We’re all worried about older people right now. But I’m worried about the young too. I fear they lack the social nous and moral muscle to deal with a crisis as profound as the COVID-19 pandemic. I fear that the cult of fragility is so widespread among the youth that some will struggle to rise to the occasion of facing down this wolf at the door of our society.

Our first priority must be the elderly, of course. We know COVID-19 is more dangerous for them than it is for other age groups. (Though I wish the media would stop giving the impression that every old person who catches it dies. That isn’t the case. To spread fear among the old is its own kind of disease, causing moral and mental harm to people who often feel isolated enough as it is.)

But in order to protect the elderly through these dark days — dark months, in fact — we need strong social networks. We need real social solidarity. And as John Stuart Mill understood so well, a strong society springs from strong-willed individuals. Society needs ‘strong natures’, he said, because the ‘same strong susceptibilities which make the personal impulses vivid and powerful are also the source from whence are generated the most passionate love of virtue’.

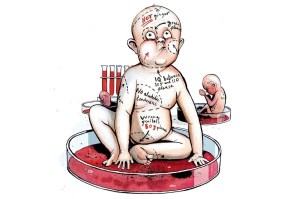

This is one of the most serious problems we face in the 21st century: a shortage of ‘strong natures’. Today it’s cooler to be a victim than to be proudly morally autonomous. We are encouraged to advertise our wounds rather than to celebrate our free-willed achievements. ‘Fragile natures’ are the order of the day, especially among the young, who interpret every slight as a mortal blow to their self-esteem and every disagreeable idea as an act of structural oppression.

We have taught this new generation to fear the tussles and difficulties of life itself. The education system promotes self-esteem, which is pretty self-explanatory: it encourages kids to esteem the self over all else.

Colleges are overrun by ‘safe spaces’ in which the young take refuge from the hardships of critical thinking and differences of opinion. Trigger warnings are attached to books lest the content within should startle the youthful reader and — crime of crimes — cause a dent in his sacred self-esteem.

Parenting has changed, too. Children go out less. They get into fewer scraps. The number of youngsters with Saturday jobs has plummeted. Survey after survey suggests the millennial generation is smoking less, drinking less and screwing less than previously generations — a testament to their resistance to adulthood, to their desire to stay in the perma-kindergarten of the safe space for as long as possible.

The end result of all this is a generation lacking in resilience. To make matters worse, the most popular political trends among millennials — in particular, the politics of identity and the fashionable generational disdain for older people — mix together with the cult of fragility to create a generation that often appears adrift from society.

The politics of identity, with its obsessive focus on one’s own gender identity and sexuality and racial history and so on, elevates navel-gazing into an art-form. And the often quite nasty politics of generationalism, in which boomers (by which they really just mean old people) are viewed with naked disdain, cuts the young off from their elders.

People refer to COVID-19 as a perfect storm. But the trends and ideas shaping today’s young add up to a perfect storm, too. Performative weakness, identitarian self-obsession, ageist aloofness from older people and their wisdom: this is the storm of influences that have stripped the young of the ‘strong nature’ that is so central to a strong and healthy society.

This isn’t their fault, of course. This is a story of social neglect. As a society we have neglected one of the key tasks of the intergenerational relationship: to confer knowledge and strength into the young. Instead we have flattered their self-pities and inculcated in them a fashion for weakness.

And this is my concern: at a time when society really needs to pull together, when we urgently require cross-generational bravery and solidarity, will the young be up to the task? Will they partake in the kind of self-negation and risk-taking that are essential to the ‘passionate love of virtue’ that Mill saw as central to the good society?

Of course, all is not lost. For a start, this culture is not omnipotent among youths. Many, many young people bristle against the cults of identity and fragility as much as older people do. Moreover, there’s nothing like a genuine social crisis to draw out people’s latent desire for social connection, for being a genuine player in something bigger than themselves.

Will COVID-19 do this? Will this biological threat encourage millennials to ditch their eccentric obsessions with gender expression and woke correctness and open their eyes to the need to step out of yourself and into the world? Let’s hope so.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.