Early last week I bought myself a teapot. I have several, but I could not resist this with its turquoise Mediterranean charm. Alongside I purchased tea glasses — not mugs or cups, but glasses. The Turkish way. It comes with a milk jug. The English way. Excited to use them for the first time early in the morning, I went to the kitchen where I found my seventy-four-year-old mother, who was visiting us from Ankara. Her eyes were red and swollen from crying. She spoke in a voice so low that I struggled to hear at first. “There has been an earthquake.” The glass in my hand felt small and fragile. We both knew what the next question was: “Did anyone die?” I asked. She started crying again.

As I write these words the death toll from the twin earthquakes in southern Turkey and northern Syria is close to 40,000, though the full scale of devastation is still unknown and the real number is estimated to be at least twice as high. What made the disaster even more catastrophic was not nature itself, but a human-built system of inequality, corruption, mismanagement and nepotism. The sad truth is an alarming number of buildings in my motherland are not up to code. The AKP government under President Erdoğan kept issuing “construction amnesties” which allowed dodgy contractors to skip safety regulations. The government has also collected “earthquake tax” from its citizens for many years, but no one knows where the money was spent.

There is a correlation between the lack of democracy in a country and the extent of the destruction and the inadequacy of rescue efforts in the wake of a natural disaster. Erdoğan says no government could have been prepared for an earthquake of this magnitude, but that is not true. The death toll would not have been this terrible if the rescue efforts last week had been properly coordinated and if building regulations had been implemented. On social media, trolls attack critics, as they always do. “Don’t you care about the image of your country?” says one of them. I wish we had cared about truth as much as about “image.” Turkey’s ruling politicians will do everything in their power to blame individual contractors, many of whom are guilty, but the authorities cannot gloss over the fact that all these years they have paid no heed to scientists’ warnings. They will also probably try to postpone May’s presidential election. No matter how long they put it off, though, people can never forget this pain.

In the days following the earthquakes, I had an interview with NPR’s Scott Simon. For the first time in my life I choked back tears in an interview, struggling to speak. Millions of people, both in Turkey and across the diaspora, oscillate between sorrow and rage. I exchanged emails and calls with other artists and writers, trying to organize a collective reading to raise money, trying to find ways to help.

There were incredibly touching moments of humanity in the wake of the disaster. Rescue teams flying from all over the world — from Spain to Greece to Mexico to the UK, and even Ukraine — saved many lives. But it was also worrying to see how some far-right Turkish groups started attacking Syrian refugees. At the same time here in the UK, my adopted country, far-right protesters gathered around a hotel in Merseyside housing asylum seekers. They clashed with the police and set alight a police van. I remember a memorial in Liverpool dedicated to dead refugees, designed by the Istanbul-based artist Banu Cennetoglu, which was sprayed with the slogan: “Invaders not Refugees.” There has been a rise in jingoistic rhetoric, which some politicians find it convenient to stoke, looking for the next vulnerable group to blame for the sorrows of this world.

Novelists do not have interesting lives, as a rule. Even though too many creative writing courses continue to drill into students the old dictum “write what you know,” the truth is that “write what you feel” is far better advice. Our imagination is wilder and bolder than our real-life experiences, which can be rather dull, to be honest. When my son was little he once asked me, without any judgment: “Mum, is it very depressing to be a writer?” I did not think so, but nor could I claim it to be a very joyful existence. Sitting in a room on your own every day; reading, taking notes, without quite knowing if it will lead anywhere. Small things can therefore make a huge difference when you are in the middle of a story — personal ornaments, colorful notebooks… Perhaps this is why I’ve decided to take up mudlarking. Walking on the river at low tide, looking for discarded items speaks to me. Maybe I will find a broken teapot, cherished by some writer from days gone.

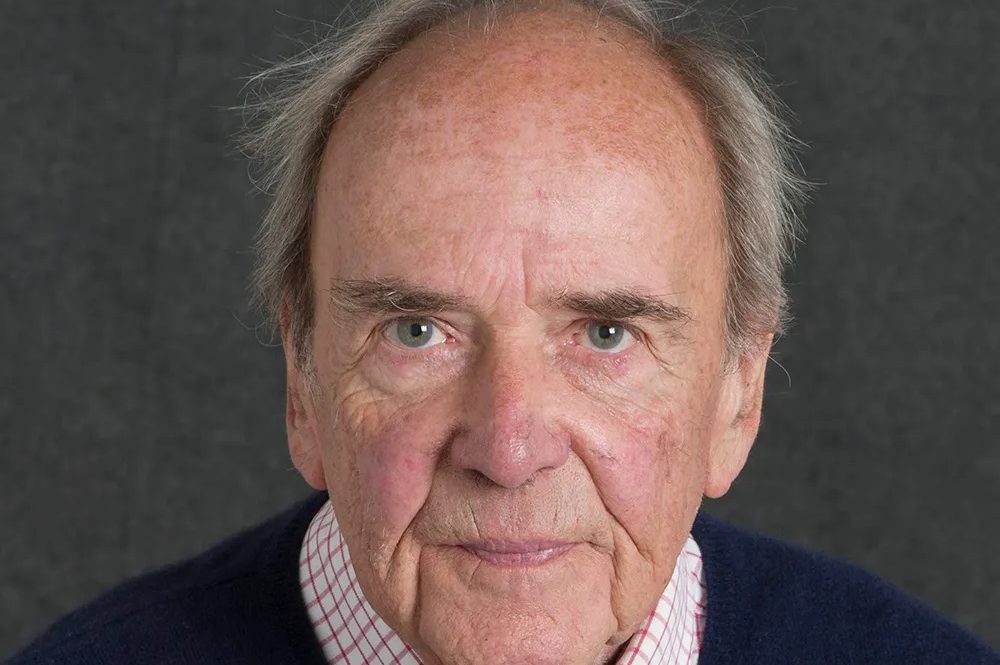

Elif Shafak’s The Island of Missing Trees is out now. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.