A dirt road empties out on the highway outside Midland, South Dakota, just past the dense fields of sunflowers, their yellow-petaled faces turned west to follow the late August sunset.

There’s nothing remarkable about the road, I suppose. It’s just another of those Midwestern right-of-ways, running down the section line so the farmers and ranchers can reach their fields: hundreds of miles of straight-line highway pavement, intersected here and there at right angles by the dozens of miles of straight-line dirt tracks.

But each of them is also a path cut through the landscapes off to the side — an arrow aimed not at the horizon beyond the windshield but at an unknown country: the distant hills that mark the horizon in a different direction. And every once in a while, you wonder what that land is like. Every once in a while, you imagine turning to follow that dirt track up into the far hills.

But you don’t make the turn. Or, at least, I didn’t this time, driving across the prairie from the Black Hills to the lake country along the Minnesota border and stopping in Midland for lunch.

A South Dakota town roughly halfway between the Badlands and the Missouri River, Midland is pretty much the epitome of flyover country — instantiating (did anyone flying over it know) the great unconscious symbol, the Jungian archetype, of the Middle West. The settlers may have come seeking a new home in the wild, but — good Scandinavians, for the most part — they decided they would be tidy while they were about it. Like nearly every South Dakota town, Midland has streets laid out true to the compass, the water tower and the church steeples the only spikes that rise above the rooflines of the neat one-story houses.

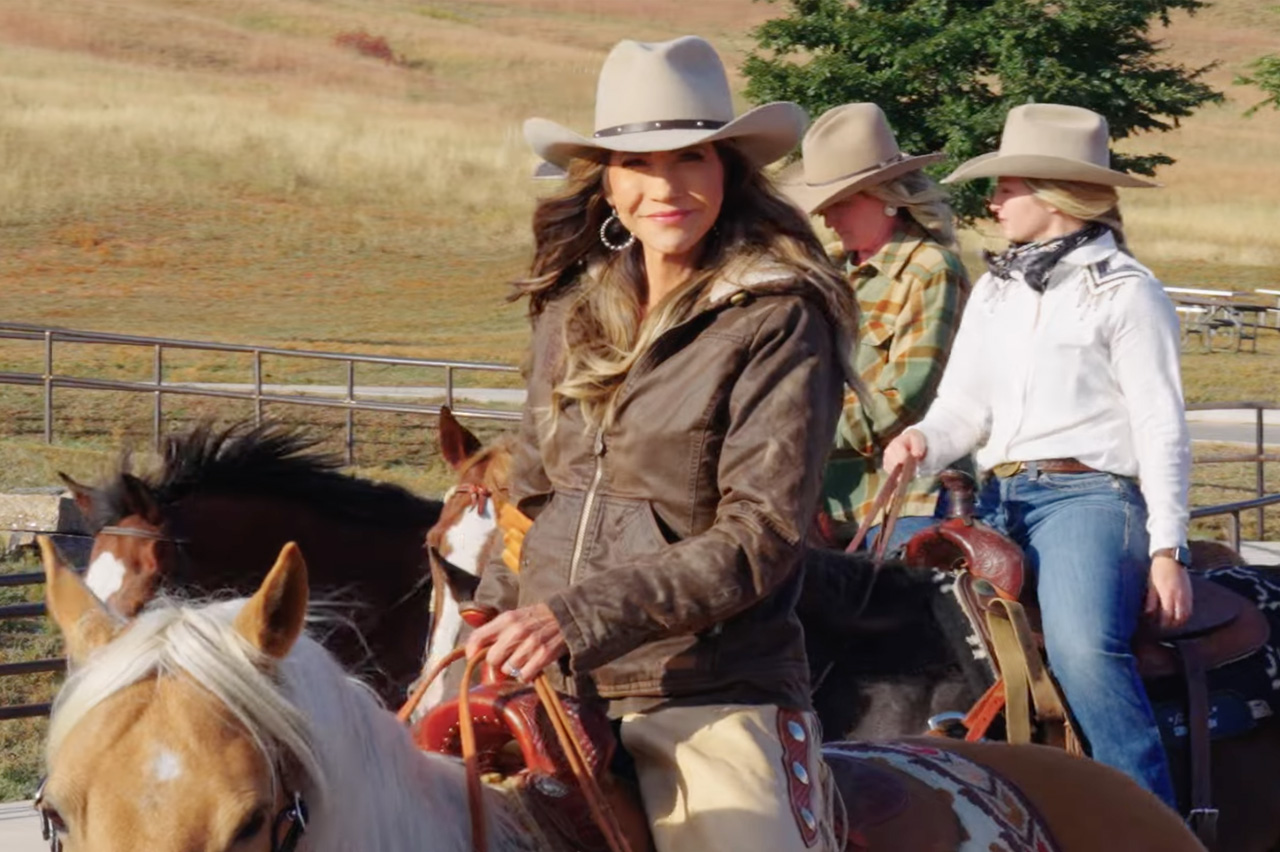

This isn’t the Rust Belt, mostly because, unlike the towns around Pittsburgh or Detroit, there was never all that much industry to be abandoned and fall to rust. It’s just 150 people or so living in a nice little town little changed since it was laid out in 1890. Like every municipality across the prairie, the lawns are dotted with a few political signs: ‘Kristi Noem for Governor — All in for South Dakota!’ and ‘Dusty Johnson for Congress.’ But not all that many signs, and none that I could see for Democrats.

For that matter, conversations in diners were much more interesting before the primaries. As late as 2004, all three of South Dakota’s officials in Washington (two senators and a single member of Congress) were Democrats. But these days, the state, like much of the West, has become essentially a single-party enclave. The Republican primary in June was the real election.

The conversations I leaned back to overhear in Midland — in the state capital of Pierre, and over in Madison, on the eastern side of the state — were more about next month’s opening of pheasant-hunting season than they were about elections. Politicians come and go. Only God and the weather are sure to endure, out on the prairie.

Still, there’s no escaping the endless agitation that surrounds Donald Trump and the national media-political complex. Politics is done best when politics matters least, and the best proof that we’re doing politics poorly is how seriously and emotionally people seem to be taking it.

That’s even true, to a small but still significant degree, in the towns of the Midwest. I have a principle I offer from time to time: When you think your ordinary political opponents are not merely mistaken but actually evil, you have ceased to do politics and begun to do religion. And every time I say it, most everyone nods in agreement, as though to say, ‘Yes, isn’t it a shame.’ But then, when the conversation starts up again on the national scene, they return to talking of their ordinary political opponents in moral terms drawn from condemnations of Stalinists and Nazis.

Fortunately, that seems limited to discussion of events in Washington, DC. Nobody in South Dakota I’ve met speaks of Timothy Bjorkman, the Democratic nominee for Congress, or Billie Sutton, the Democratic nominee for governor, as evil. Just as destined to lose.

We’ll have to wait to see what happens once a Senate seat returns to the ballot in 2020 and the presidential race heats up. I sometimes wonder, though, how many Midwesterners are thinking about voting for Libertarian candidates. Or the Constitutional party. The Greens or the Socialists. A return of the old Progressives or the Grange. Maybe the Temperance party. Something different, anyway. Something like a turn off the tired old two-lane highway, to seek an unknown country up a dirt track toward the distant hills.

Joseph Bottum is director of the Classics Institute at Dakota State University.