When Americans think about the word “whistleblower,” their minds may go to the 1970s, when Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein began communicating with the informant who came to be known as Deep Throat, after the pornographic film of the same name (their source, a disgruntled FBI official called Mark Felt, outed himself decades later).

But the history of whistleblowing in the United States predates Watergate by centuries.

“Whistleblowing in this country is not new,” says Jackie Garrick, executive director at the whistleblower-support group Whistleblowers of America.

She points to the case of Samuel Shaw, a Revolutionary War naval officer who witnessed the torture of British soldiers by Commodore Esek Hopkins of Rhode Island, the very first commander in chief of the Continental Navy. Shaw and a colleague named Richard Marven were dismissed from the Navy after they reported Hopkins’s misconduct. But the Continental Congress investigated Hopkins and suspended him from his position. Hopkins retaliated by filing a libel suit that led to Shaw and Marven’s arrest.

Their plight was brought to the attention of the Continental Congress, which passed America’s first whistleblower protection law in July 1778, establishing “that it is the duty of all persons in the service of the United States, as well as all other the inhabitants thereof, to give the earliest information to Congress or other proper authority of any misconduct, frauds or misdemeanors committed by any officers or persons in the service of these states, which may come to their knowledge.”

The Congress even paid for Marven and Shaw’s legal fees at a sum that is equivalent to around $50,000 today.

From those dissident sailors to the often tech-savvy and anonymous leakers who spill political, national security and financial secrets today, whistleblowing has often altered the course of American history, as well as the lives of those who are caught up in its currents.

My own brush with whistleblowers began when I was a reporter with the Intercept, an independent publication with a specialty focus on global affairs and the security state.

During the heat of the 2016 election campaign our DC newsroom started releasing leaks from a source calling itself “Guccifer 2.0,” which had penetrated the email accounts of a range of organizations and individuals close to the Democratic Party.

There was legitimately newsworthy content in the materials we published. For instance, one leaked email showed former secretary of state Colin Powell expressing relief that Brexit had distracted from an inquiry into the origins of the Iraq war. The world learned about the cozy behind-the-scenes relationship between the political press and the Hillary Clinton campaign — not a shock to anyone paying attention, but concrete evidence of how the sausage is made.

Although we didn’t know it at the time, it later became clear that Guccifer 2.0 and other hacks directed at the Democratic National Committee and Clinton campaign were the work of Russian intelligence.

Do I have any regrets about publishing stories containing “politically damaging quotes” from Clinton’s paid speeches to Goldman Sachs and others, obtained only due to the efforts of Russian hackers? Absolutely not. Newsworthy is newsworthy no matter its source, once vetted for accuracy of course. The stories I did — after vetting the authenticity of the material contained in these hacks — helped illuminate the inner workings of a political party that had, among other things, effectively crushed the Bernie Sanders-backed rebels in its midst, alienating millions of people in the process.

Newsworthiness aside, the Russian hacks revealed an uncomfortable new reality. Now, powerful nation-states were in the business of helping shape the news through illegal hacks and targeted leaks to reporters, often posing as do-gooder whistleblowers in the process.

And the Russians weren’t the only ones trying to control the international narrative in their own interests. In June 2017, our office received a massive trove of leaks from the email inbox of Yousef al-Otaiba, the United Arab Emirates’ ambassador to the United States and one of the most influential diplomats in the nation’s capital.

Those leaked emails helped produce all kinds of important stories — from the reality that the Emirates had secretly picked up the DC lobbying tab for the Egyptian government to a reckoning of the dollar figures flowing from the Gulf to certain DC think tanks (these articles probably helped push at least one of those think tanks to swear off Emirati funding.)

To this day I have no idea who hacked Otaiba’s inbox. Was it a disgruntled former employee à la Mark Felt? A human rights activist seeking to hold the Emirates accountable, like Samuel Shaw? More likely it was a rival state like Iran or Qatar, which was involved in a diplomatic crisis in the Gulf at that time.

Did I end up serving as a conduit for a foreign state’s agenda? I may never know, but the job of a journalist is to discern and expose the truth of what has happened, not to worry how the truth will be received.

It’s clear that this instantly sharable technology is changing the nature of whistleblowing, and not just because senior Democratic Party officials and enormously wealthy Gulf ambassadors, among others, seem to be unaware of two-factor authentication and basic information-security protocols.

