The world is moving into a more dangerous age. According to the Peace Research Institute Oslo, last year set a grim record: the highest number of state-based armed conflicts in more than seven decades. At the same time, we are seeing a fundamental realignment of global geopolitics – made clear from the recent meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the “Victory Day” parade held in Beijing shortly afterwards. There, the leaders of what many in the West regard as an emerging new world order stood shoulder to shoulder as Chinese military hardware was put on display to mark 80 years since the end of World War Two.

That anniversary also meant the commemoration last month of the only two occasions where atomic bombs have been used. Their detonation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was so horrific that they played an important role in the fragile balance that characterized the Cold War. Fear of nuclear war scarred generations, with a well-grounded anxiety that the use of a single warhead might result in a retaliation so severe that military strategists came to talk of the doctrine of “mutually assured destruction.”

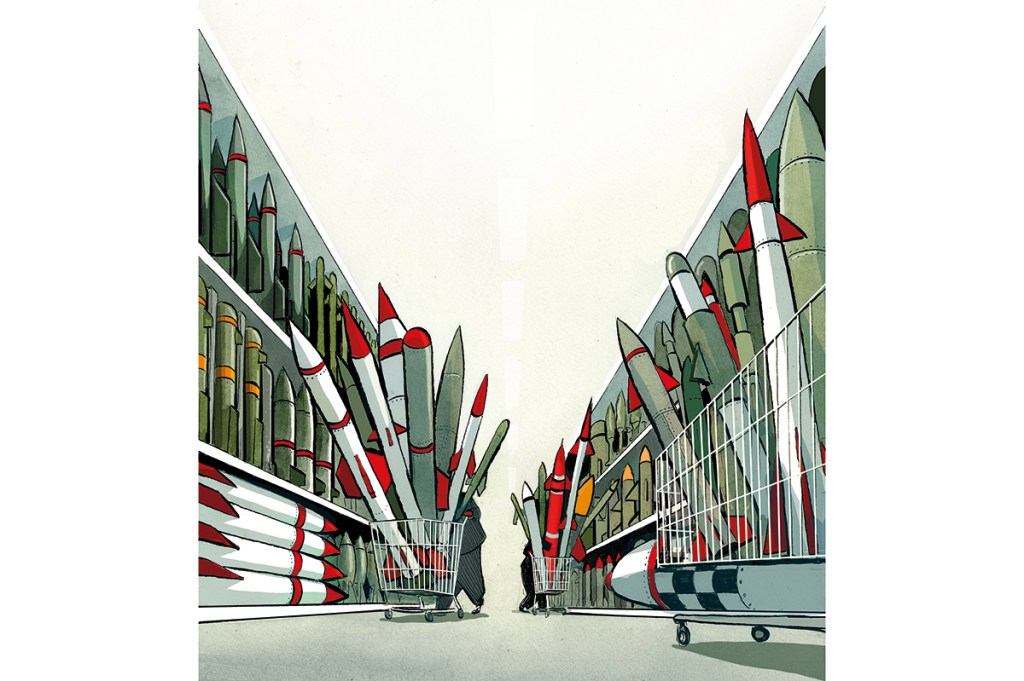

What was unimaginable a decade ago is now seriously discussed in newspapers and research institutes

Now, thoughts are turning in many quarters to whether it’s time for a new chapter in the bleak history of nuclear weapons proliferation. Lessons from Ukraine and the Middle East have shown the use of force can pay handsome dividends. The sense that things have changed has become mainstream even in the US, which has played the role of guarantor of the rules-based system since 1945. As Marco Rubio put it earlier this year: “The postwar global order is not just obsolete, it is now a weapon being used against us.”

Not surprisingly, then, in some parts of the world the US is thought to be using coercion to reshape the world in its favor through the application of tariffs as economic punishments. But the threat of military force, too, has been a signature of Donald Trump’s year in office. Many take the President’s comments about the possible annexation of the Panama Canal to Canada with a grain of salt; but many do not. In March Vice-President Vance stated that “the President said we have to have Greenland… We cannot just ignore this place. We cannot just ignore the President’s desires.” The new world order, in other words, depends on the whims of a single individual, whose wishes apparently cannot be ignored.

