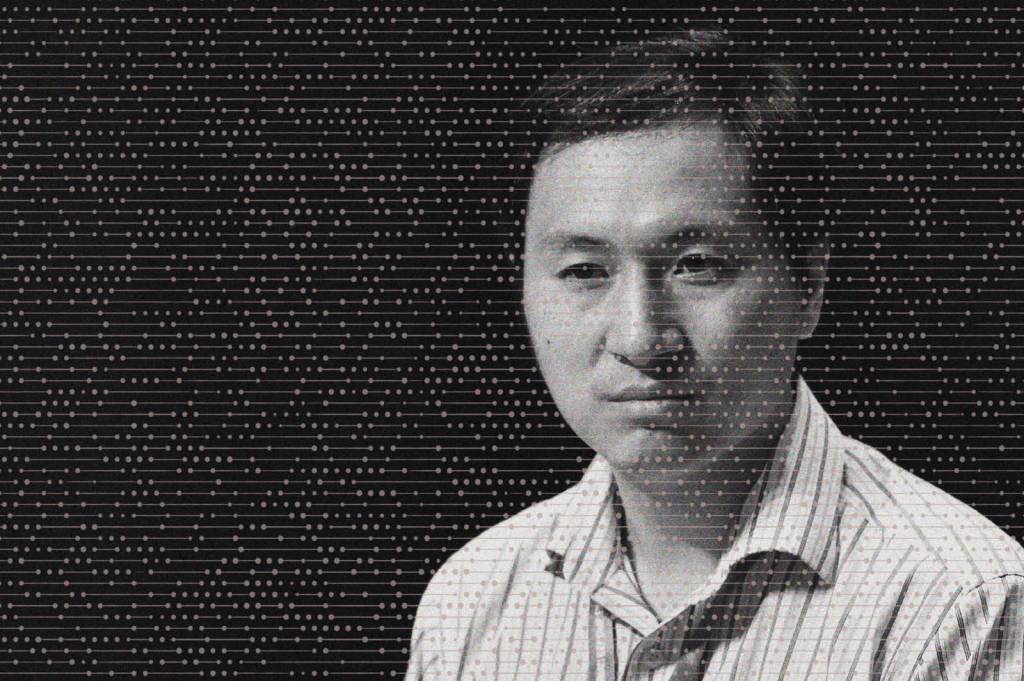

Before he agrees to be interviewed, He Jiankui has one request: that he is introduced as a “gene-editing pioneer.” This may come across as grandiose, but it is also indisputable. No one else in history, after all, can say they have created genetically edited human beings.

In 2018, He dropped the mother of all scientific bombs when he announced that he had used CRISPR, a gene-editing technique, to alter the DNA of two babies. In a YouTube video, He explained that the twins, “two beautiful Chinese girls,” codenamed Lulu and Nana, had been born safely just a few weeks before in Shenzhen. Both had had their embryos edited to prevent them catching HIV from their father. Later, it emerged that another woman was pregnant with a genetically modified baby. She gave birth to a girl in 2019.

With almost no debate or warning, a single biophysicist in Shenzhen had crossed a new line in scientific history. While he undoubtedly understood the significance of his discovery, it is obvious that He was unprepared for the fallout. CRISPR can easily damage other parts of a DNA strand, causing unknown effects that cascade down someone’s genetic code. He was accused by the scientific community of going rogue and risking the safety of the girls. After his experiment was made public, he was stripped of his university position and was sentenced to three years in jail by a Chinese court. In news reports around the world, He was labeled “China’s Frankenstein.”

It would not have been a surprise if that was the last we heard of He. Yet after serving his time, He revealed last year that he had opened a new laboratory in Beijing. He can’t say exactly where it is for security reasons, but it is funded by Chinese investors and donations. There is also potential American funding in the works and a plan to open another lab in Austin, Texas.

When we speak on a video call, He tells me that he will be researching Alzheimer’s, familial hypercholesterolemia — a genetic condition where the liver can’t process cholesterol properly — and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. He is not using human embryos, for now, but the direction of travel is obvious, even if he won’t implant a genetically altered embryo again, “until society has accepted it, and it becomes legal and ethically approved.” (In China, researchers can work on human embryos, but it is illegal to implant them using IVF.)

He believes that if he’s allowed to proceed with his experiments, it won’t be long before he can eliminate Alzheimer’s. He claims we can already pinpoint the exact genes to stop Alzheimer’s — there is a group of people in Iceland who have a mutation that prevents the disease. They live longer too. If this mutation were introduced into the general population, in theory we could eradicate Alzheimer’s and ensure it isn’t passed on to future generations. “Give me two years,” He says. “I’ll finish the experiment on the human cell line, mice and monkeys… So after two years, everything’s ready to go to human study, to human trials… And that’s also for the embryo gene editing.”

I ask about the girls with altered DNA. He tells me the twins are six and at elementary school in China. The third girl is being raised by a single mother. He claims they are “happy and healthy” and living normal lives. His team still has contact with the parents, but this is limited to protect their identities.

It is not entirely clear if the children will be resistant to HIV. In his experiment, He was attempting to disable a protein called CCR5, which the HIV virus uses to enter our cells. Of the three embryos he implanted, only one had the CCR5 gene fully disabled.

