Conservative media seems to have missed this story, and the limited liberal press it got took it as a simple win. But the real showdown is coming this fall. Later this year, it is possible — not likely, but possible — that the Supreme Court will take away the right of social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook to censor content. This would have the effect of granting some level of First Amendment protection, now unavailable, to conservative users of those platforms.

The potential for change hinges on a law struck down by the lower courts, Netchoice v. Paxton, which challenges Texas law HB 20. That law addresses social media companies with more than 50 million active users in the US, like Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook. It prohibits these companies from engaging in content moderation by censoring posts on the basis of viewpoint. If a platform does remove any content, it must notify the user and let them appeal the decision. These users can sue the company for imposing “viewpoint discrimination.” HB 20 also bars platforms from placing warning labels on users’ posts to inform viewers that they contain objectionable content. It imposes disclosure requirements, including a biannual transparency report.

The law was shut down by the lower courts, then reinstated, then handed off to the Supreme Court as a shadow docket case (an informal term for the use of summary decisions by the Supreme Court without full oral argument). The Supreme Court refused to reinstate the law, but with significant dissent. The case will likely be heard in full by the Court in the fall. The conservatives will get another try.

Twitter, et al, acting collectively through trade associations, chose an interesting defense, claiming not simply that the First Amendment applies only to government censors (the standard defense to prevent First Amendment rights from applying to social media), but that their content moderation constitutes First Amendment-protected speech in and of itself. In other words, censoring stuff that passes through their platforms constitutes a First Amendment-protected act by Twitter, and thus HB 20 violates Twitter’s First Amendment rights. The platforms argued that laws like HB 20 constitute the government blocking Twitter’s free speech right to prevent its users from exercising their free speech rights, with censorship an act of free speech.

Twitter and its allies declared, “Social media platforms are internet websites that exercise editorial discretion over what content they disseminate and how such content is displayed to users.” That seems to rub right against Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which protects social media platforms from the First Amendment by claiming they aren’t really “publishers” after all, just something akin to a conduit through which stuff (your tweets) flows.

As such, the Communications Decency Act argues, they are closer to common carriers, like the phone company, which could not care less what you talk about in your call to Aunt Josie. But the common carrier argument comes closer and closer to implying that social media has no right to censor. In other words, they can’t have it both ways: they can’t not be responsible for defamatory material on their sites while claiming immunity from the First Amendment stopping them from censoring certain viewpoints. Imagine the phone company saying they are not responsible for you calling Aunt Josie a hag, but they also want to censor your conversation for using the “hate speech” term “hag.”

In other words, Twitter is either a publisher, and like the New York Times can exercise editorial discretion and is responsible for what it publishes, or it is not, and like the phone company cannot censor and is not responsible for its content.

In his dissent to the Court’s decision to stay HB 20, Justice Sam Alito (joined by Justices Thomas and Gorsuch; Justice Kagan also dissented but did not join Alito’s opinion or write her own) notes the indecision by Twitter, et al, on whether they are publishers, but says their desire to censor (i.e., to have First Amendment rights of their own) means they must be publishers. But if they want to insist they are not publishers, they are common carriers and do not have a right to censor. Pick one.

Alito is well aware of the recent history of social media censorship, which has egregiously sought to block and cancel nearly exclusively right-of-center persons. Facebook and others have become the censors the Founding Fathers especially feared, as one political party benefits disproportionately.

