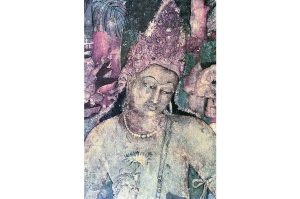

As Perseus was flying along the coast on his winged horse Pegasus, he spotted Andromeda tied to a rock as a sacrifice to Poseidon’s sea monster Cetus. It was love at first sight. Perseus slew Cetus and married Andromeda. Thus began the damsel-in-distress archetype that has been a mainstay of western culture ever since. Riffs on the archetype have been used by Chaucer, Shakespeare, Dickens and Wagner. Perhaps it was these examples that inspired the global liberal establishment (the BBC, Hollywood and the Nobel Peace Prize committee among others) to create, in the 1990s, the mythical version of Aung San Suu Kyi, Burma’s ‘imprisoned princess’, the saintly spiritual heir to Mahatma Gandhi, as TIME magazine described her.

Aung San Suu Kyi, or The Lady as she has become known, was a perfect clothes horse for the western media’s utopian fantasies. Hollywood was also hooked. Those most self-regarding of moral arbiters, Angelina Jolie and Emma Thompson, beat a path to her door. So too did former Bond girl, the glamorous Michelle Yeoh, who went on to take the lead role in The Lady, Luc Besson’s 2011 syrupy hagiographical biopic.

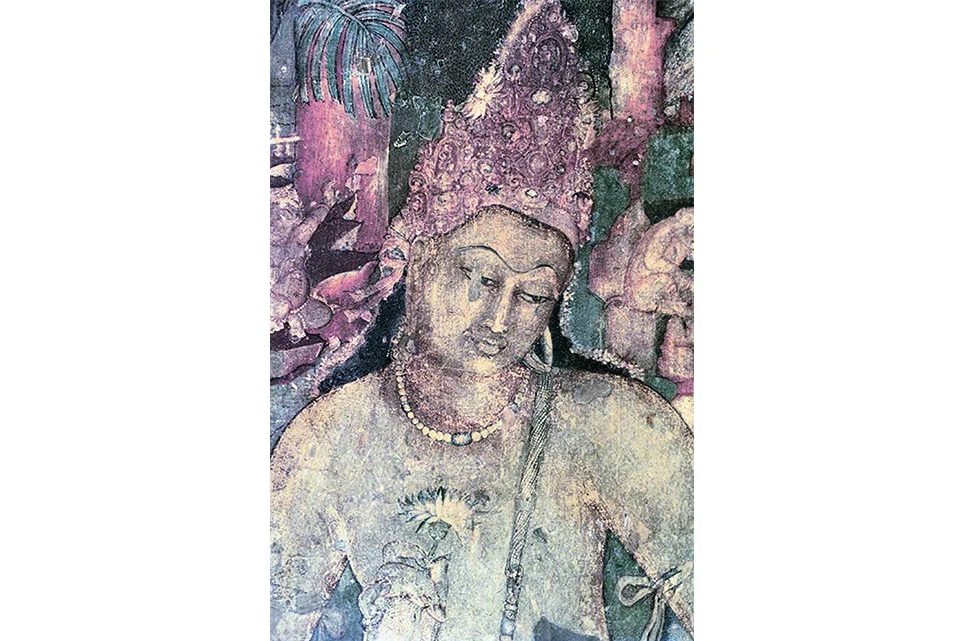

Now, however, these liberal western fantasies have evaporated. Last month, the European parliament decided to suspend The Lady from the ‘Sakharov prize community’ 20 years after she was handed the peace award — becoming the latest previously sycophantic institution to make such a humiliating U-turn.

The Lady’s myth began when she returned to Burma in 1988, leaving her husband and children behind in Oxford. She helped to found the National League for Democracy and drew huge crowds in rallies that presaged overwhelming electoral victory in 1990. When the military junta incarcerated The Lady she became an instant hero, winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. Her other awards include the International Simon Bolivar Prize, the Olof Palme Prize, the Freedom of Oxford, Ambassador of Conscience award for Amnesty International and the US Congressional Gold Medal. Over the next two decades the bemedaled Lady spent all but six years under house arrest in her dilapidated lakeside house.

After she was released in 2010, politicians clamored to be seen with her. British prime minister David Cameron broke parliamentary protocols to allow her to address parliament. Speaker John Bercow preened, ‘the courage of our guest is legendary’. In 2011 she was invited to present the Reith Lectures for BBC Radio 4. That December Hillary Clinton came calling. She shared hugs and kisses with Barack Obama at the White House.

But her reputation hit the buffers of political reality after she assumed power as State Counsellor (effectively prime minister) in 2016. Almost immediately The Lady’s rule became defined by the Rohingya refugee crisis. Within a year she went from hero to zero.

