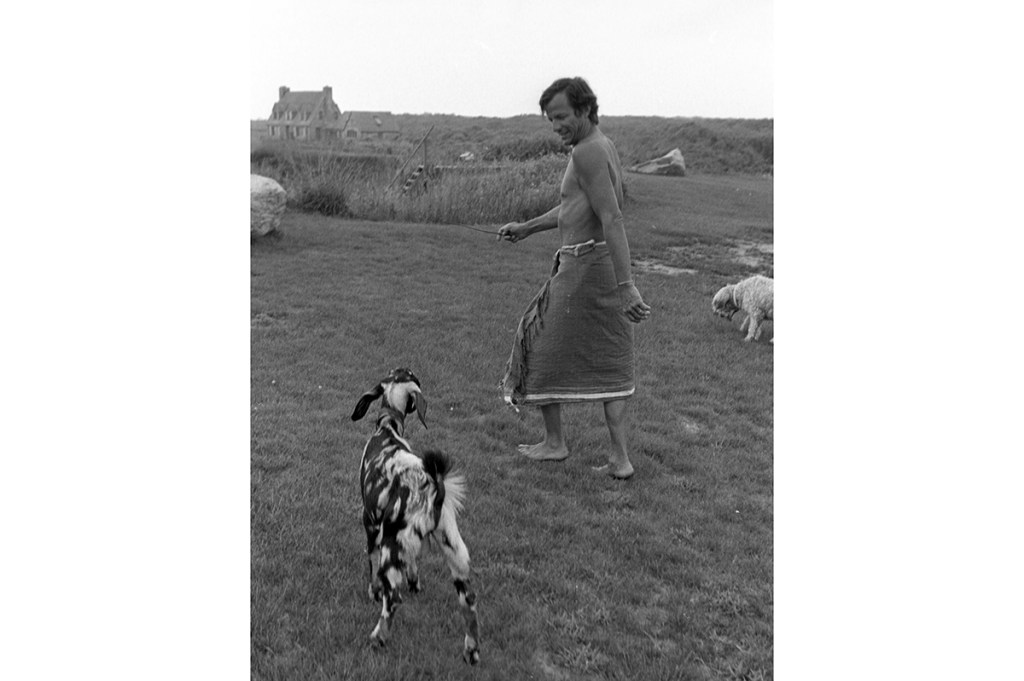

My family friend Peter Hill Beard, that hybrid of Hemingway, Warhol and Errol Flynn, died with signature irregularity sometime in either March or April, aged 82.

The obituaries say he was ‘known as “the last of the adventurers”’ so often that one suspects he may have coined that himself.

Peter was old money. His great-grandfather James Jerome Hill, born in 1838, founded the Great Northern Railway and from him descended a line of New York stockbrokers with a mansion on the Upper East Side and an estate in Tuxedo Park. William Waldorf Astor and J.P. Morgan attended Peter’s grandparents’ wedding. His grandmother later married Pierre Lorillard V, whose family were the original developers.

No financier, Peter became a photographer, focusing on his beloved Africa. Always trying to get the shot others couldn’t — in 1996 he was gored by an elephant — he developed a signature style of collaging the original image with handwritten notes and color washes, often using materials from the moment the photo was taken, such as elephant dung or his own blood. His works, enhanced by his personal cachet, sold well in exhibitions and from his friend Michael Hoppen’s gallery in London’s Chelsea.

Beginning as an African conservationist — a word he hated for evoking ‘tourist’ — Peter published his most important book in 1965, The End of the Game. But it was befriending Karen Blixen of Out of Africa fame and buying the neighboring ranch to hers in Kenya that created his African name.

Peter traveled the world, attending bullfights with Picasso and cafés with Dalí. He swanned around New York with Jackie Bouvier’s sister on his arm, and his second marriage was to the model Cheryl Tiegs. He had a countercultural streak and was a regular at Studio 54, even appearing in a film along with Andy Warhol.

Peter came into my family’s life fresh out of Pomfret School in Connecticut. He was 18 years old and had already visited Africa for the first time with the explorer Quentin Keynes, nephew of the economist and great-grandson of Charles Darwin. Sent to England to gain a little Old World polish, he boarded, on Keynes’s advice, at Felsted School in Essex, where he met my father, Clive, and his siblings.

Peter spent his holidays at our grand old family house. My family were a wild bunch with a penchant for gunplay, nominally hunting duck in the marshes but frequently ‘peppering’ one another, by accident or design. Peter shot my father. But then again, so did my uncle.

Peter went on to Yale and my father to Cambridge, but they remained in touch. Peter always sent postcards from his travels and copies of his books as they were published. He even attempted a joint book with my great-uncle Major Eric Dutton, an ‘old Africa hand’ who had been private secretary to the governor of Kenya.

I first met Peter in 1976 when he came for dinner at my father’s house in London. I don’t remember it, being under a year old, but I did hear how afterwards they went drinking at Harry’s Bar in the West End with a teenaged Caroline Kennedy, and how she and Peter slipped out before the check arrived to run laps barefoot around Berkeley Square.

When I arrived in New York City in the late 1990s, Peter was the first person I called. We met in Float, the popular nightclub of the time. I found him holding court at a table, with a model 40 years his junior by his side. Throughout the night, the men of the moment joined us for 15 minutes at a time, paying homage to the maestro before moving on before he became bored. I remember the now-disgraced Hollywood director and producer Brett Ratner and the magician David Blaine, fresh from performing for Nelson Mandela in his hotel.

Peter recounted his meandering life and philosophy with scatter-gun intensity. He was generous and gregarious but also imperious, with an edge. He asked after my grandmother, whom he recalled as having ‘the manners of a countess, but with a sense of humor and a taste for Scotch’. By then she been dead for several years. I now wonder if the exquisitely connected Peter had discovered the family scandal: her brief youthful marriage to a widower Italian count before returning to England to marry my grandfather.

He was most interesting on Africa, from where he had recently returned. Thirty-five years after The End Of The Game, he was even more fatalistic and depressed about its fate. In retrospect, leaving Africa was a massive blow to Peter. It not only removed his artistic inspiration but perhaps also the authentic core that justified the hedonism that comprised the rest of his life.

‘When I bought Hog Ranch,’ he said, referring to his estate bordering Blixen’s, ‘I was deep in the bush. When I sold it, it was a suburb of Nairobi.’

***

A print and digital subscription to The Spectator is just $7.99 a month

***

I saw Peter a few more times on that visit. He seemed to have developed a nostalgia for England: ‘It made me, that year at Felsted and with your family, it really did.’ He was helpful, too. When my girlfriend and I needed money, Peter’s contacts made us ‘pickers’ on the VIP section’s purple rope at a new nightspot — only to find out it was owned by John Scotto, son of the infamous Tony Scotto of the Gambino crime family.

After I left New York, I had a couple of exchanges with him but we never met up. He asked after my father but, both of them being of a reticent generation and a certain amount of water having passed under the bridge, neither picked up the phone.

Given the long periods — months at a time — he spent trekking out into the bush, Peter’s death was synoptic of his life. His body was found after a two-week search. Having suffered from dementia, he had walked deep into the wilderness near his shingled Montauk house. I can’t imagine a better way for him to have gone.

This article is in The Spectator’s June 2020 US edition.