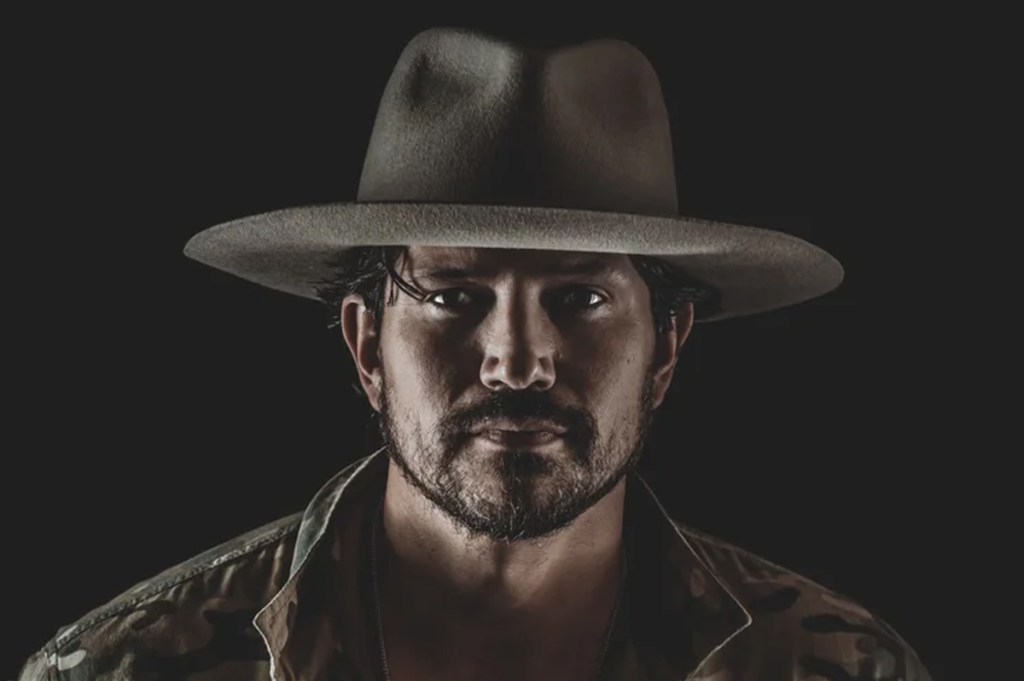

“I think the question that needs to be asked is: what kind of military does Canada even want?” Dallas Alexander has been all country-star cool until I ask about his former employer. Now his voice takes on a more earnest tone.

We’ve talked about the song the veteran-turned-singer considers his best – “Child of this Land,” a ballad about growing up in the remote Fishing Lake Métis Settlement in northern Alberta – and we’ve discussed which is the fan favorite: same, he says, or maybe the more upbeat “Can’t Blame My Bloodline.” To my mild surprise he doesn’t mention “Adios Amigo.” The song, with its catchy (and ominous) refrain, references the record-breaking sniper shot taken by Alexander’s team in 2017. Fired during the Battle of Mosul, the bullet traveled 2.2 miles before taking out an ISIS combatant who had just scrambled out of a window with an AK-47.

Back then, Alexander was a sniper with the elite Joint Task Force 2, a Canadian special ops unit on a par with America’s Delta Force and Britain’s SAS. But the Canadian Armed Forces were already beginning to lose their way, pursuing diversity, equity and inclusion at the expense of effectiveness – and only a few years later, Alexander would be hounded out.

Today, Alexander is unimpressed by General Jennie Carignan, the head of Canadian defense, who appeared on TV earlier this month with a tearful public apology for systemic racism. Alexander, who is Métis and served for 17 years, doesn’t think the military is systemically racist, as he understands the word “systemic.” He’s nuanced about it: racism, he says, can appear in any large group, especially in an aggressive workplace like a military unit or sports team, with “very get-after-it types of people.” But, “I don’t think the answer to any of it is a general – supposed to be in charge of a fighting force – crying on TV.”

