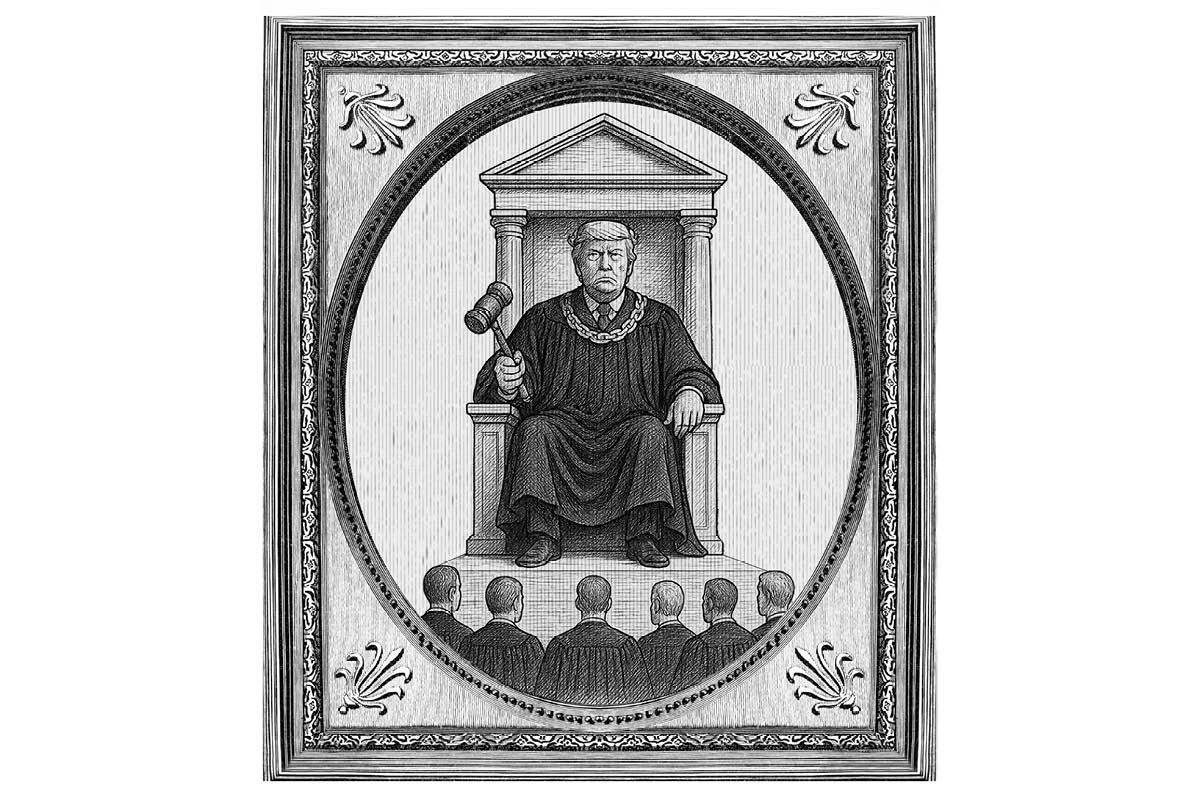

After consecutive Supreme Court terms with major rulings on abortion, guns and affirmative action, the justices don’t have anything on the docket now that will roil the culture wars. (The Trump ballot case to be argued as this goes to press will be a small blip.) Instead, this year our black-robed philosopher-kings are doing battle with the administrative state — which Steve Bannon promised to “deconstruct” when Donald Trump took office last go-round.

That shouldn’t be surprising; notwithstanding the media trope that Trump “stacked the court” to overrule Roe v. Wade, it was instead potential nominees’ commitments to reining in the bureaucracy that was White House counsel Don McGahn’s focus. Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh both made names for themselves fighting jurisprudential doctrines that put a thumb on the scale for the government in all its regulatory glory. And, of course, for interpreting legal text for its original public meaning rather than trying to divine some results-oriented legislative purpose. Amy Coney Barrett wasn’t a judge for long, but her opinions and academic writings put her very much in the mold of her mentor, Justice Antonin Scalia, who by the end of his life had also become quite skeptical of bureaucratic transmogrifications of congressional lawmaking. Parsing the arcane statutes and complex regulations that govern executive-branch agencies was once a rather sleepy, and very technical, area of law. But as people have come to realize it’s these agencies, rather than a grandstanding Congress, that increasingly make the laws that govern our lives, administrative law has come to the fore. As the Supreme Court has turned back expansive pen-and-phone schemes that range from “clean power” plans to vaccine mandates and student loan cancellation, you don’t have to own multiple green eyeshades to see that these lawyerly debates over agency power are a big deal.

In the fall, the justices heard arguments in big cases about 1) the funding mechanism for so-called independent agencies (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau v. Community Financial Services Association of America) and 2) the propriety of internal enforcement actions where, say, the Securities and Exchange Commission is the prosecutor, judge, jury and executioner (SEC v. Jarkesy). These are important issues that will affect how the “fourth branch” operates. But overshadowing even those major questions are two cases that will likely end — at least effectively — “Chevron deference.” That doctrine emerged from a 1984 Supreme Court ruling telling federal judges to defer to “reasonable” agency interpretations of statutes without bothering to discern what the best interpretation might be.

