Problems about the misuse of history, especially on subjects such as race and colonialism, have been running for a long time.

But when it comes to the ancient world, there are also problems about the misuse of literature.

Dame Mary Beard’s “manifesto” Women and Power (2018) contains an example of the problem. Her thesis is that women’s voices in the public sphere (my emphasis) have been “silenced” by men ever since the West’s first literature (Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey) gave us our first access to “Western” thoughts, deeds, beliefs, hopes and fears (c. 700 BC).

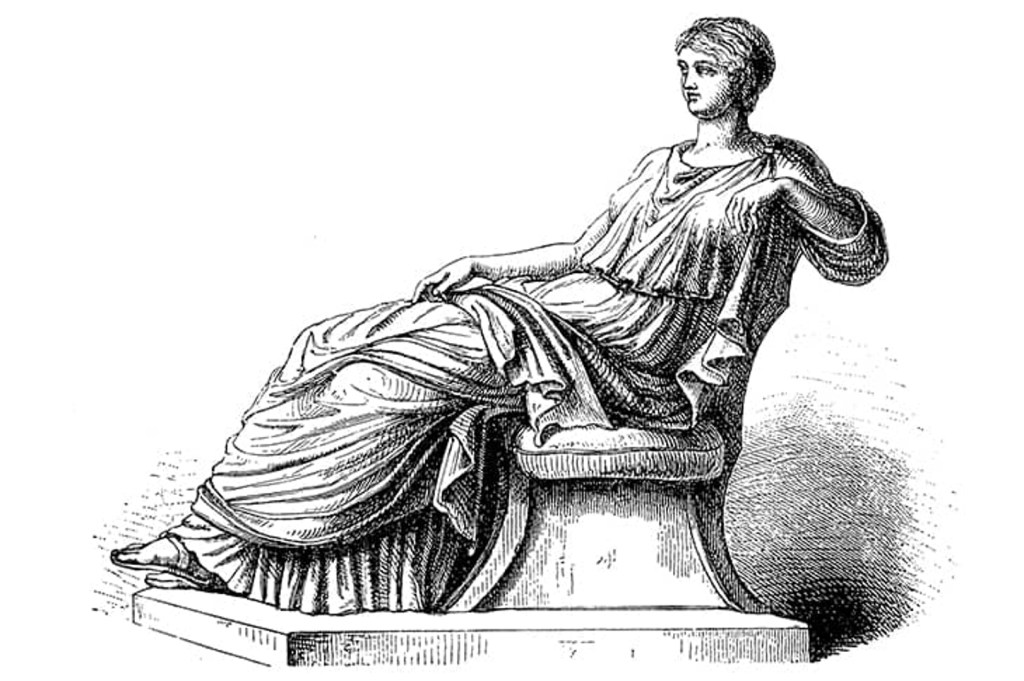

The problem exists in the first example of her thesis, to which she returns four times — Penelope, the wife of Odysseus. During Odysseus’s twenty-year absence at Troy, she had been left to run the home and the estate and raise their son Telemachus (Telemachus was now twenty); and for the last four years, she had been besieged by 108 suitors who, reasonably assuming Odysseus was dead, were seeking her hand in marriage. A woman under pressure, then.

That is the situation when the Odyssey begins, and in the first book, while the suitors are munching their way through Odysseus’ livestock over dinner, Penelope descends from her bedroom and orders Telemachus to stop the bard Phemius from singing what is to her a painful song about the Trojan War. Rejecting her request, he orders her back to her bedroom. She is “surprised,” “takes his words to heart” and retires. Dame Mary concludes that here, from the very beginnings of Western literature, we have a precise example of the thesis she is proposing.

But is it? This is Penelope’s home, not the “public sphere”; she wishes to change her son’s choice of music and is refused; and though surprised (the first time this has happened?) she takes his words seriously. This is a mother-and-son disagreement.

More broadly throughout the Odyssey, far from being “silenced,” Penelope engages sympathetically with her son, who (as the poet makes clear) is attempting to grow into his destined position of family head. In the eyes of the suitors, Penelope is a really tough nut; she stands up to them and they admire her trick to delay her marriage (claiming to be weaving a shroud for Odysseus’ father). Even after the disguised Odysseus has killed them, she will not be harried by Telemachus into recognizing him, except on her own terms. When it comes to direct speech too, no one but Odysseus and Telemachus speaks more than she does. Some “silence!” It may not be irrelevant that in the Iliad too, there is no “silencing” of women either.

None of this affects Dame Mary’s overall thesis, but it does give a skewed picture of Penelope. By contrast, Margaret Atwood’s Penelopiad goes the whole hog: she makes a nonsense of the epic by openly reworking it to turn Penelope and her (in Homer) treacherous maids into twenty-first-century “silenced” feminist icons. Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls plays the same sort of game with the Iliad. At any moment one expects the soldiers to spray each other with lager.

The contrast with Tom Stoppard’s new film, an effortlessly artful and artless prose-poem told by the shade of Penelope, is acute. It tracks the story of the Odyssey. Its language is in tune with Homer’s, e.g. the repetitions (note “bloody-fingered” rather than “rosy-fingered” dawn); so are the deities. At the same time it provides new angles on the Homeric version: the wicked woman for Penelope is not Clytemnestra (as it is for Homer) but her cousin Helen, who started the whole Trojan war (“Miss World… though her wake was red with Greek and Trojan blood”) and of whose beauty she is bitterly resentful. She wonders where to lay her curse for her name “stamped on the pattern for long-suffering stay-at-home faithful wives busy at the loom.” In a heart-stopping moment she contrasts Helen with herself, “the homespun daughter of King Icarius.” There are intentional anachronisms. One could say much more.

Far from imposing himself on the Odyssey, Stoppard has worked with the grain of the epic and drawn inspiration from it. Anyone who reads the Odyssey as a result of this film would find themselves not utterly lost but immediately engaged in a story that has thrilled millions for 2,700 years.

Tom Stoppard’s Penelope (Hat Trick Productions) is available online. Search “Classics for All Penelope” for tickets. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2022 World edition.