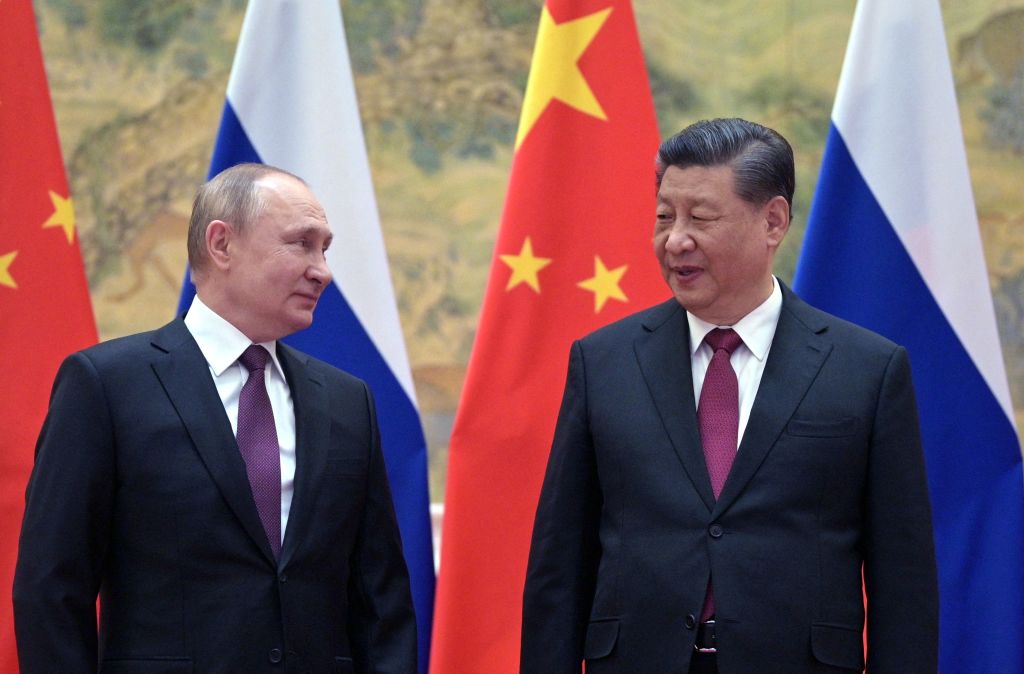

If Asia has entered the debate over the war in Ukraine, it is primarily through questions over the role China is purported to be playing in supporting Russia. Given the now-infamous declaration of a “partnership without limits” by Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping during the Beijing Olympics just weeks before the invasion, many observers have searched for signs of Chinese aid, military or economic, to Russia in the conflict. The scope of devastation in Ukraine and the probable war crimes being committed by Russian troops understandably mean less attention has been paid to how the conflict might affect geopolitical stability in the Indo-Pacific region. The exception is Taiwan — there has been considerable speculation over the influence of Ukraine on Beijing’s calculations there.

A flurry of early punditry proclaimed that the hesitant Western reaction to the Ukraine invasion would tempt Xi into moving on Taiwan sooner rather than later. Then, after Putin’s scorched-earth policy ground to a halt with large numbers of Russian casualties, other commentators confidently asserted that China’s timetable for invading Taiwan had been pushed back by five years or more.

But there is no reason to believe that the Ukraine invasion will have any effect whatsoever on Xi’s policy toward Taiwan. If there is indeed a timetable for invasion, it will proceed according to its own logic and not because of Russian success or failure in Europe. Not that Xi and the People’s Liberation Army leadership haven’t been watching the invasion closely. They will have noted the early confusion and irresolution in the West, the slow cobbling together of wide-ranging yet inconsistent responses, and the seeming disarray in Russia’s military strategy and operations. The likely result will be a more focused and lethal China, not one suddenly swayed either towards action or inaction because of events half a world away.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t real geopolitical consequences in the Indo-Pacific region from Russia’s aggression. Political alignments in the region are already shifting. Japan has long sought an entente with Russia, both to recover the Northern Territories taken in 1945 and to build a front against China. After the Ukraine invasion, however, Tokyo joined Washington and European capitals in laying strong sanctions on Moscow, clearly aligning itself with liberal nations. Geopolitics in northeast Asia are settling into two clear blocs, China-Russia versus Japan and the United States, with the Korean peninsula up for grabs.

Disturbing to both Washington and Tokyo has been India’s move to buy oil from Russia while abstaining from a UN condemnation of Moscow’s aggression. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s actions have undercut the solidarity of the Quad security grouping and raised questions as to how effective the group — India, Australia, Japan and the United States — can remain going forward. Though it’s unlikely that New Delhi would suddenly draw closer to Beijing, a weaker Quad might, for example, encourage Moscow to try brokering eased tensions between India and China, the more to complicate Washington and Tokyo’s strategy.

Given the West’s inability either to prevent the invasion of Ukraine or robustly oppose it, there may be spillover effects among smaller Asian nations maneuvering for patronage. The tarnishing of the liberal community’s authority could result in a subtle shift toward China. That may explain the recent decision by the Solomon Islands to sign a security agreement with Beijing, while a strengthening of ties between China and the Mekong Basin states is likely. The Philippines might get closer to China if the front-runner in May’s presidential election, Bongbong Marcos, son of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos and head of current president Rodrigo Duterte’s party, wins.

The Ukraine war could also lead to geoeconomic shifts, as China creates alternatives to financial systems in the West and Russia becomes dependent on China’s grain and energy import needs, while India moves to tie itself to Russia’s energy sources at the same time it fills the wheat-export shortfall from Ukraine.At the macroeconomic level, however, all of Asia will suffer from higher costs for everything from energy to commodities, stoking inflation and depressing economic growth. That, in turn, will put domestic pressure on many regional governments, some of which are democracies struggling to remain liberal. Others are willing to turn to China for easy loans and other aid. No one should have confidence that America is ready for this new era of geopolitical confusion and conflict. A mixture of fatalism (“Afghanistan was a disaster and Biden doesn’t know what he’s saying”) and unrealistic self-satisfaction (“the war in Ukraine is revitalizing the liberal world order”) presently dominates elite salons in Washington.

America’s elites are for the most part both inexperienced in power politics and mentally unprepared to deal with a genuinely unstable world. The disorder spreading across borders, including America’s, rarely reaches their professional or personal precincts. It is possible that China will indeed take advantage of a distracted and unprepared Washington to continue extending its control over disputed maritime territories, while ratcheting up pressure on Taiwan and other countries and supporting other disruptive actors. An Asia swept up in whirlwinds of turmoil would be an even greater geopolitical challenge than Russia’s horrific destruction of Ukraine.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.