We’re supposed only say good things about the dead—‘De mortuis & c.’, as one of John Buchan’s heroes manfully abbreviates it. It’s an ancient superstition, apotropaic and illogical. I’m with the Archdeacon in Anthony Trollope’s The Last Chronicle of Barset: the taboo is ‘founded in humbug’, so why adopt the ‘everyday decency of speaking well of one whom one had ever thought ill’? The deceasedness of the deceased means we can say what we really thought of them. It’s not going to hurt their feelings, is it?

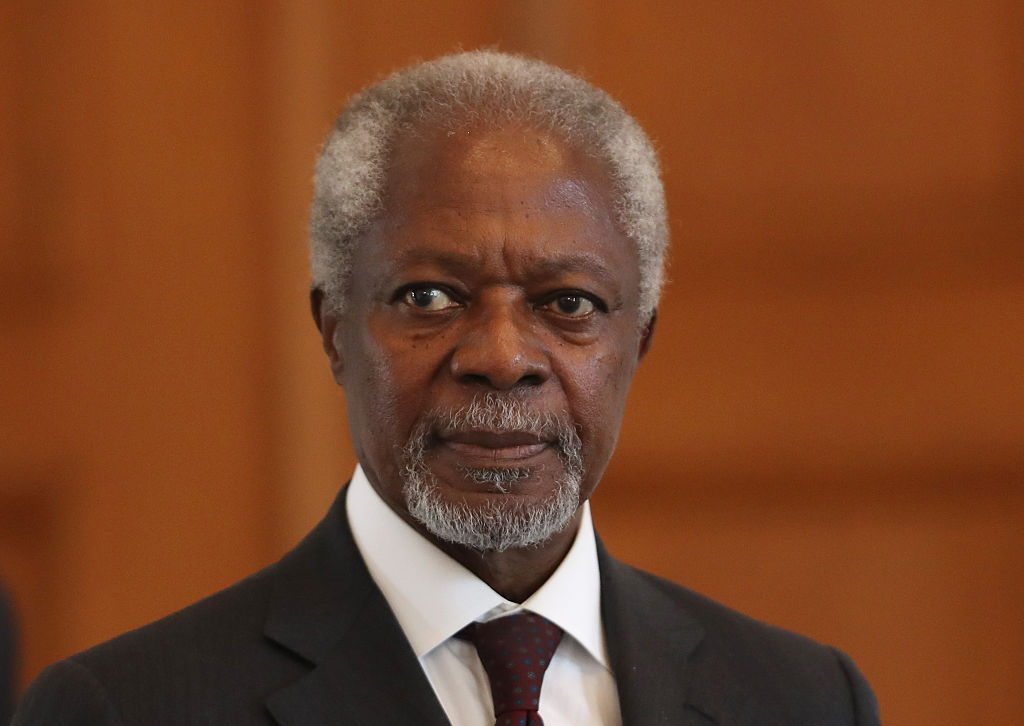

I ask because Kofi Annan fell off his perch over the weekend, aged 80 in a Swiss clinic. Annan was secretary-general of the UN for two terms, from 1997 to 2006. In 2001, he and the UN shared the Nobel Peace Prize, presumably after a Norwegian negotiating team had worked out whether to cut it in half or to apportion it according to the number of employees. After the UN, he joined The Elders, a group of superannuated diplomats who tour the world like the Traveling Wilburys of conflict resolution.

I have two things to say about Kofi Annan. One of them is what Keith Richards said when asked for his feelings about the death of Diana, Princess of Wales: ‘I never knew the chick.’ The other is that Kofi Annan seemed polite, well-dressed, and a complete waste of space.

No disaster, war of famine was complete in the 1990s without Annan turning up just after things had got completely, irretrievably and tragically out of control, in order to warn dolefully to the cameras that things were about to get completely out control, and that it would be irretrievable and tragic when they did. He was the conscience of yesterday’s news. He was the opposite of an early warning system. If Kofi landed at an airport near you, it was time to run for the hills, or form a militia.

Annan was the first secretary-general to be appointed from inside the UN bureaucracy. His path to the top came through the departments of human resources and budgets — the nether regions of the UN where, as Michael Ignatieff has noted, ‘nepotism and mismanagement are notorious’. Annan proved his fitness for the top job in 1994 when, as head of the UN’s peacekeeping operations, he failed to prevent the Hutus’ genocide of more than 500,000 Tutsis in Rwanda. In case anyone though this was a one-off, Annan repeated his folly the following year, by failing to prevent Bosnian Serb forces from killing more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslims at Srebrenica.

A quick study, Annan lobbied volubly for NATO airstrikes in Bosnia later that year. In 1996, the Clinton administration, unwilling to allow the Egyptian Boutros Boutros-Ghali to stay on for another term, pushed Annan as its candidate, and kept pushing through four French vetoes. It was the late Nineties, and the liberal interventionists were about to have their way. In 1999, Annan called intervention on humanitarian grounds ‘a hopeful sign at the end of the 20th century’. It might be met with ‘distrust, skepticism, even hostility’, but it was ‘an evolution that we should welcome’.

He was out of his depth. The American response to 9/11 split the Security Council, and the more Annan appealed to the ‘international community’, the more the resulting silence suggested that no such thing existed. In 2003, Annan, who in 1998 had described the génocidaire Saddam Hussein as ‘a man I can do business with’, was describing the US-led invasion of Iraq as a war crime. In 2005, an inquiry into the Iraq oil-for-food program, the biggest UN humanitarian operation yet attempted, cleared Annan of doing the wrong kind of business with Saddam. Meanwhile, Annan’s son Kojo was working for Cotecna, a Swiss company that won UN contracts worth $4.8m in 1998. Move along, nothing to see.

In celebrity retirement, Annan became chairman of The Elders, an all-star team of chronic windbags whose star players were Jimmy Carter, Desmond Tutu and Mary Robinson. The funding for this pontificators’ supergroup came from deep diplomatic thinkers like Richard Branson, Peter Gabriel, and that tireless agent for global change, the Dutch Postcode Lottery. The assumption is that the passage of time has made these clapped-out camera-chasers not just geriatric, but wise. Annan, though soft-spoken, made it very clear that he had learnt nothing from his earlier failures to prevent genocide, by entangling himself in the Syrian Civil War as a UN special envoy, and then in the brutal business of a founding Elder, Aung San Suu Kyi of Myanmar.

When the Elders were founded in 2007, Aung San Suu Kyi’s chair was left symbolically empty, because she was in prison in Myanmar. By 2016, she was the de facto ruler of Myanmar, and ordering its army to mount a ‘counterinsurgency’ against the Rohingya Muslims under her rule. Under foreign pressure because of reports of widespread rape, murder and expulsion—a UN rapporteur had used the words ‘ethnic cleansing’—she suggested that Annan’s charitable foundation make a report.

Annan toured the country with a panel of nine advisers, six of them from Myanmar and none of them Rohingya, because they were not citizens under Myanmar law. He issued an anodyne report—he was ‘deeply concerned’, and appealed for the army to act ‘in full compliance with the rule of law’—and left. The killings, rapes and expulsions continued.

In 2002, Samantha Power wrote that Annan’s name will forever be associated with two outbreaks of mass murder. Power is an expert on this sort of thing, as her name will forever be associated with the slaughters in Libya and Syria. But Annan proved her wrong. His name will forever be associated with four outbreaks of mass murder: Rwanda, Srebenica, Syria, Rohingya. But he did seem friendly, and he was always well dressed.

Dominic Green is Life & Arts Editor of Spectator USA.