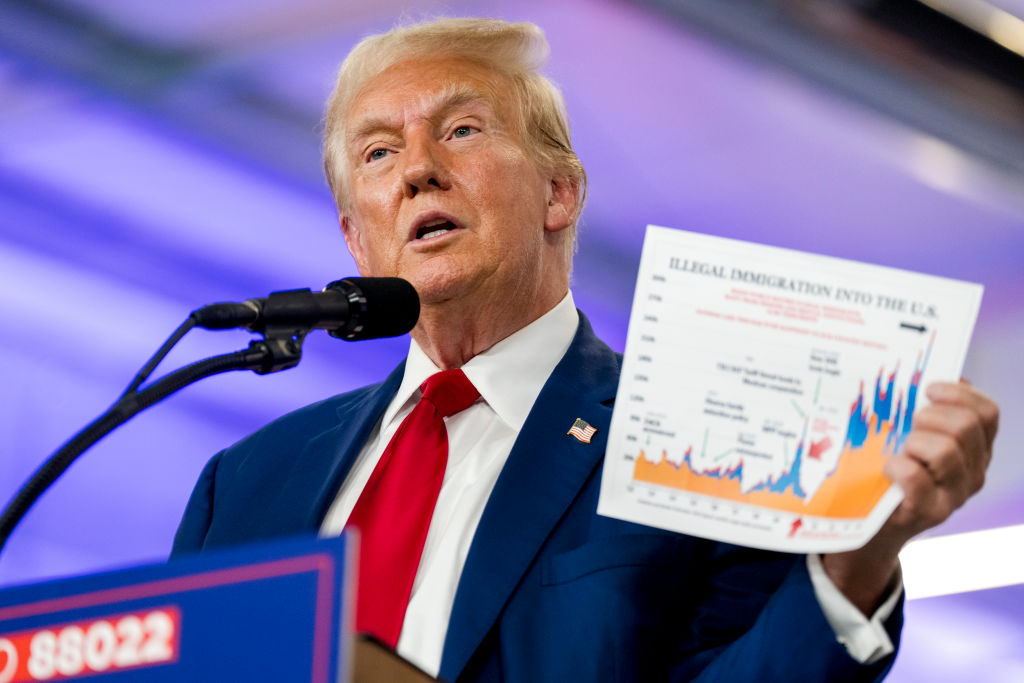

“Slowly at first, then all at once” is the most famous line Ernest Hemingway never wrote, and credit its fame to its accuracy. It might feel like naming the Mexican cartels foreign terror organizations, and passing a bipartisan Authorization of the Use of Military Force against them, is an idea taking hold in Washington at breakneck speed. But it’s been an item of discussion for years.

What’s causing it to finally break into the mainstream is the Biden administration’s lackadaisical approach to the fentanyl crisis along with the increasingly untrustworthy behavior of Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

The White House, for its part, rejects the idea. Daft press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre, who stated earlier this week that the status of fentanyl on the border has never been better, told reporters on Wednesday that “Designating these cartels as [foreign terrorist organizations] would not grant us any additional authorities that we don’t really have at this time,” and that “The United States has powerful sanctions authorities specifically designated to combat narcotics trafficking organizations and the individuals and entities that enable them.”

Of course, that dismissive, limp-wristed approach to the fentanyl crisis and the entities that fuel it is how we got where we are today. Asked yesterday about challenging the cartels with the American military even without the approval of the Mexican government, Texas Democratic representative Vicente Gonzalez said “we should consider every single option.” The Republican presidential field is quickly coalescing around the idea of a military response — as Phil Wegmann reports, every current GOP presidential campaign indicates that they support the FTO designation.

Mike Pompeo, whom I profiled last fall, noted in response to a New Hampshire voter that he had floated the idea while in office:

“CNN ran a piece — I think it was in somebody’s book, there’ve been so many books written — where President Trump was accused of saying he wanted to bomb Mexico. And I said, ‘No, that was actually me!’”

“Today the ungoverned space isn’t just in Afghanistan,” Pompeo continued. “It’s a stone’s throw from El Paso. There is no governing rule. There is no sheriff. The cartels are running the place and any law enforcement is on the take. This is deeply dangerous… How might we protect America from ungoverned space on our own border? How do you prevent Xi Jinping from moving drugs into America and putting our nation in decline? What are the tools we might have? And so we begin to think about how we might use the full range of America’s capacity to protect us from these ungoverned spaces. We should renew that.”

Crossing the line into the use of America’s armed forces is a significant one, but then the law enforcement approach has often proven insufficient to deal with the source of this deadly flood of fentanyl. As just one example, consider the situation of Mexico’s former defense minister, retired General Salvador Cienfuegos. A prominent man long suspected of taking bribes and working hand-in-glove with the cartels, in the fall of 2020 he was arrested by the DEA at Los Angeles International Airport.

What happened next? A research paper published last year by the Texas Public Policy Foundation, “Abrazos no Balazos? The Mexican State-Cartel Nexus,” tells the story:

Cienfuegos, who served as secretary of defense under Peña Nieto, was accused of assisting the nascent H-2 Cartel in moving thousands of kilograms of cocaine, marijuana, heroin and methamphetamines into the US. The evidence put forth by American prosecutors included confirmation that he was indeed the shadowy, powerful “El Padrino” figure and key H-2 contact whom the DEA had been trying to identify for months. Other sources added that Cienfuegos ensured “military operations were not conducted against the H-2 Cartel” and “initiating military operations against its rival drug trafficking organizations…

Mexico and AMLO himself demanded that the US hand back the general. The US begrudgingly complied, reasoning that “sensitive and important foreign policy considerations outweigh the government’s interest in pursuing the prosecution of [Cienfuegos]”. Upon Cienfuegos’ return, the Mexican government dropped all drug-trafficking and corruption charges against him. The Mexican state’s — and the Mexican president’s — deliberate blind eye to the body of evidence collected by US agents on Cienfuegos is a textbook case of government complicity in cartel-related corruption.

AMLO even took the step of releasing confidential files shared with the Mexican government by the DEA publicly, accusing the Americans of trying to frame the general and pronouncing their evidence “garbage.”

America cannot tolerate a situation where the peace of a border city depends on whether the cartels who direct drugs and human beings through it — in the case of Matamoros, the Ciclones and the Escorpiones — are getting along. The cartels need to have their capabilities degraded, and Mexican elites who profit from their criminal activity need to be punished. Anything less is deeply unserious.