All of this – made worse by worries about economic challenges and large-scale migration – has spurred a set of discussions in many countries about how to prepare for an age of fracture, competition and new rivalries. Some of these discussions have been fueled by technological leaps, including automation, drones, AI and robotics, which will radically lower the cost of war, making military confrontation more thinkable.

In a world of multiplied pressures and fragmented power, it is chilling – but perhaps not unexpected – to find voices calling for the development of nuclear-weapons programs to provide a new line of defense against possible state-on-state violence.

Such conversations have been fundamental to Iran for several decades – one reason for the dramatic events of the “Twelve-Day War” in June, when Israeli jets targeted nuclear facilities, as well as some of the most senior Iranian scientists working on enrichment and delivery systems.

It is discussions in other countries, however, that have been particularly striking. Take Turkey. The country has long been a key member of NATO, with B61 nuclear bombs held at the airbase at Incirlik a vital part of western defense capabilities in the time of the Soviet Union, as well as today. For decades, Ankara kept its own ambitions firmly in the realm of a civilian nuclear program. This summer, though, more commentators have been arguing that not only does Turkey possess both the scientific base and natural resources to pursue enrichment, but that only an indigenously designed and manufactured bomb would truly constitute “mutlak caydirıcilik” (absolute deterrence).

For one thing, nuclear self-sufficiency would be an alternative to having to rely on NATO. Much has also been made about the fact that Israel – Turkey’s primary rival in Syria and beyond – has an undeclared arsenal and acts unilaterally as a result. The recent strike on the Qatari capital of Doha, targeting the remains of Hamas’s leadership, was a stark display of Israel’s capabilities, which emboldened it to carry out what the Emir of Qatar called a “reckless criminal act” and “a flagrant violation of international law.” To many in the region, the support given to Israel by the US is significant, but its nuclear capabilities provide it with its ultimate layer of protection.

Even Pedro Sánchez, the Spanish Prime Minister, noted that his country’s ability to restrain Israel is compromised by the fact that Spain does not have aircraft carriers, “large oil reserves,” or nuclear bombs. By this he meant that Spain has a limited capacity to influence global affairs. “That doesn’t mean we won’t stop trying,” he added.

The point has been made many times in the Turkish press over recent weeks that Iran was vulnerable to Israeli attacks because of the “cifte standart” (double standard) by which Israel is allowed nuclear arms while Iran is punished for enrichment. As one commentator put it, when small or medium-sized states are forced to ask what genuinely prevents attacks, the answer is increasingly obvious: nuclear deterrence.

Public opinion has started to move in the direction of support for Turkey acquiring nuclear weapons – just as it has elsewhere. In Poland, on another part of NATO’s eastern frontier, calls for the country to host nuclear weapons have grown, while in some quarters the question has begun to be asked whether the country needs its own deterrent. One catalyst for this has been the war in Ukraine; another was Moscow’s 2023 announcement that it would station nuclear warheads in Belarus.

The recent incursion of Russian drones into Polish airspace, in what Prime Minister Donald Tusk made clear was not a mistake, will only increase demands to boost Polish defense readiness – not least because some senior figures in Russia have proposed using a nuclear strike to deter western support for Ukraine. The risks, wrote the Russian political scientist Sergei Karaganov last year, are low: if Russia used a device against Poznań, the US would not dare to retaliate. Doing so would risk sacrificing Boston for a Polish city and only a “madman,” Karaganov suggested, would consider doing that.

And then there’s Trump’s unpredictability and perceived hostility toward Europe. This month, Pentagon officials informed European diplomats that the US was no longer willing to fund programs to train and equip militaries in Eastern Europe, creating a hole in defense expenditure worth hundreds of millions of dollars. That is a problem, but just as important is the messaging that Europeans are on their own.

This has not been lost on the Poles. Former president Andrzej Duda has declared that Warsaw is indeed ready to join NATO’s nuclear-sharing program and to host US weapons – though some fear that Washington’s retreat might make that a pipe dream.