“[Nana] is completely immune to HIV for a lifetime. And another one is I would say half-immune, which means compared with normal people they have better protection but not complete protection.” Is Nana definitely fully immune to HIV? He says there was a plan six years ago to check her immunity using a blood sample, but the test was never performed. The samples are “still there in the refrigerator” but he doesn’t know if he can access them. “I hope that maybe one day we could continue to verify that.”

I point out that it wasn’t necessary to edit the DNA of the babies to prevent them catching HIV — there are treatments that hugely lower the risk of the virus being passed on. He argues the procedure was more about lifelong protection. He also says that in China there is a lot of stigma for those who have the virus: “When people know you have HIV, you lose your job. You may be forced to move out of the city. You may lose all your friends. So it’s hor- rible. It’s a social death.”

In 2019, a geneticist at London’s Fran- cis Crick Institute, Robin Lovell-Badge, pointed out that He had attempted to replicate a naturally occurring “delta-32” mutation in the embryos to block CCR5. But none of the embryos implanted had that mutation. Instead, they “harbor completely novel mutations, of which we have absolutely no understanding.” Asked about this, He argues that it doesn’t matter how the mutation was achieved: “So in the human population there are multiple ways to stop the CCR5 gene… It’s not necessary to do exactly the delta-32 mutation because the only thing is just stopping this gene.”

Researchers who have reviewed He’s data have suggested the babies may suffer from the genetic condition “mosaicism” — when a person has two or more genetically different sets of cells. This is something He rejects: “That’s a false statement… We did multiple tissue sampling and there’s no mosaicism. The results are perfect.” When were the tests carried out? “We did the genetic testing after birth and after that we’re not testing any genetic information from the twins.”

It’s hard to know the long-term effects of He’s experiment. His genetic edits are heritable, which means they could be passed on by the girls and end up affecting future generations in ways that are impossible to predict. A scientific paper in 2016 found that decreased CCR5 function had improved the cognitive abilities of mice. Could He have ended up creating the world’s first humans with enhanced intelligence? “Six years ago, I didn’t notice this paper. I read this paper recently. When we did this trial our primary goal was immunity to HIV. We were not designing it for improving memory or intelligence. Are you asking whether the girls have better memory or intelligence?” Yes, I say. “Well, I’m not answering this question.”

On a personal level, I ask if he worries about the babies potentially developing diseases later in life because of the gene editing. He launches into an explanation about informed consent and commercial health insurance and tells me the parents are still very happy. It’s not really what I’m getting at. I say it must be strange not knowing if there will be problems in the future. “Oh, I tell you. A few years ago I said this: if those babies have a huge problem, I’m going to [commit] suicide.” Listening back to our conversation, I notice we’re both laughing as if he’s told a joke. Maybe that’s the only way to process something like this. “Please don’t kill yourself,” I hear myself say. He doesn’t make any promises.

For a man who lost almost everything, He has startlingly few regrets. I mention that before his experiment, he had been lauded in China. The Central Committee gave him a prestigious award as part of the Thousand Talents program. “I lost all my honors and positions in China,” he says. “But I get the honor from patients. That’s something new to me. There are thousands of patients, they think I could save them. I could help to defeat their diseases. So that’s a better honor. Honor from state, or honor from patients — I prefer honors from patients.”

He’s work is so controversial that at times it has put him in danger. Before he moved to Beijing, he says he was ambushed by a young man when leaving his office, who put him in a headlock and punched him twenty to thirty times. “I would say that there’s many people against me… All those people, they don’t want me to rise again. They don’t want me to work on gene editing.”

I wonder about his time in prison. Did it change him? “Well probably not. I don’t know if Martin Luther King was put in jail. Did it change anything for him? Or maybe Nelson Mandela was in jail for twenty-seven years. Did anything change for him?”

In 2017, He met James Watson, who discovered the shape of DNA. When I bring this up, He disappears off camera and cheerily returns carrying a huge oil painting of him and Watson. He says it depicts the moment he asked Watson what he thought about modifying embryos to make healthier babies. Watson is said to have replied: “Make people better.” This, He says, encouraged him to work on his gene-editing project.

As the oil painting suggests, He is deeply concerned about his legacy. Edward Jenner, the inventor of vaccines, and Robert Edwards, the IVF pioneer, are his idols, and he points out that both were criticized and even threatened in their day. “The good thing is that they didn’t give up. And after a few years, the world accepted and their technology was widely used… by millions of people. And of course, they are also remembered as heroes in science. They are my role models, and I hope I could be one of them.”

He is probably right that the technology he pioneered will soon be adopted more widely. In October, health regulators in South Africa appeared to open the door to the creation of genetically modified children. Meanwhile, a technique called “base editing” means there is a way to edit DNA that causes less damage than CRISPR. It may not be long before gene-edited babies become the norm.

He is optimistic that his work will create a better future: “In fifty years, children will be free of genetic disease because of gene editing before birth. So we will no longer see any muscular dystrophy disease or sickle-cell disease… The babies born will be healthy, and [gene editing] will be just as popular as the smartphone.”

Before our interview, He tweets out a slightly more alarming analogy: “Gene editing technology has the power to reshape the world, like nuclear bomb.” What could possibly go wrong?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply