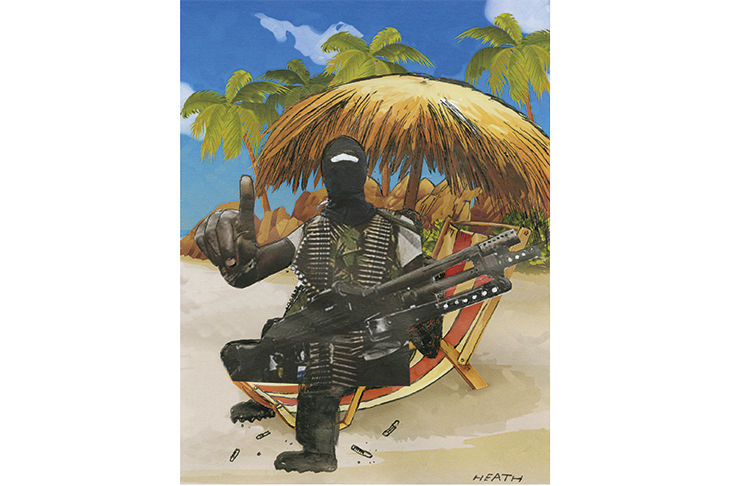

Brian Austin, a fisherman from the small village of Cedros in Trinidad, is struggling to describe the men who robbed him out at sea last year. ‘They had guns, they wore T-shirts and hoods.’ Then he brightens: ‘Have you ever seen Somali pirates? They looked just like that.’

I have indeed seen Somali pirates, as it happens, and rather closer up than I’d have liked. Ten years ago, a bunch of them kidnapped me for six weeks while I was out reporting. That was in Somalia, though, a failed state where anything goes. I never expected to be writing about a plague of pirates here in the Caribbean.

The last lot of Caribbean Blackbeards were hunted down by the Royal Navy about 300 years ago, bringing to a close the so-called ‘golden era’ of piracy. That was also that for buccaneering havens like Tortuga, where, according to legend, outlaws lived in egalitarian harmony, equably divvying up their pieces of eight.

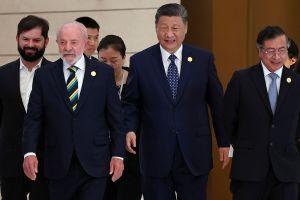

Oddly enough, the pirates that robbed Mr Austin are also denizens of a progressive paradise — or one that purports to be progressive. The new Pirates of the Caribbean are impoverished fishermen from nearby Venezuela, where the meltdown of the socialist regime long championed by Jeremy Corbyn means banditry has become one of the only ways to make a living.

The Venezuelan coastline lies less than 10 miles from Cedros, and used to be home to a thriving fishing industry. Today, thanks to hyperinflation and a disastrous nationalization program imposed by the late Hugo Chávez, Venezuela’s fishing industry is in ruins; most fishermen are jobless and their families scavenging to survive. It’s not quite Somalia, but it isn’t far off.

In lawless ports like Guiria in the Venezuelan state of Sucre, the pirates operate with near impunity, kidnapping Trinidadian fishermen and holding them for ransom. They also smuggle boatloads of cocaine and guns into Trinidad. Guns and coke are two commodities still widely available in Venezuela. On the return run, the pirates bring back the ordinary provisions that are in desperately short supply in their home country: nappies, rice and cooking oil. Think Narcos with speedboats and packets of Pampers.

Unlike their Somali counterparts, who ranged far out to sea and hijacked Greek shipping magnates’ cargo vessels, the Venezuelan pirates aren’t bashing the rich. Mostly, they stick inshore, targeting fellow fishermen like Mr Austin, who are themselves struggling.

‘The area around Cedros is becoming a haven for pirates, drugs and guns,’ says Mr Austin. ‘And who pays the price? The ordinary hardworking fisherman, of course.’

In fact, the tide of lawlessness from Venezuela spreads far beyond the beaches of Cedros. The influx of drugs and guns from Venezuela has been blamed for the worsening of gang wars in Trinidad’s slums, many of them now extremely violent. Last year, 500 people were murdered in Trinidad, total population only 1.3 million.