It began when Alexander was still fighting with Joint Task Force 2. “It was starting to trickle in, you needed to do an Indigenous awareness course. And I was like, what the hell does this have to do with a special operations unit? And I’m Indigenous.” Gender awareness courses were next, then other sensitivity training, all eating into time previously spent on combat training.

The Canadian military has been struggling with recruitment and retention, and I remark that leadership seems to think that going down the sensitivity route will attract more people. “They’re going to get the people that they ask for, that’s all… recruiting might go through the ceiling,” but it’ll be “just a bunch of people that want to go in and be sensitive and get free money.”

When Covid hit, with its protocols and mandates, the troops felt they were being used as a testing ground; the government wanted to “be able to go to the world, or to the rest of Canada, and say: look, this group of people were 100 percent compliant.”

Alexander thinks that if every person in JTF2 at the time who didn’t want to be vaccinated had stuck to it, their unit might have gotten away with it. The government would have had to cancel the whole Tier 1 special operations program – and Alexander thinks that wouldn’t have happened. But there was a lot of pressure. “People got scared for their mortgages and their next positions.” Many caved; those who, like Alexander, held their ground were eventually forced out. He thinks the elite units took a gigantic hit at this point. “A lot of people that were very experienced in tons of operations, leaders, aggressive, what you need in a force like that,” left. “And like the cliché of an action movie, if I had to pick a team to go do some crazy mission, every single person I would add to that team is out of the military right now.”

How good was the Canadian military, before all this? “Second to none,” Alexander says of his unit. They trained and competed a lot with Delta in the US and though the Canadian special forces have nowhere near the same money and equipment, Joint Task Force 2 “kicked ass.”

If Canada wanted to turn things around, what could be done? “If I was in charge of the military in Canada tomorrow,” Alexander says, “I mean, this is gonna sound terrible, but I’m gonna say it anyway – I would cancel almost every part of the military and build a robust special operations unit and intelligence-gathering unit. And that is all that we would have. The rest would be volunteers to help within Canada. And that’s it.”

I ask him about PTSD. Alexander says he thinks a lot of veterans go through a similar cycle, becoming disillusioned when they “realize that the government… is corrupt and immoral.” He firmly believes soldiers need to know what their own morals are before heading out on deployment and “if someone tells you to do something against that, you tell them to go to hell.”

“Everyone says that’s not how the military works,” he says. But Alexander believes in morals. For him, they always came before orders. “Call me a bad soldier. I don’t really care. But I don’t have debilitating PTSD because I stuck to my morals.” He says a lot of young guys who go into the military early are put into situations for which they are unprepared. Then once they grow up, they have a lot of regrets that they have to work through. Moral preparation “isn’t popular because it makes soldiers harder to deal with. Instead of just taking some stupid order, you’re like, wait a minute… but I think it’s needed if you want to get out the other side and be able to sit peacefully at the dinner table with your family.”

What does Alexander think of the Canadian government offering euthanasia to vets asking for help with PTSD? “To me, that’s insane,” Alexander says. “It’s insane that that is a place where the government thinks it should be stepping in, offering to kill people who are its own citizens. I think it’s very weird. And especially people in vulnerable positions… it’s sickening.” Why pick on veterans in particular? “I mean, you look at it, it saves them a lot of money, that’s for sure. But I don’t know. It’s not a good enough reason, in my opinion.” Mine neither.

Alexander is pursuing his music career in Nashville now, where he’s making tour plans for 2026 and has founded Music City Gun Club for artists and musicians to go shooting with special operations instructors. He likes Tennessee. “I’m super happy and grateful for all that happened, because I’m way better off now,” he says. That said, speaking with Alexander, it seems to me that you can take the boy out of the country, but you can’t take the country out of the boy. Of his own songs, his favorite is “Child of This Land.” And that, in a way, says it all.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply