Making a diagnosis used to be a well understood and practiced procedure: take a history from someone presenting with symptoms, examine them and do some tests to arrive at an overall diagnosis. It requires substantial training and experience to put this into practice. William Osler, known as one of the founders of modern medicine, often directed his trainees to ‘listen to the patient, he/she is telling you the diagnosis’.

With COVID-19, however, clinical diagnosis is seemingly a secondary consideration in the face of mass testing. All you require is a positive PCR test; no symptoms, no signs, no other diagnostic proof. But our limited understanding of mass testing and PCR suggests this might not suffice.

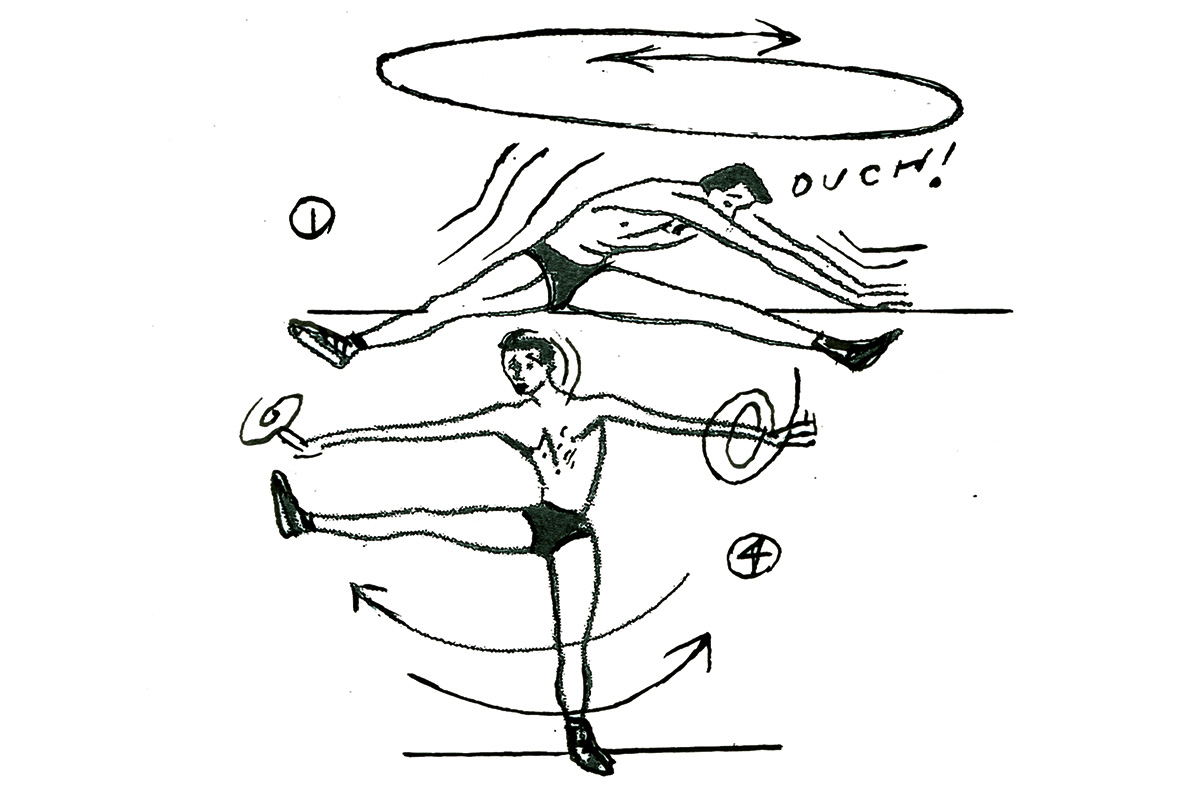

Detection of viruses using Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is helpful so long as its accuracy can be understood: it offers the capacity to detect RNA in minute quantities, but whether that RNA represents infectious virus is another matter. RT-PCR uses enzymes called reverse transcriptase to change a specific piece of genetic material called RNA into a matching piece of genetic DNA. The test then amplifies this DNA exponentially; millions of copies of DNA can be made from a single viral RNA strand.

A fluorescent signal is attached to the DNA copies, and when the fluorescent signal reaches a certain threshold, the test is deemed positive. The number of cycles required before the fluorescence threshold is reached gives an estimate of how much virus is present in the sample. This measure is called the cycle threshold (Ct). The higher the cycle number, the less RNA there is in the sample; the lower the level, the greater the amount in the initial sample.

In a recent BMJ rapid response, doctors in Wales set out these problems when using the PCR test when there is low viral circulation in the population. Routine testing found 26 low-level positive results for SARS-CoV-2. The number of cycles required to reach the threshold in these patients ranged from 36 to 43. Nineteen of these weakly positive tests were repeated, and all 19 were negative on repeat testing.

The importance of the cycle threshold is shown in a Canadian study of 96 samples from SARS-CoV-2 infected patients that reported live virus was only detected when the cycle threshold was less than 24. The difference in a threshold might not look like much, but samples can differ by more than a million more copies of viral RNA per milliliter. Some of the testing threshold used is attempting to detect one viral copy in the sample, which further exacerbates the problems.

Out of the 19 individuals who tested positive, one had been PCR positive three months earlier and was also antibody positive. The immune system works to neutralize the virus and prevent further infection. The infectious stage lasts about a week. Inactivated RNA, however, degrades slowly: it can be detected weeks after infectiousness has gone. In one case, RT-PCR continued to pick up fragments of RNA until the 63rd day after symptom onset. The duration of fecal shedding of viral RNA in one patient was up to 47 days from symptom onset.

***

Get a digital subscription to The Spectator.

Try a month free, then just $3.99 a month

***

PCR detection of viruses is helpful so long as its limitations are understood; while it detects RNA in minute quantities, caution needs to be applied to the results as it often does not detect the infectious virus. This detection problem is ubiquitous for RNA viruses detection. SARS-CoV, Mers, influenza, Ebola and Zika viral RNA can also be detected long after the disappearance of the infectious virus.

Why does this matter? Because when it comes to COVID-19, insufficient attention has been paid to how PCR results actually relate to disease. The harms of false-positive results can be substantial: operations can be delayed or canceled; patients are kept in hospital, just in case; further testing is required; in some cases, it drives local lockdowns. The results of our recent systematic review on viral infectiousness indicate that cycle thresholds are essential to understand who is infectious, and consequently, the extent of any outbreak and for controlling transmission.

When it comes to dealing with this ongoing pandemic, it is clear that COVID-19 — and our limited understanding of it — is testing our decision-making skills to the limit when it comes to diagnosing infections. And without a better understanding of what test results really show us, it seems that while coronavirus is at a low prevalence in our communities, mass testing might cause more harm than good if the nuances of test threshold are not understood.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.