In Trinidad, I met a man called David ‘Buffy’ Maillard, a reformed gangster turned community worker who told me that the amount of marijuana, cocaine and heroin in the country has increased exponentially over the past three to five years. ‘The market in black weapons is now absolutely saturated,’ he said.

Drug crime is something Mr Maillard knows plenty about. An ex-bouncer, he once worked for a Jamaican gang in Miami, who specialized in robbing other drug dealers and taking their cocaine. After three gunshot wounds, five stab wounds, and numerous stints in jail, he embraced Islam, and works to get Trinidad’s gang members to mend their ways. Yet even in his bad old days, he’d be small fry compared with some of the villains across the water in Venezuela.

Coverage of Venezuela’s slide into anarchy tends to focus on its economic horrors: how the country has run out of toilet paper, or how people now treat themselves with animal medication bought on the black market from vets, because the hospitals have been cleaned out. What’s mentioned less often is that the chaos has fueled the rise of parastatal smuggling groups, like the Cartel of the Suns.

Named after the emblems worn by top brass in the Bolivarian National Guard, the cartel is made up of high-ranking Chavista generals and politicians who became involved in trafficking Colombian cocaine when Chávez first took power. Thanks to Chávez’s decision to kick the Drug Enforcement Agency out of Caracas in 2005, the power of the narco generals in Venezuela is virtually unchallenged.

Today, nearly half of all cocaine shipments bound for Europe come through Venezuela. In the past five years, Washington has sanctioned numerous alleged cartel members on suspicion of drug-trafficking, including the heads of the National Guard, the former head of military intelligence, and an ex-vice president. In 2017, two nephews of President Nicolás Maduro’s wife were also jailed in New York for a $20 million trafficking plot, allegedly aimed at keeping the first family in power. The whole thing is reminiscent of Colombia in the days of Pablo Escobar, only this time the traffickers are in government.

If most of Venezuela’s cocaine goes to the West, its black-market weapons are a different story. They tend to stay in the region, supplying not just Trinidad but the whole of the Caribbean and Latin America. Thanks to Chávez, there is a near-limitless supply.

In 2006, at the height of his paranoia about a US invasion, Chávez signed a deal with Russia to create a Kalashnikov manufacturing plant in Venezuela, and also bought 100,000 brand-new Kalashnikovs — far more than his armed forces needed. Vast quantities of guns have since been distributed to pro-Chavista colectivos militias, ostensibly to defend la revolución from a Yankee-backed overthrow.

But these colectivos inevitably drift into crime. As InSight Crime, a foundation dedicated to Latin American security issues, puts it: ‘The disintegration of the Venezuelan state and its total corruption has far-reaching regional implications for criminal dynamics.’

Over the New Year, Britain’s Defense Secretary, Gavin Williamson, announced that a post-Brexit Britain will set up new naval bases in both the Caribbean and the Far East, ‘creating a deterrent’ to piracy and other maritime mischief. But as we saw in Somalia a decade ago, all the navies in the world are little use when the pirates have a safe haven to bolt to. Foreign naval patrols would also need Caracas’s permission to enter territorial waters. It is very unlikely to give it.

A more likely outcome is that little neighbors like Trinidad are left to deal with the fallout from Venezuela themselves, relying on their underfunded and overwhelmed police forces. Already, Trinidadians are worried about the recent influx of an estimated 40,000 Venezuelan émigrés, a few of whom are involved in the drugs and weapons trade. The UN has lectured the island for carrying out deportations, irking its prime minister, Keith Rowley, who has said he ‘will not allow UN spokespersons to convert us into a refugee camp’.

Back in Cedros, Mr Austin has given up fishing altogether, and is looking for a less dangerous job. He may find it hard. At Cedros’s ferry terminal down the road, 150 new Venezuelan refugees arrive each week, many of whom are likewise seeking work.

Most fear that things are going to get much worse in Venezuela before they get better. Last week, Maduro — Chávez’s plodding successor — was sworn in for another six-year term, having won a rigged election last May. The refugees might note, though, that there is apparently one bright spot on the economic horizon for 2019. The new Kalashnikov plant, capable of churning out 25,000 rifles annually, is finally due to open this year.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.