The Japanese government has announced a state of emergency for Tokyo, Osaka and five other prefectures in response to escalating numbers of coronavirus cases. It comes after prolonged pressure was exerted by politicians, healthcare professionals and outspoken governor of Tokyo Yuriko Koike. The measures are intended to last a month and come with a six trillion yen ($55 billion) compensation package to help affected businesses. This was the first such announcement in the history of Japan.

A ‘State of Emergency’ sounds dramatic, but it actually has few practical implications for citizens. Local officials will be empowered to ‘request’ (interpreted as implying a very strong obligation) people to stay indoors as much as possible, but there are no actual penalties for those venturing outside needlessly. Schools set to reopen will stay closed, but most people will keep on working, albeit from home if they can.

The move runs counter to the general mood in Tokyo, where it remains quiet but calm, with no sense of impending doom in the air. The streets may be largely empty and the most famous shrines, usually thronged with tourists, deserted — ironically restoring their original function as places of peace and serenity — but the majority of stores are still open. And apart from a run on toilet paper and face-masks, there is no evidence of panic buying in the supermarkets, which remain well stocked.

A sound truck comes round in the morning with a gentle reminder to stay in if possible, but it’s all very polite and respectful, almost comically apologetic.

Some of Tokyo’s parks are taped off but there are few other signs of an ongoing emergency. The Tokyo 2020 Olympic bunting still flutters in the breeze and the official merchandise is still on sale. I’d say there was a great chance to purchase what could possibly become valuably anachronistic souvenirs here, except that the word is that to save trouble next summer’s (putative) games will still be referred to as the ‘2020 Olympics’ .

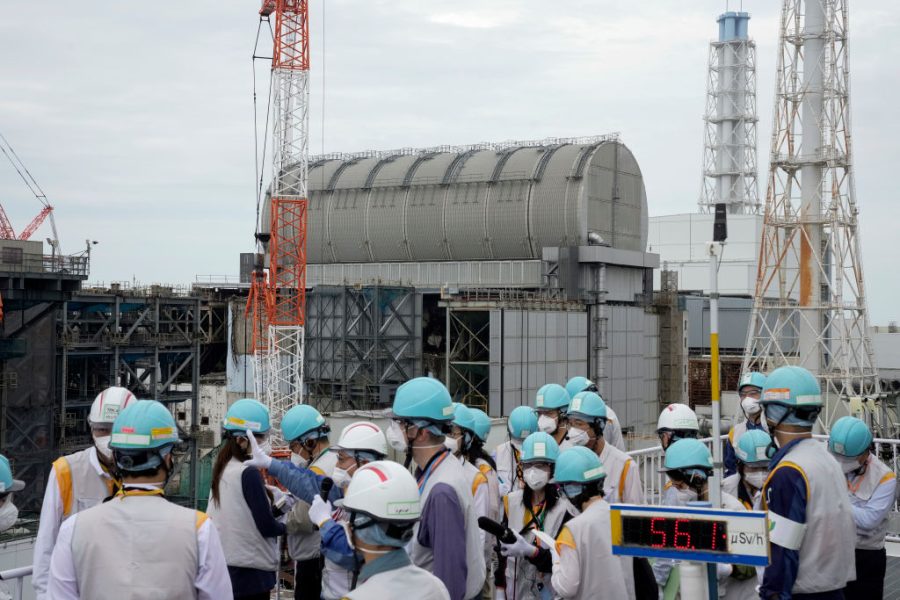

The lack of panic is characteristic and due, many would say, to the ingrained stoicism of the Japanese people, a result of a greater familiarity with natural disasters. It brings to mind the mood in the far more visibly dramatic days following the 2011 tsunami and Fukushima nuclear disaster. Then we had regular and violent after shocks, blackouts, food shortages, and the prospect of a cloud of radioactivity enveloping the capital. But people just got on with things then too.

Or perhaps it’s a purely rational response to the still relatively low numbers of infections and deaths here. The media have been urgently reporting the rising number of infections, but the number, and that of fatalities is still tiny when compared to Europe. The biggest story so far has been the COVID-19 related death of comic legend and national treasure Ken Shimura, 70, which abruptly pushed the Olympics postponement off the headlines.

The state of emergency declaration appears to be a precautionary measure against a possible collapse of the health care system if the number of cases were to surge. One real power that will be available is that local authorities will be able to requisition land for to build temporary medical facilities, if this becomes necessary.

But it is also, surely, a gesture, designed to make the government look determined and resolute. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe hasn’t been having an easy to time of it recently, and has looked weak on occasion, especially when contrasted with the dynamic performances of Tokyo governor Koike.

Abe was criticized for hanging on to the Olympic dream too long, even beyond the point when countries pulling out had made a postponement inevitable. And his chaotic COVID-19 press conferences held in tightly packed rooms have made a mockery of the social distancing advice he then delivered. He has even been accused of prudishness for excluding sex workers from the compensation package for freelancers.

It is not all Abe’s fault. He has been embarrassed, yet again, by his gaffe prone wife, Akie, who is alleged to have held a sneaky cherry blossom party with her friends despite these being strongly discouraged (Abe has denied she did so). Akie’s alleged politicking at last year’s official prime ministerial cherry blossom party was an almighty scandal, so you’d think she might have learned her lesson.

But the Akie Abe story is an exception. The strong sense of civic responsibility of the Japanese, coupled with tightly packed neighborhoods where nothing much goes unobserved, and a police box every couple of blocks, is ensuring that most people behave sensibly. There is no hotline for snitchers.

All of which makes today’s announcement look just a bit over the top.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.