On a quiet street in Belgrade, a bronze statue of Confucius stands in front of a perforated white block, the new Chinese cultural center. This is on the former site of the Chinese embassy which in 1999 was bombed by US-led Nato forces during the Kosovo War. Three Chinese nationals were killed. The Americans said the bombing was an accident, but the deaths allowed China and Serbia to share a common anti-Nato grievance. This week, timed to coincide with the twenty-fifth anniversary of the bombing, Xi Jinping visited Belgrade and talked about the Sino-Serbian “bond forged with the blood of our compatriots.” He had been expected to visit the embassy site but seems to have decided that that would be too provocative against Washington.

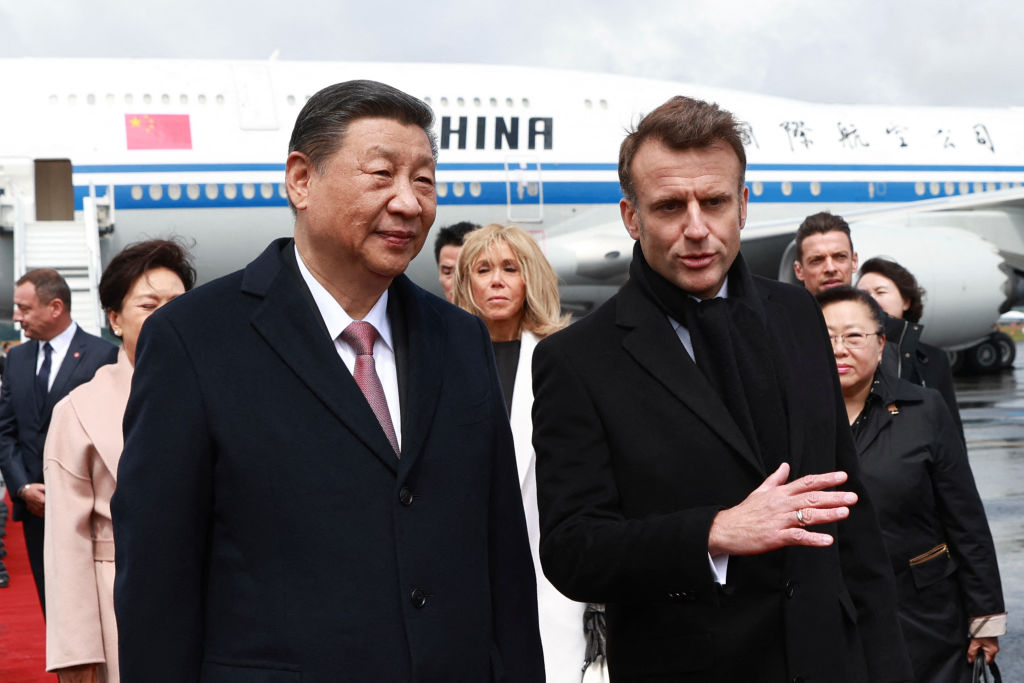

Xi has been on a week-long European tour and the countries he visited — France, Serbia and Hungary — could be viewed as some of the most Sino–sympathetic on the continent. Beijing’s relationship with France has become increasingly complicated as Chinese electric cars and solar panels compete with French manufacturers. Xi’s mission in Serbia and Hungary was more straight-forward: these have been two of China’s biggest cheerleaders in recent years.

China has spent more than a decade trying to woo Europe, beginning in 2012 when it set up an initiative called the “Cooperation Between China and Central and Eastern European Countries,” also known as “16+1” (a reference to the number of European countries that joined). The tactic was straight out of the Belt and Road playbook: charming less wealthy nations with cash and investment while appealing to a narrative of historical solidarity wherever possible. The aim is to peel central and eastern European countries away from the US-led world order and weaken claims of “western unity.” Various EU members such as Latvia, Bulgaria, Croatia and Slovakia were open to finding out what Beijing was offering. Five years ago, Greece joined, making it 17+1.

China had overpromised and by 2021 its partners had begun to back away. Lithuania was the first to leave, its foreign minister saying that belonging to the initiative had brought “almost no benefits.” Estonia and Latvia followed. They had good reason to be unimpressed: by 2020, most of the original sixteen countries had seen very little Chinese investment. The region’s trade deficit with China had, in fact, been going up, not down.

The pandemic further tarred Beijing’s reputation. The final straw, especially for the post-Soviet states, has been China’s unwillingness to condemn Vladimir Putin after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Poland and the Czech Republic have become some of China’s fiercest critics in Europe.

As Beijing loses support in the rest of Europe, those countries that remain loyal are lavishly rewarded

Unusually, Serbs came to view China in a more positive light during the pandemic, thanks to some PPE and vaccine diplomacy. Aleksandar Vucic, Serbia’s president, called the Chinese his “brothers” and lambasted “the fairy tale” of European solidarity after the European Commission limited exports of PPE to non-EU countries. When a million doses of the Sinopharm vaccines arrived in Serbia, Vucic kissed the Chinese flag on camera.

Similarly, when the Hungarian foreign minister, Peter Szijjarto, visited Tianjin last year, he called the European plan to “de-risk” from Chinese supply chains “brutal suicide.” It was more the sort of language you’d expect to hear from the Chinese foreign ministry. Hungary has also consistently used its EU membership to block anti-China policies. In 2016, it watered down a statement condemning Chinese actions in the South China Sea. In 2021, it vetoed another one criticizing the national security law in Hong Kong.

Covid, Ukraine, Chinese sanctions on European politicians and the influx of cheap Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) and solar panels have all contributed to worse relations with Brussels. Under Ursula von der Leyen, the commission has put in place new trade measures to investigate and punish Chinese offloading in high-tech industries. In the UK, news broke on Monday that Chinese hackers are thought to have targeted their ministry of defense, accessing the payroll data for most of the British armed forces.

As Beijing loses support in the rest of Europe, those countries that remain loyal are lavishly rewarded. China is the single biggest investor in both Hungary and Serbia. This week, Xi and Orbán are expected to announce a new EV production plant in Hungary. This will come after a Fujian-based battery maker committed $7 billion to building a new factory in the largest ever single tranche of inward investment in Hungary. It is expected to create 9,000 jobs. In Serbia, work began this year on a new China-backed stadium and a renewable energy deal worth $2 billion.

How long can Budapest and Belgrade hold out against the European mainstream? There are signs that anti-China sentiment is on the rise in both countries. Polls suggest that Hungarian opposition leaders, media and the population in general see China more negatively than positively. In Serbia, activists are speaking out about Chinese contractors’ poor labor practices and environmental record.

Xi has seen that the tide of political opinion can change quickly. All it can do is keep doling out cash incentives and playing up victimhood narratives.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply