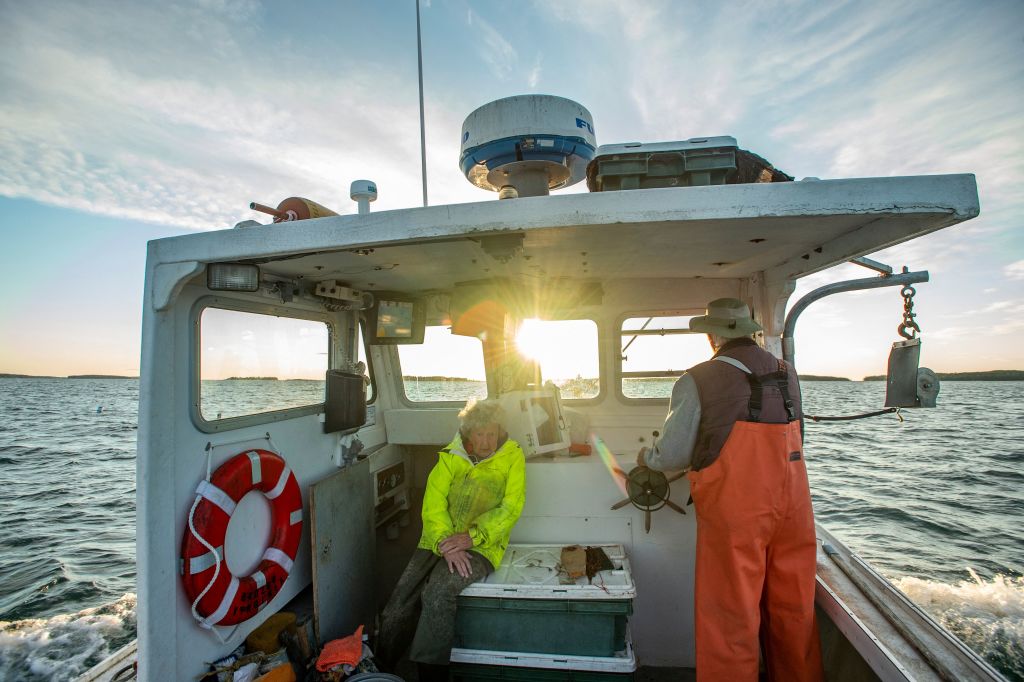

Chevron is dead. Many will mourn its passing. Forty is too young, they will say, for a doctrine to have done its work in enabling bureaucrats to decide for us the meaning of laws and the nature of reality. But the US Supreme Court has overturned Chevron in a landmark ruling in Loper Bright and Relentless, cases named after fishing boats which regulators drove toward extinction. It is appropriate, as Justice Gorsuch phrases it in his concurrence, that “the Court places a tombstone on Chevron no one can miss.”

The powers of the bureaucracy reined in by the new ruling may seem subtle or benign. The Chevron doctrine was that when the terms of a law are ambiguous, regulators in administrative agencies have the power to define the meaning of the law and its application. The doctrine relies on perceptions of ambiguity, which have expanded in recent years to be the norm rather than the exception.

Chevron was written in 1984 and championed by conservative Justice Antonin Scalia who joined the Supreme Court soon afterward. In the more innocent times of the 1980s, Justice Scalia still believed that words had meaning. This was before the appalling doctrines of postmodernism and deconstruction had truly taken hold. It was before so many people lied so openly about things we could all see for ourselves if we had the courage to speak of them before they were shown for a couple of hours on national television.

The now-dead doctrine had a two-step procedure. The first step was identifying any ambiguity. Scalia almost never found any in written laws. Words had meaning. But regulators and judges found more and more ambiguity, allowing them to move quickly to the second step which forced judges to defer to the judgments made by the bureaucrats unless their pronouncements were utterly unreasonable.

This two-step was always an unattractive dance, without a sexy outcome: the faceless bureaucrats decide for us. Under Chevron, regulators could decide one way, and later change their minds, but every time courts were told to defer to their judgments.

Loper Bright and Relentless are cases about whether regulators could decide whether the costs of observers on small fishing boats, who are paid to make sure the fishermen do not catch the wrong fish in the wrong amounts, would be borne by the government or the fishermen themselves. These costs are high, sometimes making a small fishing boat no longer profitable to send out. Assigning the costs to the fishermen may not be the most obvious interpretation of the statute, but as long as it was “reasonable,” courts under Chevron were bound to accept it. The fishermen did not, and the Supreme Court decided they were correct.

One of the most overlooked aspects of the Chevron doctrine was how it enabled government agencies to define disputed realities. In the original Chevron case, the dispute was whether a “stationary source” of pollution was a single piece of equipment or an entire industrial plant taken as a whole. We now must decide among perceptions of reality much more divisive, including who is a woman, whether new vaccines are safe or whether “systemic” racism is real. The broadest way to frame this constitutional controversy is: who holds the legitimate power to make such decisions about prevailing facts?

The claims to expertise made by the administrative state are simply no longer tenable. The dissent endorsed by the three liberal justices concludes with a quote from the original Chevron ruling that “judges are not experts in the field.” In more innocent times, the public trusted the professionals in administrative agencies to be honest experts, who would not misrepresent evidence, or hide data, or agree among themselves to lie for political goals. Recent events have shown that trust to be misplaced. The pandemic destroyed that faith, and we no longer trust when we can’t verify.

The Supreme Court has taken back the authority of judges to weigh evidence and decide if regulators have defined the terms of laws accurately and the conditions they regulate honestly. Legislators now have greater incentive to make decisions in the name of voters without defaulting on their responsibilities to bureaucrats. Accountability lies where it belongs with elected representatives, overseen by courts.

The death of Chevron is not merely about reining in the administrative state, but about who holds the power to recognize reality and identify prevailing facts. When our trust in government expertise died, Chevron relentlessly followed.