The problem of the Rohingyas in the Arakan began with Britain and its conquest of the region in the first Anglo-Burmese war of 1824-6. Tacked on to Britain’s Indian Empire, the opening up of borders brought Muslim (Rohingya) and Hindu migrants into an area that was home to both Burmans and the Arakanese. As Human Rights Watch explained, in 1982 new nationality laws ‘effectively denied to the Rohingya the possibility of acquiring a nationality’ even though some of their families had lived there for hundreds of years. Thereafter the Rohingya suffered military crackdowns in 1991-2, 2012, 2015 and 2016, ending in the genocidal drive in 2017 to remove 750,000 Rohingya from within its borders and into refugee camps inside Bangladesh. At least that is the simplistic anti-Myanmar slant of the western media and the NGO community.

The real but highly complex story eludes the ideological grip of most of these actors. In the aftermath of 9/11, the Rohingya became increasing infiltrated by jihadists trained in Pakistan. In the succeeding decade Myanmar’s military sought to crack down on these groups, notably the Harakah al-Yaqin (Faith Movement) before it changed its name to ARSA, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army; presenting itself as a liberation force rather than a jihadist terrorist organization made ARSA more respectable to liberal fellow travelers in the West. Largely eviscerated from the dominant western narrative is that ARSA terrorism precipitated a Buddhist and Hindu refugee crisis as they fled from jihadist atrocities in northern Arakan.

The events that led to the dramatic escalation of the Rohingya crisis were a series of co-ordinated ARSA attacks on police stations and military on August 15, 2017. It was no coincidence that these terrorist atrocities occurred the day after the publication of Kofi Annan’s Advisory Commission Report advocating a well-considered way forward to bring the Rohingya into Myanmar citizenship. ARSA’s jihadists had at a stroke deliberately sabotaged any hope of a negotiated settlement.

In the Tatmadaw’s (Myanmar army) ensuing clearing operations, villages were burned and there were rapes, tortures and other atrocities by vengeful Burman troops. However, much of the carnage that occurred was probably carried out by other participants, notably extremist Buddhist militias and the Arakan Army. In its quest for independence from Myanmar the AA looks back to the glories of the Arakanese kingdom (1489-1784). The AA, in alliance with the Kachin Independence Army, comprise some of the up to 40 disparate armed groups now fighting in the mountainous jungles of the Arakan.

Further complexity is added by India’s attempts to develop a cargo route from its impoverished north-eastern states of Tripura and Mizoram down the Kaladan River to an Indian-financed deep-water port at Arakan’s capital city of Sittwe. China, with its sights set on control of the Bay of Bengal, in its typically Machiavellian way, is thought to be financing terrorist groups to attack Indian civil engineers. In this confusing mêlée, the claims that the Myanmar government ordered a genocide are thinly substantiated. More plausibly, the Rohingya flight to Bangladesh was simply an escape from the terrorist-Tatmadaw conflict.

As for the future, by fanning the unproven genocide narrative, ARSA has helped increase funding from Wahabi elements in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere to finance terrorist training. Moreover, radical madrasas within refugee camps are indoctrinating Rohingya youth with jihadi ideology. These developments make the possibility of a Rohingya return to the Arakan unlikely in spite of sporadic negotiations with Myanmar’s government.

***

Get a print and digital subscription to The Spectator.

Try a month free, then just $7.99 a month

***

Although in security matters The Lady is constitutionally powerless, given Tatmadaw’s fiat in this area, there is little doubt that she supports their fight against ARSA terrorists as she demonstrated in her forthright testimony at the Rohingya genocide hearings at the International Court of Justice in The Hague in December. To do otherwise would have undermined Burman and Buddhist support for her NLD party, particularly in the run-up to next month’s general election. The Lady is both a Burman patriot and political realist far removed from the fantasy princess imagined by the western liberal establishment. The clue should have been in her ridiculous laudatory biography of her father, ‘Bogyoke’ Aung San, the first leader of an independent Burma. He was an avowed admirer of Hitler and Mussolini who led the Burmese forces that fought with Hirohito’s invading armies at the start of the Pacific war. His murder of a village headman and the depredations of his troops against Burma’s ethnic minorities were conveniently expunged from The Lady’s narrative.

Aung San Suu Kyi is her father’s daughter: aloof, fearless and autocratic. Notwithstanding her bravery in standing up to Myanmar’s vicious and corrupt military regime, she has cracked down on press freedom with greater determination than the military junta that preceded her. Sadly, albeit charismatic, she possesses none of the other qualifications that would make her a suitable leader of her country. She is famous for lacking managerial skills, or tact. After a bruising interview with the BBC’s Mishal Husain, The Lady peevishly complained: ‘No one told me I was going to be interviewed by a Muslim.’ It was the final nail in the coffin of her reputation with the liberal establishment.

In building up Aung San Suu Kyi as their nonpareil, the media set themselves up for a fall. Although The Lady was always quick to refute her saintliness, nevertheless, for her perceived betrayal, the media’s fury knows no bounds; for them the imprisoned princess has transformed into the wicked witch. While it is easy to laugh at the discomfort of the liberal establishment, it is less funny that we are hostage to the western media’s un-nuanced analysis of the Rohingya issue. Even more importantly the West’s narrative of the crisis is pushing Myanmar inexorably into the hands of China. Is this what our leaders want?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.