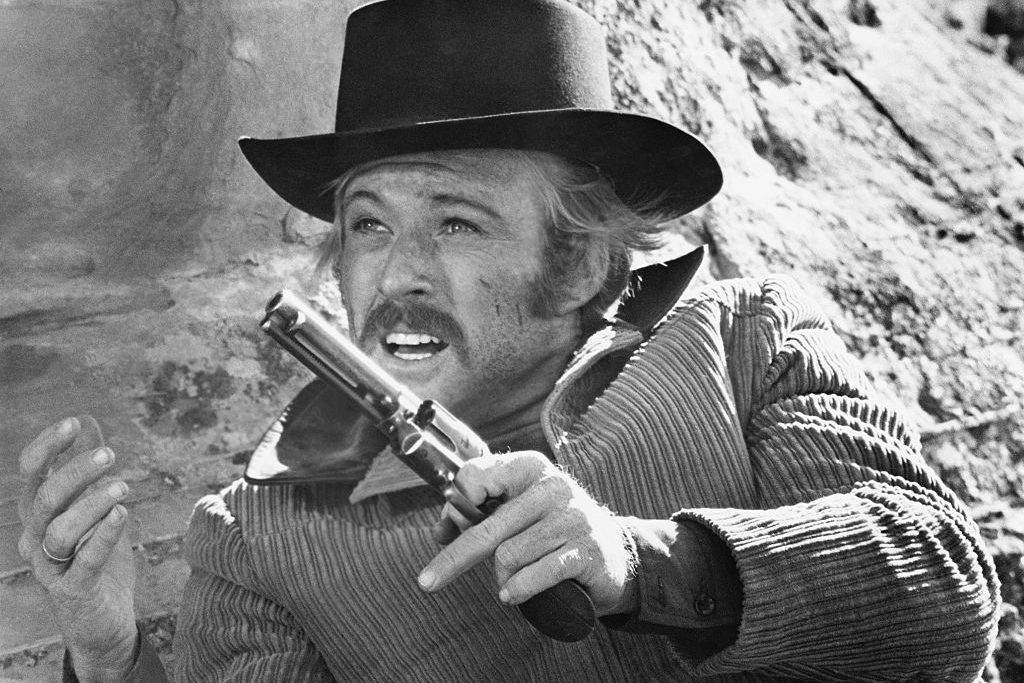

Godard’s aperçu is as succinct and incisive as any of his famous aphorisms about girls, guns and truth at twenty-four frames per second. Seen another way, it is a facile comparison between the pandemic and the particulars of the film industry. Godard was always two (or three) things at once, as much a serious intellectual as a public prankster, a man whose movies never take themselves too seriously. Still, for every unimpeachable masterpiece like Vivre sa vie or Pierrot le Fou, there are twice as many video shorts that have a reputation as “difficult” when they’re just as spirited as the “classics” with Anna Karina.

In his half-decade of radical chic Maoism during the late 1960s and early 1970s, Godard, along with Jean-Pierre Gorin (and, later, his longtime partner Anne-Marie Miéville), made films that were practically unwatchable, but carried the innocent curiosity of a child, no matter how heady (or stupid) the politics became. In Vladimir and Rosa, the Chicago Eight trial is recreated with students and a ridiculous-looking judge, with scenes of Gorin and Godard playing tennis with the “defendants.” Thankfully, they both got Red Book juvenilia and aesthetic allergies out of their systems in time to produce 1972’s Tout va bien, a collaboration with Jane Fonda that remains one of the best unions the cinema has ever produced. Every set piece is as formally precise and politically astute as it is hilarious, especially the long back-and-forth tracking shot of a grocery store riot that ends the film. It is obvious why certain slices of Godard’s body of work get overlooked, but even within his rightly famed fifteen-film run from 1960 to 1967, there are neglected gems. Consider A Married Woman, his bold structuralist response to friend François Truffaut’s dull and creaky infidelity thriller The Soft Skin, or Alphaville, a predecessor to The Matrix, where Eddie Constantine must infiltrate a future city controlled by a fascistic supercomputer. Even A Woman is a Woman, a scrappy but vivacious deconstructed widescreen musical, gets passed over in favor of the same five or so films that have overtaken his canon.

Cinema was a playground for Godard. He left us dozens of exemplars of the medium, which he continued to push forward for the rest of his long life, almost single-handedly. Godard’s career made it through twelve American presidential administrations. For him there was no separation between filmmaking and criticism, as he told Film Comment in 1996:

I don’t make a distinction between directing and criticism. When I began to look at pictures, that was already part of movie-making…There is no difference. I am part of filmmaking and I must continue to look at what is going on…

After the exuberance of his 1960s run, and his gleefully manic and insightful film reviews for Cahiers du Cinéma in the 1950s, Godard went through a crisis of faith with cinema and, by the 1980s, became convinced that the medium had abandoned its sacred duty “to catch reality.” His opposition to the films of Claude Lanzmann and Steven Spielberg is well-documented, and while his anti-Zionism never veered into antisemitism, the juxtaposition of Henry Kissinger, Emma Goldman and a woman’s rear end in Ici et Ailleurs remains provocative.

In that film, and so many others, the central question is the image. For example, Miéville points out to her partner that he could’ve picked any Palestinian to appear on camera and read a statement, but he picked a charismatic and attractive young woman. His magnum opus Histoire(s) du Cinéma revolves around the atrocities of the twentieth century and their codependent relationship with cinema, along with Godard’s history in the only form that gave him any sense of self.

From that final interview in March 2021: “The way I wish a movie should be is a utopia, but to make a movie, to make it, is not utopia.” His final (and best) film, 2018’s The Image Book, ends with the following voiceover by Godard: “And even if nothing would be as we had hoped, it would change nothing of our hopes, they remain a necessary utopia.” Godard’s work remains a vibrant pageant of cinematic possibilities.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2022 World edition.