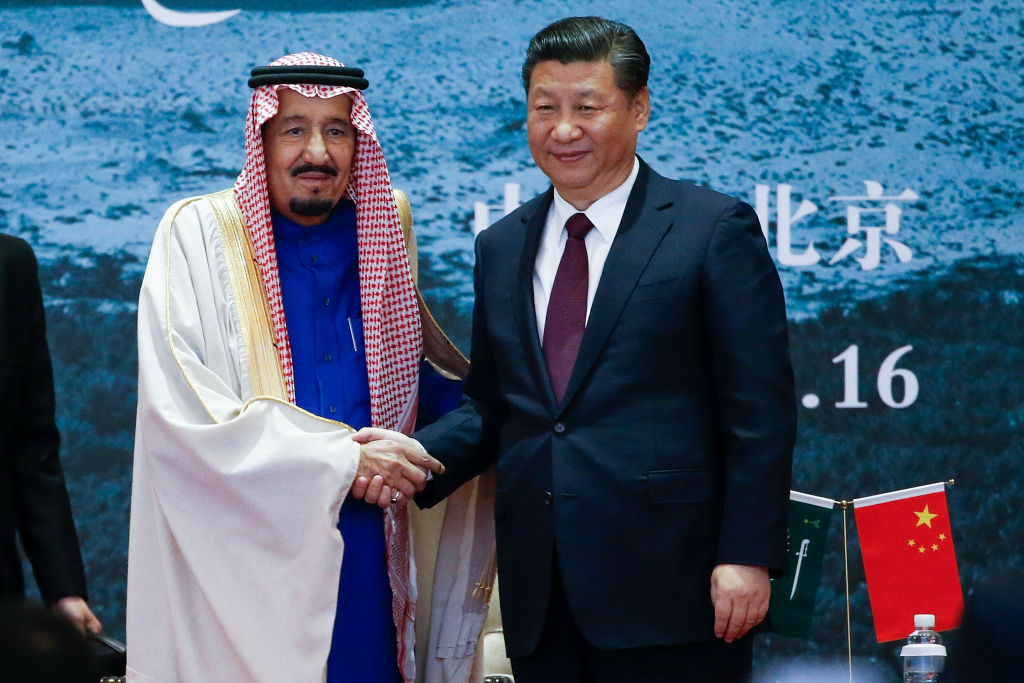

Joe Biden’s chickens are coming home to roost as Chinese President Xi Jinping visits Saudi Arabia. The trip itself has not been especially revolutionary. But it is another indication of America’s declining prowess in the region.

Xi was given a welcome befitting an ambitious leader (and notably different from how Biden was greeted in July). Beijing and Riyadh signed numerous economic agreements worth about $29 billion in total, including with Huawei, which will only further the Chinese technology giant’s control over global telecommunications infrastructure. Xi also advanced his desire to make the yuan a competitor to the dollar in the global economy, pushing for the use of the yuan in the oil trade with Saudi Arabia. Relations between China and Saudi Arabia were also upgraded to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.”

For decades, the United States has been the principal security provider in the Middle East. Since the Obama years, however, things have been slowly changing. There was the pivot to Asia, at the expense of American responsibilities elsewhere. The US left Iraq, only to have half of it fall to the Islamic State. Washington said it would intervene if Bashar al-Assad used chemical weapons in Syria, which he did, only for the US promptly changed its mind. America made a bad deal with Iran that gave Tehran new resources for its imperialist ambitions. And the US pulled out of Afghanistan, leaving the country under the control of the Taliban.

Biden also made it a cornerstone of his early foreign policy to re-enter the Iran nuclear deal, consequences be damned. The Gulf States and Israel were opposed, but the president showed no sign of changing course. Iran continued fomenting violence in Yemen and planned assassination attempts on US political figures like John Bolton and Mike Pompeo, but the administration stayed the course. Tehran began supplying arms to Russia for its war of conquest in Ukraine, but Biden kept negotiating. Only after mass protests and a violent crackdown in Iran, combined with the sheer intransigence of its leaders at the negotiating table, did Biden decide that maybe a deal is not going to happen.

Things were only made worse in the aftermath of the OPEC+ decision to cut oil output in November. Democratic members of Congress called for everything from stopping weapons sales to Saudi Arabia to pulling out American troops, and Biden, whose foreign policy helped to create the OPEC+ mess, did not shy away from joining the rhetorical frenzy. It is clear to anyone who watches American politics that the American left is no friend of the Gulf States.

Given all of this, it should not be surprising that the Saudis and others in the Middle East are broadening their options. America’s main strength in the region is its ability to provide security, so when that degrades, countries will be far more willing to partner with US foes. They will not abandon the United States altogether — that would be both unnecessary and costly — but they will seek to balance the influence of Washington with other forces, like China or Russia.

Speaking of Russia, the situation in the Middle East is slowly coming to resemble the situation in Central Asia, where the primary security provider (Russia) is not the same as the primary economic partner (China). As Moscow’s might in Central Asia collapses due to the war in Ukraine, those nations, too, are looking elsewhere — mainly to China. The consequence? Russia’s regional influence degrades.

The US is, of course, in nowhere near as dire a situation as Moscow is, but Washington’s mistakes are creating the conditions for similar results. China’s grand ambitions necessitate the destruction of the American global system, and they will exploit any and all opportunities.

The loss of America’s sway in the Middle East is not inevitable; it’s an unforced error. Simple steps, like ending the attempt to re-enter the Iran deal or responding with force whenever one of our Middle Eastern allies is targeted by Iran or its proxies, would go a long way.

It is also necessary to take a broader view than the Biden administration has. Human rights is an important part of American foreign policy, but it cannot be the predominating factor. The US can better influence human rights policy when it actually has influence over the country at issue, but if it alienates that country by spending more time condemning it than building a relationship, that influence will never materialize. If Saudi Arabia can counterbalance America with China, the impetus to reform is drastically reduced.

As Beijing’s influence slowly expands, the challenge for the US will get harder, not easier. It may not be possible for the Biden administration to turn things around with Saudi Arabia, as the relationship between the two leaders has become so toxic. But whether it be Biden or his successor, repairing relations with America’s Middle Eastern allies will need to be among the top foreign policy priorities. If China is difficult to deal with on its own, it will be even harder to manage if it has friends in the Middle East.