Loper Bright v. Raimondo and Relentless v. Department of Commerce both involve bizarre fishing rules. You’d expect the Court to use an obscure regulatory structure to change broader jurisprudence, rather than dealing with judicial-deference doctrines in the context of, say, transgender bathroom access (which the Court declined to take up). But these fishy cases with little apparent political salience still do well to illustrate the scale of the problem.

Family-run fishing businesses face a fraught and competitive environment even before the intrusion of burdensome regulations. The National Marine Fisheries Service promulgated a rule for herring boats that eventually nets most such businesses, as portrayed in the Oscar-winning movie CODA. If a vessel needs an onboard observer to monitor its adherence to regulations, and Congress has not budgeted enough money to pay for it, the fishermen must pay for one themselves. The cost for most boats exceeds $700 per sea day. Assorted fishing companies sued, arguing that the industry-funding requirement — which isn’t explicitly authorized by statute — will have a devastating economic impact that disproportionately affects small businesses.

The district court ruled for the government, finding that various provisions of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, or MSA, conferred broad authority to implement regulations to carry out fishery management. Without any analysis, the court also found that, even if the statute were ambiguous, the government’s reading would be reasonable under Chevron. A divided panel of the DC Circuit affirmed, reasoning that the MSA’s authorization of monitors left room for agency discretion.

Chevron deference rests on the presumption that Congress won’t over-delegate and that agencies will be loyal agents. But the past forty years have shown that Congress loves passing the buck and that agencies are actually principals who pursue their own interests (they’re prone to, say, protect their own budgets by passing costs onto citizens and those they regulate). I filed a brief in Loper Bright for the Manhattan Institute, joined by Professors Richard Epstein, Todd Zywicki, Gus Hurwitz and Geoffrey Manne — big names here — to argue that this experiment in rebalancing the relationship between administration and judicial review has failed. It has led to agency overreach, haphazard practical results and the diminution of Congress. Although it was intended to empower Congress by limiting the role of courts, Chevron has instead empowered agencies to aggrandize their own powers to the greatest extent plausible under their operative statutes, and often beyond. Courts, in turn, have become sloppy and lazy in interpreting statutes. It’s a vicious cycle of legislative buck-passing and judicial deference to executive overreach.

The time is ripe for a change, whether the Court uses these cases to overrule Chevron explicitly or keeps it nominally under a rewritten narrower standard. The Court did the latter in the 2019 case Kisor v. Wilkie, in which it preserved judicial deference to agency reinterpretation of its own regulations as devised in the 1997 case Auer v. Robbins. Kisor reworked Auer deference so completely that both Chief Justice John Roberts, who joined Justice Elena Kagan’s majority opinion, and Justice Kavanaugh, who joined Justice Gorsuch’s effective dissent, noted that there wasn’t much difference between Kagan’s explication and Gorsuch’s evisceration.

But don’t just take it from me (and the big-brain professors). After a long set of arguments earlier this year, at times both nitty-gritty and philosophical, it’s clear that a majority of the Court is unhappy with the current state of affairs. Whether the justices ultimately dump Chevron deference altogether or “Kisorize” it, we’ll be in a new world of administrative law. The smart money is that the Court will “end it, not mend it” because, as Roman Martinez, counsel to the Relentless fishermen, explained, the Chevron vessel is at this point encrusted with so many jurisprudential barnacles that adding even more would only further scuttle lower courts.

And as Paul Clement, counsel to the Loper Bright fishermen, who is considered to be the best Supreme Court advocate in the country, said in his argument, Chevron has fundamentally altered the incentives our elected representatives face, so that it’s impossible to legislate on major issues. One party or the other can just rely on its allies and appointees in executive agencies to accomplish its policy goals, which is a lot safer than making political compromises.

“We have major problems in society that aren’t being solved because, instead of actually doing the hard work of legislation where you have to compromise with the other side at the risk of maybe drawing a primary challenger, you rely on an executive branch friend to do what you want,” Clement said. “The kind of uniformity that you get under Chevron is something only the government could love because every court in the country has to agree on the current administration’s view of a debatable statute. You don’t get the kind of uniformity that you actually want, which is a stable decision that says this is what the statute means.”

Clement’s argument made a distinct impression; I jotted down “everyone mesmerized” on my notepad, while a friend across the viewing gallery wrote and underlined “captivating.” The justices were among those ensorcelled; Justice Gorsuch lamented that the doctrine may bear the name of a Fortune 10 behemoth, but that it’s “the immigrant, the veteran seeking his benefits, the Social Security Disability applicant, who have no power to influence agencies, who will never capture them, and whose interests are not the sorts of things on which people vote” who bear the brunt of legal doctrines that ensure the government almost always wins. You could be forgiven for thinking he was testing out material for the type of precedent-setting opinion that will be referenced for decades to come.

The Supreme Court should just tell lower-court judges to earn their pay by treating agency cases the same as any other, working to interpret even badly written statutes while holding the bureaucracy to the same standards as the citizens it regulates. That would be a whale of a tale — and it’s also what’s likely to happen come June, when the headlines will be about Trump, but it’s the administrative state that will be sunk.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply