Japan’s COVID ‘State of Emergency’ is now officially over. Tokyo, the last of Japan’s 47 prefectures to be officially released from restrictions, was declared safe(ish) on Monday, meaning its cautious three-step program of reopening all commercial premises and entertainment venues can begin.

The war over corona may have been won here, but with a host of competing theories and interested parties hoping to claim credit, the battle to decide how it happened is just beginning.

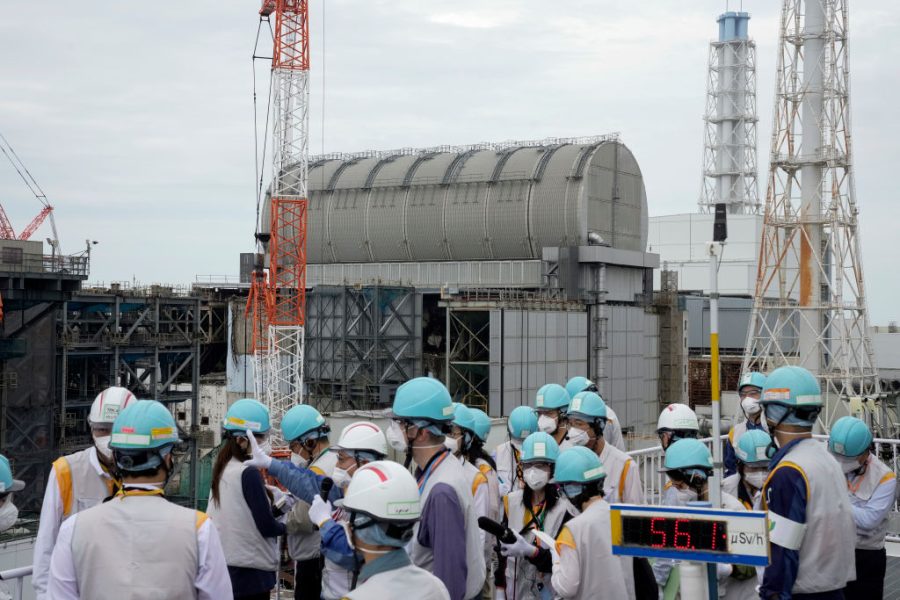

Japan’s official death toll from COVID-19 has not yet reached 1,000. This is in a country of 126 million people with densely packed cities, where people live a cheek-by-jowl existence on public transport, in compact offices, snug bars and restaurants, and tiny living spaces. This remarkable outcome was achieved in a country with no center for disaster control and which ignored the ‘test, test, test’ mantra of Britain’s Matt Hancock and his equivalents across much of the rest of the world.

Yes, there was a lockdown, of sorts, but it was all a bit phony. Major department stores closed, shrines and parks were cordoned off, and most, though not all, chain coffee shops, cafes and restaurants either shut or only serving takeout. But the bustling and narrow shotengai (local shopping arcades) that lead to the stations, and through which most people will walk at least once a day, remained just as bustling as ever, which made a mockery of official attempts to encourage social distancing through the ‘Three Cs’ approach (avoid closed spaces, crowded places, and close contact).

So what happened? TIME magazine lists some of the most prominent theories, as well as some of the wackiest. A rapid response contact and trace system is claimed to have been in operation in Japan, though I neither saw nor heard any evidence of it. With hardly anyone actually tested and no significant outbreak clusters of the virus, you wonder as well who they were actually tracking and tracing.

Nor should we assume that the measures taken were done with any degree of efficiency or effectiveness (Japanese administrative competence is one of the quainter and most enduring myths about the country). I sauntered through Haneda airport at the end of March after arriving from plague-ridden London and set off a thermal scanner in the process (because I was overdressed, I suspect, rather than ill). I was paid absolutely no heed by officials whatsoever. I duly complied with the guidance to self-isolate for two weeks, but no one checked that I was actually doing so.

Other theories for Japan’s success include the generally superior health condition of the Japanese, particularly their extremely low levels of obesity, their better hygiene, rather chaste social customs (no hugging or kissing), compulsory flu shots, the culture of mask wearing, and even the idea that the Japanese language, with its profusion of hard consonant as opposed to sibilant sounds, emits fewer potentially infected droplets — thus saving lives!

Another possibility is that the Diamond Princess cruise ship incident gave early warning of the disease and prompted the Japanese to make small but perhaps significant lifestyle adjustments, which may have proved effective in keeping the virus at bay at an important early stage. It’s also theorized that the Asian version of COVID-19 was never as strong as that faced in Western Europe.

It may also be that the figures are simply misleading — to the point of worthlessness. With so few tests carried out, it could be that Japan grossly underreported its number of cases, although it may have more accurately recorded the number of definitive COVID-19 deaths. Perhaps millions of Japanese did contract the virus, with mild or no symptoms, and simply recovered. Who knows?

As Japan doesn’t have ravenous tabloids, desperate to terrorize the public with wild and often highly dubious death toll and case number figures, there was less appetite here for reckless exaggeration. This helped calm nerves and may have stopped politicians from taking excessive action.

***

Get three months of The Spectator for just $9.99 — plus a Spectator Parker pen

***

This is all guesswork though, and while there may be some truth in some of these theories, I wonder if the reason Japan suffered less is essentially: none of the above.

I’m reminded of old primitive societies, where sacrifices were made to ensure good harvests. If good harvests ensued, it was assumed the sacrifices had been effective, and if not, that more or different sacrifices should have been made instead. With no obvious causative link between the actions taken by governments around the world and the results achieved, there may be something of that ancient superstition at work in our analysis of the COVID-19 panic/crisis. And perhaps all our theorizing reveals is that mankind’s arrogant belief that we can control the forces of nature is an eternal one.

Nature will do what it will do, and there’s not a whole lot we can do about it. The Japanese know that better than anyone.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.