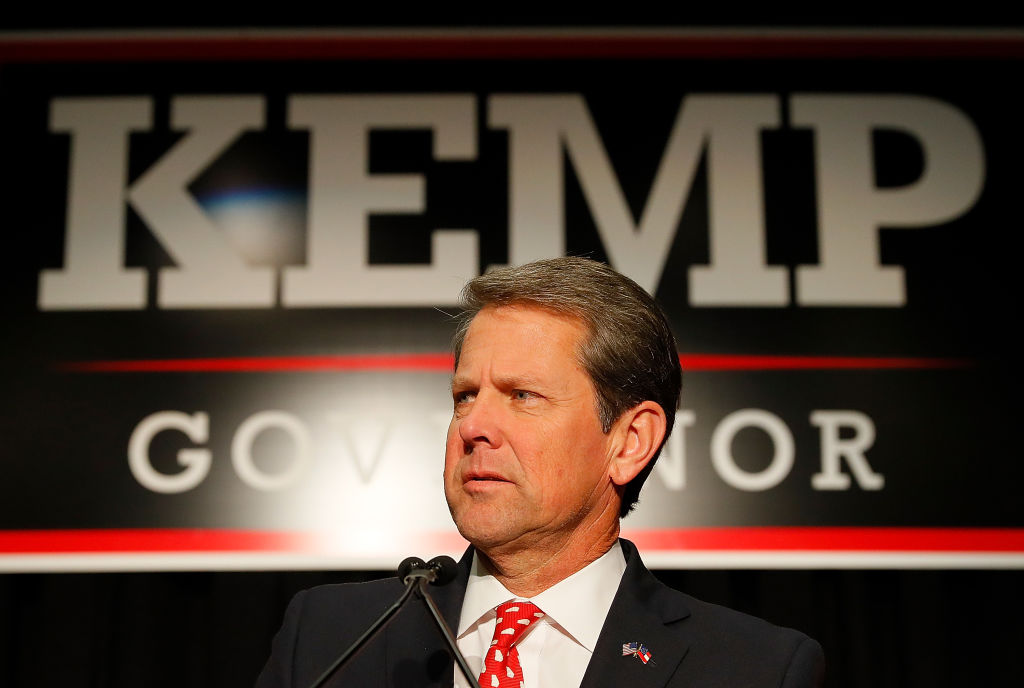

Georgians went to bed late on Election Day wondering if they’d wake up to a Groundhog Day in November: would the Republican candidate for governor, Brian Kemp, hold on to a slim majority, or would there be four more weeks of campaigning?

It took until after 9 a.m. Wednesday, but it appears the cold and bitter season known as the gubernatorial campaign is over. With 100 percent of precincts now reporting, Kemp has 50.4 percent of the vote. There could still be provisional ballots added to the total, but even if the same number of provisionals cast in 2016 were all counted for Democrat Stacey Abrams, Kemp would remain a hair over the majority threshold required to avoid a runoff. (Libertarian Ted Metz, who had embraced his role as a potential spoiler, won less than 1 percent of ballots.)

Now it’s all over but the shoutin’ – but there stands to be plenty of that.

Abrams ran her campaign on two main premises, overshadowing the normal back-and-forth over policy ideas.

One was that the way for a Democrat to win in Georgia was not to act like a kinder version of a Republican, or to rely on adults who’d never before even registered to vote. Rather, it was to take advantage of the strong antipathy on the left toward President Donald Trump, and try to run a presidential-year turnout model.

That premise was vindicated, even if Abrams came up just short. Hillary Clinton in 2016 won over half a million more votes in Georgia than Republican Gov. Nathan Deal did on his way to re-election in 2014, and Abrams won about 20,000 more than Clinton. Turnout in Georgia’s largest county, Fulton, came within 2.5 percentage points of the total from 2016; Abrams won the county handily. It was a similar story across metro Atlanta.

Abrams’s other main premise was a gift from her opponent. Kemp had spent the past eight years as secretary of state and hadn’t resigned before this campaign, as some but not all of his predecessors have done when seeking higher office. The upshot was that Abrams sought at every turn to portray Kemp as having undue influence over their contest.

Often, the claims against Kemp were off-base. For instance, during early voting and on Election Day, there were multiple reports about problems with polling stations and absentee-ballot requests. But these services are managed by county election boards, not the secretary of state’s office, and the places where the complaints were most numerous were in counties largely run by Democratic officials. In Fulton on Tuesday, where some of the highest-profile problems occurred and a judge ordered a handful of precincts to remain open up to three extra hours, a county official was the one who apologized for the mistakes.

Yet accusations Kemp mishandled tens of thousands of voter registrations are sure to persist. And judging by social media posts, there’s a significant contingent of people who believe anything that went wrong, or even might have, was due to machinations by Kemp.

In the interim, the Abrams team is almost certain to fight to ensure every provisional ballot is counted. It’s possible there are more than in 2016, although it would take about twice as many – with all going to the Democrat – to bring Kemp under 50 percent. Until then, and perhaps afterward, we will have to see if Democrats stoke anger and resentment about a ‘stolen’ election or offer a clean concession once every last vote has been tallied

In short, the elections groundhog may not have seen his shadow Wednesday morning, but the cloud overhead is unlikely to dissipate soon.

Kyle Wingfield is director and CEO of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation.