Japan’s longest-serving Prime Minister, Shinzō Abe, has announced that he will step down, as soon as his replacement is selected. This is the second time that Abe has resigned the premiership (the first being in 2007) and ill health has again been cited as the reason. Abe has visited hospital several times in recent weeks and has looked tired on his rare public appearances as his chronic bowel disease has recurred.

The news has sparked two debates — the first, urgent one, is over Abe’s successor. The front-runner is probably Shigeru Ishiba, the 63-year-old former defense minister and Abe critic. The hawkish Ishiba is relatively liked by voters, but is less popular with his LDP colleagues; a serious obstacle. Former foreign affairs minister Fumio Kishida, also 63, is allegedly Abe’s preferred choice, despite not sharing his mentor’s dream of revising Article 9 of the pacifist constitution: renouncing war.

Other possibilities are Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga (71), also known as ‘Abe’s brain’, who could slither through on the inside. Or current defense minister, the combative and increasingly popular, Tarō Kōno (a mere 57) who is a rare fluent English speaker, educated at Georgetown University. Britain’s interests might be best served by Toshimitsu Motegi (64), the current foreign minister, who is up to speed on Brexit (he visited London recently for trade talks), and is seen as a good all round diplomat.

The outsiders include Shinjirō Koizumi, son of flamboyant former PM ‘lion king’ Junichirō Koizumi. At 39, he is a couple of decades too young and already scandal prone. And there is one woman in the field, Seiko Noda (59), a former internal affairs minister who now holds the nebulously titled portfolio of ‘women’s empowerment’. Few give her even a remote chance.

If Abe’s condition worsens, or he just decides not to hang around, then 79-year-old rakish, fedora wearing Deputy Prime Minister, Tarō Asō — and undistinguished former gaffe prone PM — could make an almost unbelievable return to the top job, albeit on a very brief interim basis. It could be fun to see the old boy back for a few weeks.

The second question is over Abe’s legacy, which will probably be seen as a mixed bag involving a lot of fine sounding initiatives that ultimately did not come to not very much — punctuated by regular scandals, many involving his unhelpful wife Akie.

It is generally considered that the much heralded ‘Abenomics’ — with three arrows of monetary easing, fiscal reform, and structural reform — were decent enough ideas in theory, but they ultimately fell flat as structural reform was hardly launched and two ill-thought through consumption tax rises scuppered growth.

His ‘womenomics’ campaign to improve female representation in the workplace achieved some concrete results (Japan now enjoys record female labor participation rates), but never really gathered momentum or even much public support — it looked like a Western notion that didn’t translate into Japan’s highly structured and traditional society.

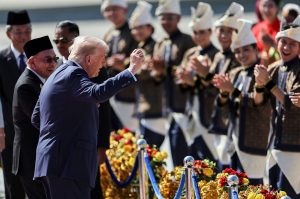

On the international stage, Abe invested in a relationship with Donald Trump, sharing hamburgers and a golf buggy on the Donald’s multiple visits; it’s debatable how much good this did him. There were ambitious plans for a reset of the relationship with China in the ‘fifth political document’, a roadmap for Sino-Japanese relations over the next 10 years, but COVID and rising Sino-skepticism stalled that. Relations with South Korea have been beset by the legacy issues of the ‘comfort women’, forced to work in Japanese brothels during World War Two, and are currently at a very low ebb.

As to Abe’s handling of coronavirus, he has received almost universally bad reviews, with limp performances at press conferences outshone by media savvy Tokyo governor Yuriko Koike, confused messaging, and unconvincing stunts like the dispatch of poor-quality face masks to every home in the country (immediately thrown away by almost everyone — though I retained mine as a souvenir). This judgement could be revised as the limited lockdown, minimal interference in private lives, and most of all, an extremely low death toll, is relatively positive compared with elsewhere.

***

Get a digital subscription to The Spectator.

Try a month free, then just $3.99 a month

***

Abe’s most significant legacies might be the least understood. As Tobias Harris notes in his recently published biography, Abe considerably strengthened the power of the prime minister’s office, assuming executive power for the appointment of top bureaucrats and gaining more control over the release of state secrets. And via a set of state security laws, Abe has enabled Japan to give aid to the USA in wholly unprecedented ways. He has also overseen a significant regrouping in the habitually faction ridden Liberal Democratic party, Japan’s seemingly eternal party of power.

Despite his best efforts (dressing up as Mario at the Rio Olympics), Abe was never an especially popular PM. I once wrote an article on the history of Japanese premiers titled ‘50 shades of grey’ (there have been around 50 in the post-war era) and Abe generally lived down to the dull, bureaucratic stereotype.

He had hoped that 2020 would be his year, with the Olympics a springboard to a potential fourth term. In the end, beset by scandals, accusations of COVID incompetence, waning popularity and now ill-health, it has all faded away.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website