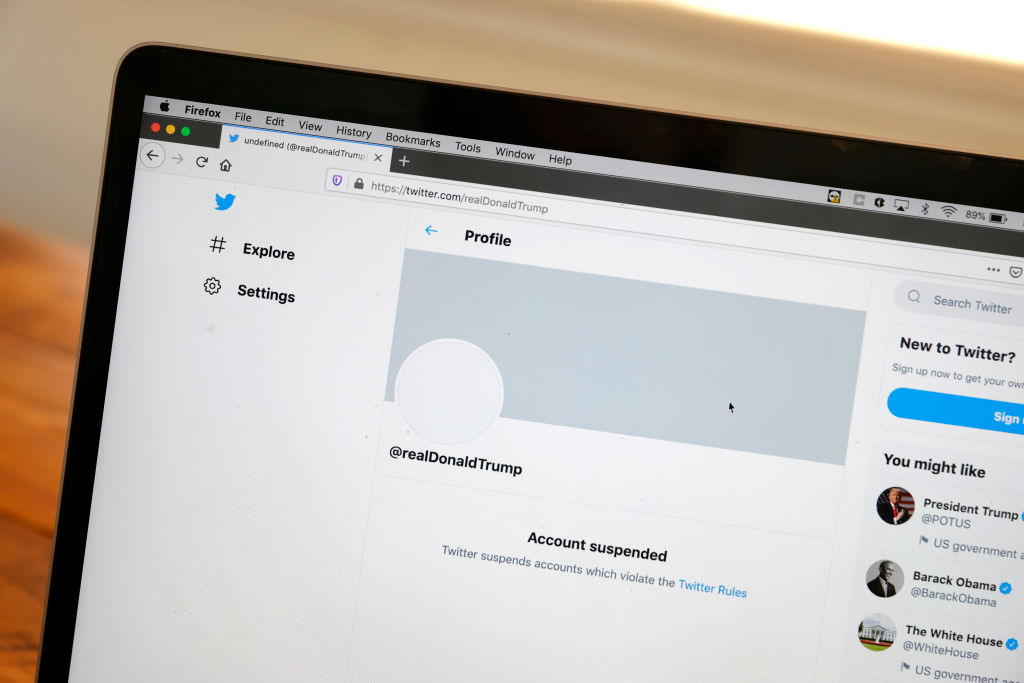

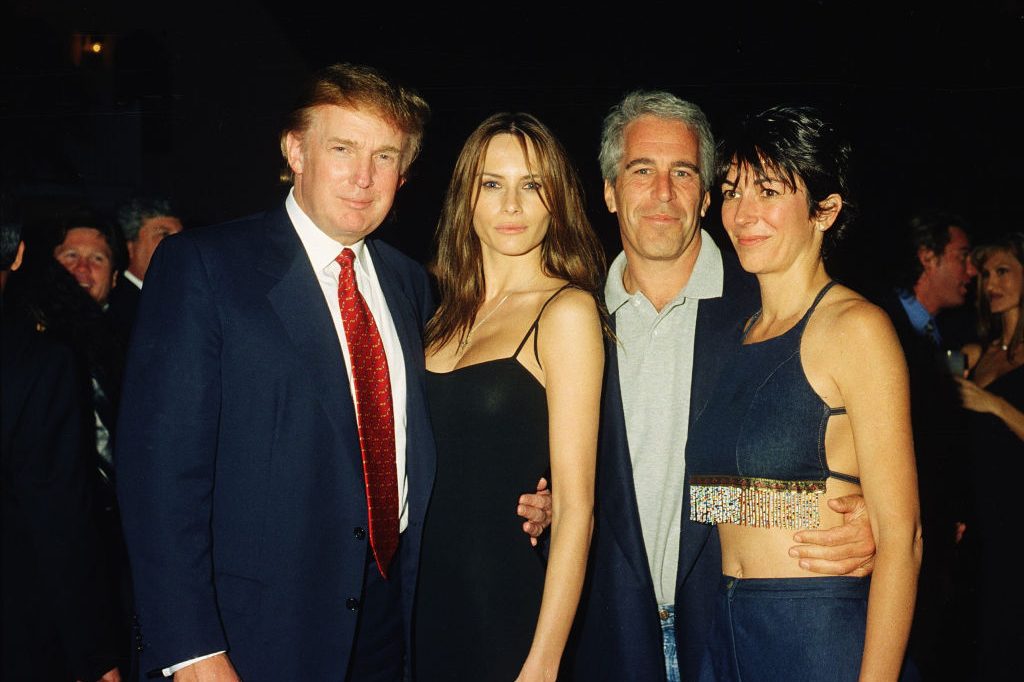

Donald Trump was driven off of social media as a sitting president. What should have been one of the biggest stories of the 2020 election, the Hunter Biden laptop imbroglio, was disappeared to favor Joe Biden. Social commentators like Alex Jones and Scott Horton were banned. Marjorie Taylor Greene was suspended. Of all the members of the House banned from social media, every single one is a Republican. Size matters; banning the head of the Republican Party, Donald Trump, and banning a local Democratic councilman in Iowa are not 1:1. What is being censored is not content per se (a photo, a news story) but whole points of view, in this case conservative thought itself.

Viewpoint discrimination is particularly disfavored by the courts. When a censor engages in content discrimination, he is restricting speech on a given subject matter. When he engages in viewpoint discrimination, he is singling out a particular opinion or perspective on that subject matter for treatment unlike that given to other viewpoints.

For example, if the government banned all speech about abortion, it would be a content-based regulation. But if the government banned only speech that criticized abortion, it would be viewpoint-based. Because the government is essentially taking sides in a debate when it engages in viewpoint discrimination and shutting down the marketplace of ideas — which is the whole dang point of free speech — the Supreme Court has held viewpoint-based restrictions to be especially offensive to the First Amendment. Such restrictions are treated as presumptively unconstitutional.

So when HB 20 comes before the Court as a full case with oral arguments in the fall, the lines are drawn. Twitter, et al, must appear ready to admit they are “publishers” (and likely loosen or shed the protections of Section 230) to retain a publisher’s right under the First Amendment to decide what to publish and, conversely, what to censor.

Alito seems to be suggesting that, if that’s the argument, then, yes, let the First Amendment apply. But it must apply to Twitter, et al, in its entirety.

So what are you, Twitter? You can no longer operate behind the illusion of democracy. Are you a dumb pipe, a common carrier, down which information simply flows? Or are you a publisher with First Amendment rights that you use to stomp out one particular viewpoint?

If the latter, HB 20 may be the needed relief to protect the modern town square, and the Supreme Court may approve its constitutionality this autumn.