According to leaks earlier this month from the forthcoming National Defense Strategy, the new consensus in the Trump administration is to disentangle the US from foreign commitments and to prioritize places closer to home – such as Central America and the Caribbean – rather than focus on China, Russia, or other faraway places. Inevitably, that leaves Europeans feeling exposed, especially those on its eastern flank. It’s also a reason why even Germany, a country that has prided itself on a moral as well as military abstinence, has seen a growing debate about how best to counter the threat posed by Putin’s Russia.

Even before Trump’s re-election last year, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung published essays debating whether Germany should consider an independent deterrent or support a Franco-British umbrella. Other newspapers have since followed suit, asking if Europe must not only learn to “love the bomb,” but must develop one itself in the face of current US foreign policy. Leading think tanks have started to turn out papers urging deeper nuclear dialogue inside Europe – including around developing weapons and delivery systems. What was unimaginable a decade ago is now seriously discussed in mainstream newspapers and research institutes.

Even in Japan, the only country to have atomic bombs used against it, public sentiment has been changing

Similar questions are also being asked across Asia, with debates driven by proximity to threats – perceived or otherwise. South Korea lives in a nuclear neighborhood that has become increasingly precarious. North Korea is thought to possess as many as 50 nuclear warheads, and enough fissile material to make dozens more. Its deepening partnership with Russia has seen its men and weapons reinforce the front lines in the Ukraine war, while advanced technologies, including missile systems, have flowed in the other direction. North Korea is not just a problem for Washington; it’s a permanent feature of Seoul’s security environment.

Against this backdrop, South Korean public opinion has swung heavily toward nuclear options. Polling by the Asan Institute – a Seoul-based think tank – shows more than three-quarters of citizens favoring either an independent bomb or the redeployment of US tactical weapons, which were removed at the end of the Cold War as part of the Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

Even in Japan, the only country in history to have atomic bombs used against its people, public sentiment has been changing. Tokyo has been careful to develop advanced fuel-cycle technology and large plutonium stocks. So far, calls for a domestic nuclear weapons program have been muted – at least in public. Behind closed doors, however, some senior figures admit that exposure to risk is rising in a rapidly changing world. Having allies in North America and Europe is all well and good, but with competition in the South China Sea more likely to increase than to diminish, anticipating problems has become increasingly important – one reason why Japan’s defense budget has risen for 13 years in a row, with spending up almost 10 per cent this year alone.

Another, closely connected, reason is the buildup of Chinese hardware. In 2024, for example, a single shipbuilder in China produced more tonnage than the US has done since 1945. The rate of expansion of China’s nuclear arsenal has been breathtaking as well, with around 100 warheads estimated to have been added since 2023. In ten years, some reckon that China’s arsenal could almost triple – putting it at parity with the US and Russia in terms of the number of its devices ready for use at short notice.

As in Europe, it has dawned on politicians in Asia that decades of over-dependence on US security – and US taxpayers – are coming to an end, leaving a set of existential questions on how to invest in defense and how to do so quickly. Japan remains committed to non-nuclear principles, but talk of nuclear options is no longer unthinkable. Taken together, these cases underscore the prospect of the erosion of the old nuclear order and prompt fears of a new era of proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. Iran has been on the edge of being nuclear ready and is thought to be more or less nuclear capable. In Saudi Arabia, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has been explicit, saying that while “we are concerned [about] any country getting a nuclear weapon,” if Iran did develop a weapon “we will have to get one.”

The world is heading into a decade of uncertainty. If more states do cross the nuclear threshold, they will have to develop not only the weapons themselves, but also the doctrines to guide their possible use. History shows that the process of drafting those doctrines can itself be destabilizing, as rivals attempt to divine intentions and try to work out how to respond, in theory and in practice. It remains uncertain, too, how the US or China, both of which have consistently voiced opposition to further proliferation, would react if partners or adversaries seek to join the nuclear club. What is certain is that every new entrant adds complexity to an already fragile system.

These risks are not abstract. Confrontation between nuclear-armed states carries the prospect of catastrophe on a global scale. The world has come close before, whether during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, or this year in South Asia, where tensions between India and Pakistan were on the brink of escalation.

Each of these near-misses underlines the same truth: nuclear weapons are not just the last line of defense but also the last line of existence. As more states contemplate acquiring them, the space for miscalculation grows ever wider – and the margin for survival ever thinner.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 29, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply