It wasn’t a coincidence that the US government chose Ellis Island as an immigration station. The crucial word is ‘island’.

Had the RMS Titanic missed that fateful iceberg in 1912, she would eventually have taken up station at a quarantine area at the entrance to the Lower Bay of New York Harbor, to await medical inspectors who would board the ship from a cutter.

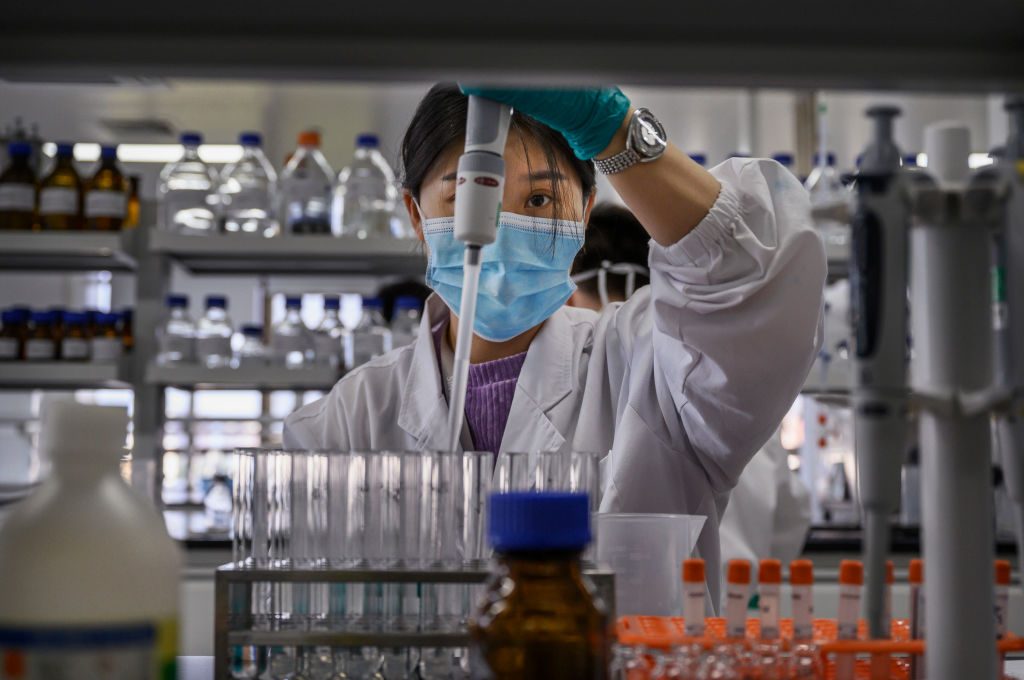

The quarantine exam would have been performed aboard, but only for first- or second-class passengers (US citizens were exempt). These would have been inspected for cholera, plague, smallpox, typhoid fever, yellow fever, scarlet fever, measles and diphtheria. A few might have been marked to be sent to Ellis Island for further examination.

Much of the world’s tourist and travel industry is dependent on the continued efficacy of vaccines and antibiotics

Only after the visiting medical inspectors had returned to shore would the Titanic have sailed into the main harbor, docking at the White Star Line’s Pier 59 on Manhattan, There only the pre-vetted cabin-class passengers would have disembarked. All steerage passengers would have been transferred to barges for the trip to Ellis Island and at least five hours of further processing — and possible rejection or quarantine.

As for those famous locked gates on the Titanic which separated third-class areas of the ship from everyone else, and which subsequently provided rich material to filmmakers wishing to pass comment on British class divides? These had been installed to comply with US immigration law, again to control the spread of disease on board.

What if this becomes normal again? It is chastening to contemplate the extent to which we have built the whole edifice of the modern world on the assumption that no technological gains can ever be lost. Electricity is the most widely cited example of this (with parts of the world perhaps permanently a few gigawatt hours away from chaos and civil unrest). The internet is another. But we could equally claim that much of the world’s tourist and travel industry is entirely dependent on the continued efficacy of vaccines and antibiotics.

As someone old enough to remember the opening sequence of Terry Nation’s 1975 BBC post-pandemic drama Survivors, my greatest surprise at the coronavirus outbreak is that it has not happened before. The change in travel habits that has happened in a generation is staggering. In 1984, when I was 20 and at university, I had traveled abroad only to France and Spain, and had flown twice. When I quizzed my American fellow students about the United States, it was on the assumption that I might never go there in my lifetime. Hardly anyone I knew had taken a long-haul flight, except a few elderly rich people, and that was for a three-week visit. I now have no clue how many times I have crossed the Atlantic.

The widening of travel is wonderful, of course. But I can’t help wondering if we would have appreciated it all the more had it become available to us more slowly. This is the curse of free-market capitalism in many ways. You get to choose everything about your life except the pace at which it changes.

Looked at optimistically, the coming months are an extraordinary opportunity for us to rediscover time-intensive, slow pleasures we would never have found time for otherwise. Read Proust. Master cryptic crosswords. Form a string quartet. Learn to speak Arapaho.

Perhaps when this is over, we won’t look at time in quite the same way again. Or travel. Or communication. We might also pay a little more attention to matters closer to home. For now, the most useful thing you can do is keep an eye on each other.

Rory Sutherland is vice-chairman of Ogilvy UK. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.