Second Amendment supporters will have cheered the news this week that the newly-Trumpified Supreme Court will hear its first gun rights case in over a decade. The case, a challenge to a New York City law forbidding gun owners from taking their weapons to shooting ranges beyond the city, is scheduled to be heard (and most likely upheld) in October.

Going on facts alone, this case isn’t hugely exciting (concerning, as it does, an idiosyncratic law in a city where most folks don’t own guns anyway). What’s more interesting is the potential wider implications – something which might see the Court forced to make up its mind on much bigger, and more salient, controversies around gun ownership.

The Supreme Court doesn’t take on gun cases very often. Since its landmark ruling in DC v. Heller (2008), it’s declined to hear cases on issues like compulsory waiting periods and assault weapon bans. This led to a stinging rebuttal from Clarence Thomas, in February last year, that the Court’s distaste for gun cases had made the Second Amendment a ‘constitutional orphan’. Ouch.

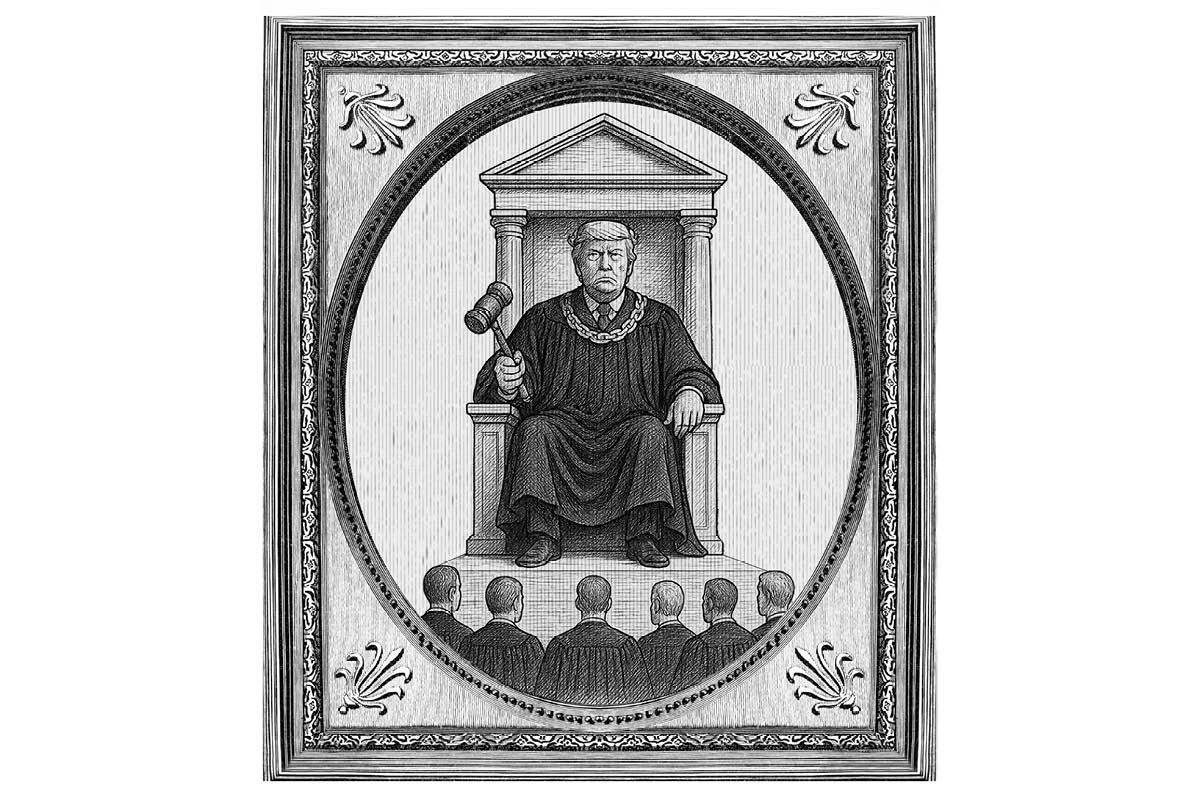

Following the appointments of Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh, many suspect that’s all gone out of the window – hence why all eyes will be on the NYC case in October. If the majority votes to take a muscular approach to the Second Amendment (so-called ‘strict scrutiny’) it could open up challenges to controversial gun control laws (like waiting periods) which have survived largely unscathed over the past few years.

Even Heller itself (widely celebrated by Second Amendment supporters) left some big ambiguities when it comes to the legality of gun control. The majority judgement of Justice Scalia, for example, appeared to confirm the legality of gun bans in government buildings and ‘sensitive places’: up until now, the Court hasn’t had to explore the meaning of these secondary remarks.

While it might not sit easily with red-state Second Amendment types, there’s an interesting parallel between gun control and another ethical and legal humdinger which will inevitably come before the Court before long: abortion.

Ever since President Trump took the White House, partisans on both sides have breathlessly predicted that the Supreme Court will ‘overturn’ Roe v. Wade and open up a path to the criminalization of abortion at state level.

In fact, such a drastic departure from precedent is almost impossible: abortion, like gun ownership, is almost universally recognized as a constitutional right. What’s still up for debate, though, is the power of states and municipalities to restrict that freedom in pursuance of what they claim is a legitimate public good (i.e. public safety or the protection of life).

In arguing its case, New York City will claim that its stringent gun control laws are a proportionate response to a legitimate aim. And it will be up for the Supreme Court to decide whether that’s the case. If the majority feels it isn’t, it will strike down the law accordingly.

As an intellectual exercise, you can even take some of the gun-control/anti-abortion measures that get debated in the courts and imagine how they might work in the parallel case. There’s been lots of fuss, for example, about so-called ‘ultrasound’ laws, which dictate that any woman seeking an abortion must first be shown an image of the fetus. While lots of conservatives might support these laws instinctively, how would they feel if a liberal state made it compulsory to watch a short film about the dangers of guns (say, the likelihood of injuring your own loved ones) before buying a Glock? Would that be a proportionate public safety response, or a backdoor attack on the Second Amendment and freedom of conscience?

These are the kind of issues the Supreme Court has to grapple with: not the headline question of whether Americans should be own a gun (or access a termination) at all, but the right of states to balance this liberty against other aims. Come this fall, those questions could be about to get very interesting.