While such high-profile hacks have caught the world’s attention, the internet is transforming the work of everyday whistleblowers, who can quickly spread the word about misdeeds and defend their reputations against the inevitable counterattack. James Gaddis is a single dad who worked at the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. He was asked to implement plans to create infrastructure for hotels, pickleball courts and golf courses at several state parks, but he thought they were unethical due to their lack of public review and decided to leak them. The public backlash spurred by the leak was so swift that the state’s Republican governor Ron DeSantis quickly squashed the plans.

The leak unsurprisingly cost Gaddis his job: although whistleblower protections at the state and federal level have gradually expanded over the years, they generally do not cover blowing the whistle over policy disagreements. “Almost all whistleblower laws are confined to essentially violations of laws and written procedures or rules,” confirms Stephen Kohn, a veteran whistleblower attorney.

But in today’s information environment Gaddis had an option that never existed for whistleblowers before him. He started a GoFundMe page. He had hoped to raise $10,000 to support himself and his daughter until he was able to secure gainful employment. He raised more than $200,000 in a matter of days.

“I have never loved the people of the State of Florida more than I do right now,” Gaddis told the local press. “I feel an overwhelming sense of thankfulness for the mind-boggling generosity of everyday folks of this state, and I will not let them down with the next steps I take. I will also ensure that I am transparent and accountable to the thousands of people that have helped me.”

But technological advancements are not always helpful to whistleblowers. They also create trails — virtual and literal — that make it easier for businesses and governments alike to pursue leakers. In 2017 a whistleblower named Reality Winner leaked intelligence about Russian interference in the 2016 election. Winner, who worked as an NSA contractor, was caught, tried and imprisoned partly due to watermarks that were visible on the documents she sent to the Intercept — they helped the government figure out exactly where the documents had been printed.

Attorneys like Kohn stress information security to the clients they work with. “The whistleblower’s got to be damn smart, let’s put it that way. And most of them have already left some form of footprint that could identify them before they even really know that they might become the target of a forensic search,” he says. Advocates like Garrick, a former whistleblower herself who reported conflicts of interest in DoD contracts, say that one of the biggest challenges they face is emotionally supporting people who choose to blow the whistle.

As anyone who’s worked in Washington can tell you, every staffer at a large organization has an interesting story to tell, from amusingly problematic behavior to moral turpitude to major breaches of the public trust. But most of them stay quiet because whistleblowers almost always face harsh judgment from their colleagues, career damage and sometimes public humiliation and legal repercussions.

“We have to take care of each other,” Garrick says, pointing to the story of a whistleblower who told her she had a gun and was thinking of killing herself.

“That made me think, no, we really need our own army. We need to fight back,” she adds.

So Whistleblowers of America is providing the country with something whistleblowers in the past never had: a community.

The organization frequently hosts online discussions where whistleblowers can receive support from their peers; they also help connect them with legal help and mental health support. Garrick also helps people put together and promote GoFundMes — which serves as a technological successor to the Continental Congress paying for Shaw and Marven’s legal bills.

They do all this with virtually no budget — Garrick works full time with no salary. There isn’t an armada of foundation and corporate donors lining up to fund an organization that supports people who blow the whistle on corrupt and unethical behavior.

And the way whistleblowers are received can vary. Julian Assange, for instance, was once a man of the anti-establishment left, bent on exposing the inner workings of the US empire. But his role in releasing Clinton campaign emails polarized public opinion the other way, with many on the right — including those who once championed his arrest — coming to see him as a heroic figure. In a polarized environment, whistleblowers themselves have incentives to choose sides.

Garrick’s only side, however, is that of the whistleblower.

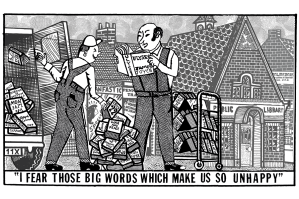

One of her latest projects is “Six Word Story.” Through many years working with whistleblowers, Garrick has seen all the words that have been used to degrade those who blow the whistle: rat, snitch, spy. So WoA is asking whistleblowers for six words they would use to describe themselves. “We’re trying to build this out and do this in a way where we can get people to share their words so that we can reduce the stigma,” she explains.

In a world where political parties and corporations and non-profits are as eager as ever to shut down internal criticism and potentially damaging leaks, the community support of organizations like WoA may make the difference between the public learning about unethical behavior or not.

Shaw and Marven had the Continental Congress at their backs; today’s whistleblowers could potentially have the whole world — one support-group call or GoFundMe at a time.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply